Which country is the best place to die?

- Researchers conducted an international survey to determine what constitutes good end-of-life care and which countries are the best at providing it.

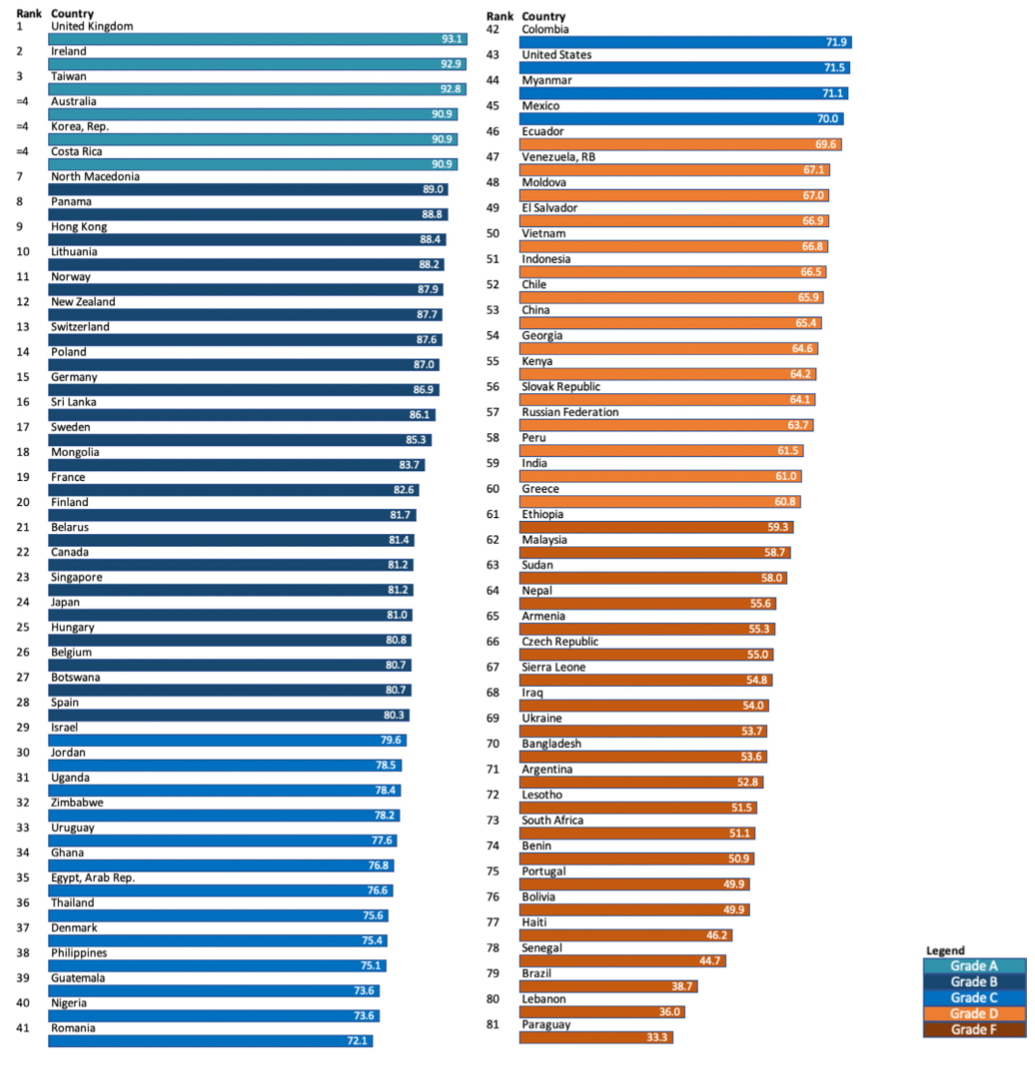

- They scored 81 countries, most of which earned a grade of “C” or below for their palliative care. The United Kingdom ranked first. The U.S. ranked 43rd.

