Cancer cells hibernate to survive chemotherapy, finds study

Credit: Adobe Stock

- Cancer cells go into a state similar to hibernation when attacked by chemotherapy.

- The low-energy state is similar to diapause—the embryonic survival strategy of over a 100 species of mammals.

- Researchers hope to use these findings to develop new cancer-fighting therapies.

When attacked by chemotherapy, all cancer cells have the ability to start hibernating in order to wait out the threat, finds new research. The cancer cells hijack an evolutionary survival mechanism to transition into a state of “rest” until chemotherapy stops. Devising therapies to target the cells in this slow-dividing state can prevent the cancer from regrowing.

The discovery was made by Dr. Catherine O’Brien and the team from the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre in Canada. Professor O’Brien, who teaches in the Department of Surgery at the University of Toronto, described that the tumor acts “like a whole organism, able to go into a slow-dividing state, conserving energy to help it survive.”

She compared this to animals who enter hibernation to get through difficult environmental conditions. Dr. Aaron Schimmer, Director of the Research Institute and Senior Scientist at the Princess Margaret, was even more specific, sharing that the behavior of the cells was akin to that of “bears in winter.”

“We never actually knew that cancer cells were like hibernating bears,” explained Schimmer. “This study also tells us how to target these sleeping bears so they don’t hibernate and wake up to come back later, unexpectedly.”

He thinks this adaptation by the cells can be the key cause of resistance to drugs.

Cancer cells may go to into diapause, entering a drug-tolerant persister (DTP) state.Credit: Cell

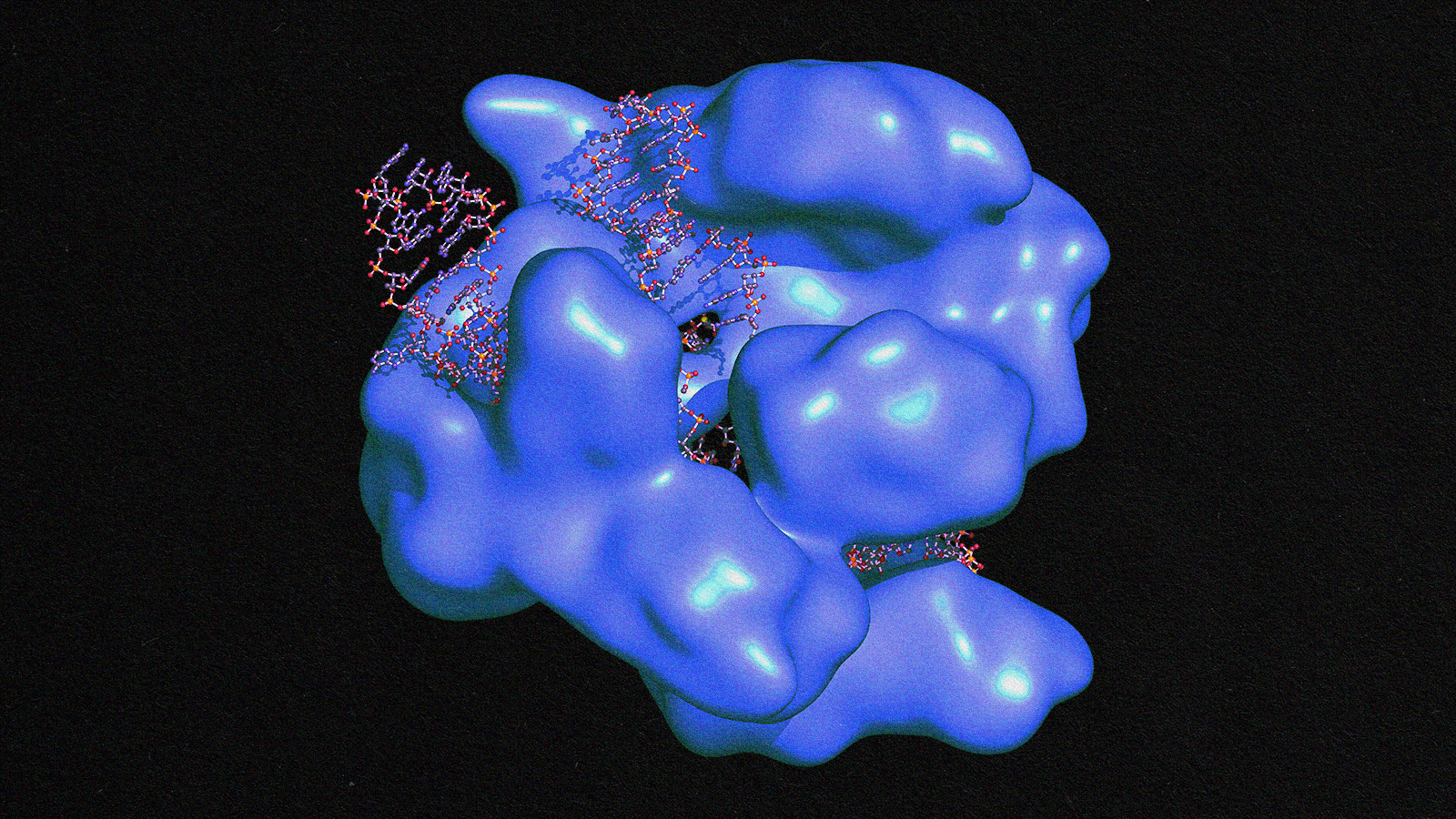

The scientists arrived at their observations by observing human colorectal cancer cells, which were treated with chemotherapy in a petri dish. This caused the cells to go into a slow-dividing state during which they ceased expanding and needed little nutrition. Such a reaction continued as long as chemotherapy was present.

The low-energy state of the cells was similar to diapause—the embryonic survival strategy of over a 100 species of mammals. They protect embryos by keeping them inside their bodies during extreme situations of very high or very low temperatures, or when sustenance is not available. Minimal cell division takes place when animals are in this state, while their metabolism slows to a crawl.

“The cancer cells are able to hijack this evolutionarily conserved survival strategy, even as it seems to be lost to humans,” pointed out Dr. O’Brien.

When the cells are in this state, they activate a cellular process known as autophagy (means “self-devouring”). While this is taking place, and if no other nutrients are present, the cell feeds on its own proteins and other cellular parts to survive. Observing that, the scientists tried impeding autophagy and found that the cancer cells were destroyed, succumbing to chemotherapy. Knowing this can lead to new therapies, according to O’Brien, who proposed that “We need to target cancer cells while they are in this slow-cycling, vulnerable state before they acquire the genetic mutations that drive drug-resistance.”

Check out the new study published in Cell.