Study warns of delayed flu outbreaks after pandemic ends

Credit: Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

- A new study out of Princeton suggests that measures to prevent COVID-19 are also preventing certain other diseases.

- The nature of seasonal diseases means that people who avoid them this year may just be putting it off, leading to a large wave later.

- These estimates don’t mean we should be less preventive now, only that we must be sure to take care in the future.

As the United States continues to struggle with the pandemic, the proven effectiveness of face masks to reduce the rate and risk of infection continues to be underutilized. Places that have implemented mask and distancing mandates are seeing generally lower rates of transmission and infection than those without these mandates, as more fully explained here, here, and here.

However, one of the three iron laws of the cosmos is the law of unintended consequences; no matter what you do, there will be at least one.

As a study out of Princeton has just shown, this also applies to live-saving mask mandates. Given that many other diseases follow predictable cycles, a team of researchers has shown that the steps we’re taking to prevent the spread of COVID-19 now may lead to larger outbreaks of seasonal diseases later.

Before we go any further, we want to make it clear that we are not telling you stop wearing a mask, social distancing, or taking all the precautions against catching and spreading COVID. The point of this study and this article is to make people aware of a side effect of these measures so that we can better deal with them later, not to suggest that these measures not be taken.

A team of researchers based out of Princeton published a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences showing the predictions of a model that estimates the after effects of our current efforts to avoid COVID-19.

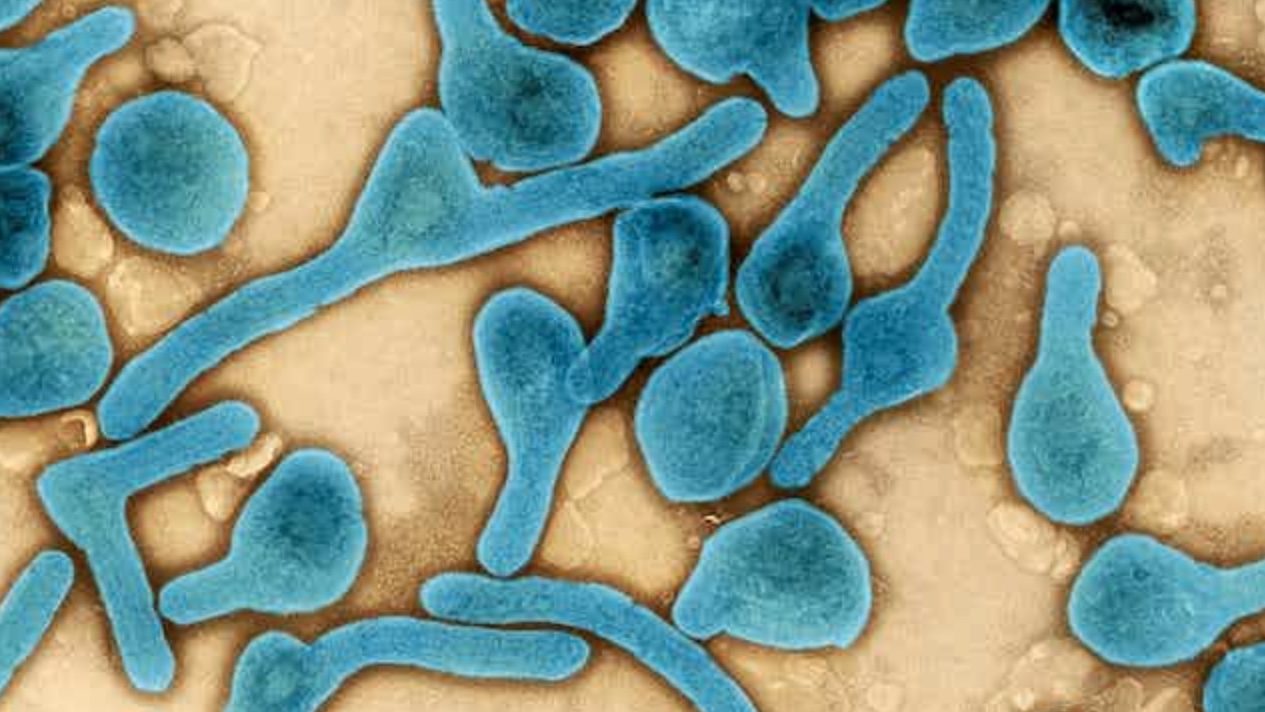

As it turns out, Non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as social distancing and wearing masks help prevent more than just COVID-19. Instances of other diseases, such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and the flu, are also lower than they would otherwise be due to people taking these precautions. Cases of RSV may have declined by as much as a 20 percent already.

This makes a lot of intuitive sense. Your mask doesn’t care what kind of virus it keeps you from exhaling towards other people; it stops all of them. If you stay inside to avoid catching a particular disease, you still avoid all of them. This kind of thing has happened before. The precautions taken during the 1918 flu pandemic probably reduced measles cases by a third.

However, these diseases come back seasonally and will be there waiting for us when the current pandemic ends. This might be a bit of a problem, as lead author Rachel Baker explained:

“While this reduction in cases could be interpreted as a positive side effect of COVID-19 prevention, the reality is much more complex. Our results suggest that susceptibility to these other diseases, such as RSV and flu, could increase while NPIs are in place, resulting in large outbreaks when they begin circulating again.”

Think of it like this: As fewer and fewer people get these diseases due to our current mask and social distancing tendencies, fewer and fewer people have immunity to them. Immunity to RSV lasts only a few years. If people who would have gotten it this year don’t, they may contract and spread it next year when they aren’t working so hard to avoid respiratory infections, along with all the other people who were likely to get it next year anyway for typical reasons.

The model is less exact for the flu, given the number of variables affecting how contagious the flu is from year to year, but a similar principle applies.

There is a fair amount of uncertainty to these findings, as the authors admit. Outbreaks in some areas have been better studied than others. The behavior of these seasonal outbreaks is more thoroughly understood in Florida than in Minnesota, for example, and these predictions may not be as applicable there. The models are also highly dependent on what measures we take and when to fight COVID-19, and the worst-case ones rely on a lot of things happening in tandem.

So while we can’t know exactly what that next flu season will look like, the essential finding of this study is that it is likely to be worse than it otherwise would be, everything else being equal. Various measures, such as getting more people vaccinated against the flu and keeping people home when they are sick with seemingly banal colds, will be necessary in the years to come. Hospitals should also brace for higher than average numbers of people coming in as a result of this.

A chart from another study on the effectiveness of masks and lockdowns. The grey line in the bottom two marks when mask mandates were imposed. Credit: Zhang, Li, Zhang, and Molina

Again, before you decide that this means mask mandates are just delaying some kind of reckoning, we can look at the numbers. Several sources agree that the coronavirus is deadlier than the flu. We also don’t have a vaccine for it yet, unlike for the flu, and keeping yourself and others from getting sick now remains extremely important for keeping people alive.

A friend of mine remarked at the beginning of the pandemic that certain events in society leave marks on the people in it, much like growth rings on a tree showing years of drought decades after it occurred. If the findings of this study are accurate, then COVID-19 will leave rings visible in seasonal outbreaks over the next few years alongside the slew of others it will create.

Given what this study shows us and the hard-learned lessons we have about what happens when you don’t listen to scientists, maybe we’ll do a better job at controlling those potential epidemics.