- Higher income, universal health coverage, and wide availability of opioids for pain relief were generally associated with better scores.

Death is an inevitable part of life — a mysterious climax that all humans face, evoking wonder and trepidation. That’s why dependable end-of-life care is so vital. While only some of us break bones, develop cancer, or catch an infectious disease, we all die eventually. To depart with dignity in relative comfort shouldn’t be a rare privilege.

Regretfully, new research published in the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management shows that many countries do not offer their citizens a good death.

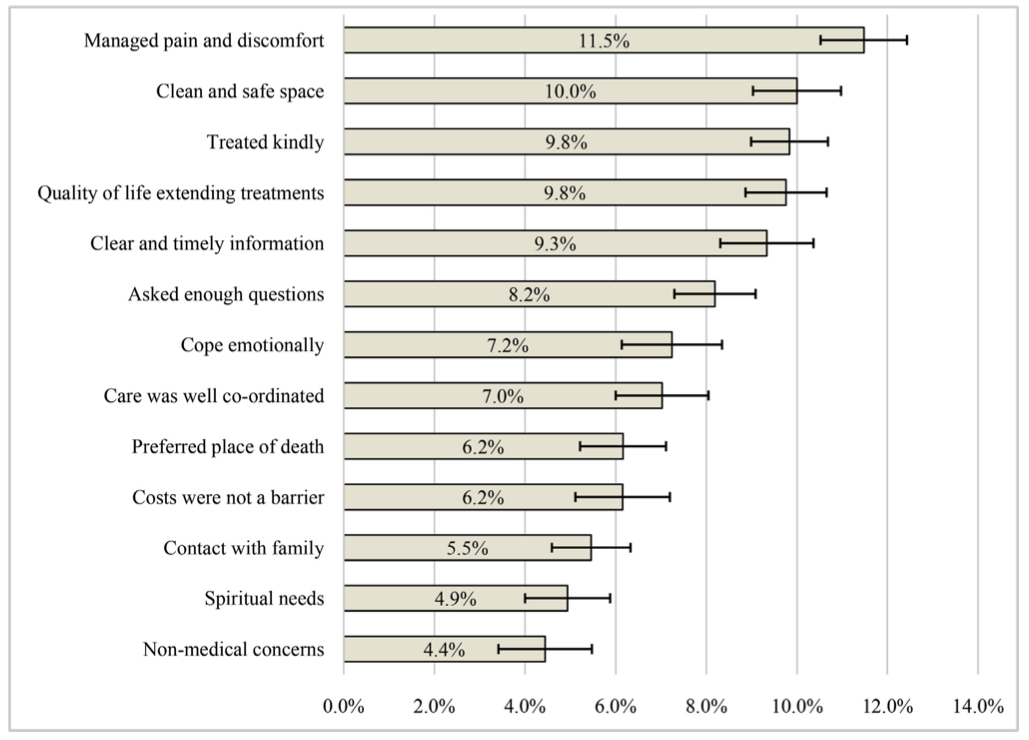

Eric Finkelstein — a professor of health services at the Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore, and the Executive Director of the Lien Centre for Palliative Care — led an international team of researchers to conduct a sweeping analysis of countries’ end-of-life (palliative) care. Finkelstein and his colleagues first set out to characterize quality end-of-life care, reviewing 309 scientific articles to determine the factors involved. A few that they identified included:

- The places where health care providers treated patients were clean, safe, and comfortable.

- Health care providers controlled pain and discomfort to patient’s desired levels.

- Health care providers provided appropriate levels and quality of life extending treatments.

- Costs were not a barrier to a patient getting appropriate care.

The researchers settled on 13 factors in total. They then surveyed 1,250 family caregivers across five different countries who had recently looked after a now-deceased loved one to ascertain the relative importance of each indicator. Here’s how the factors ranked:

Finally, the researchers sought out hundreds of experts from 161 countries to rank their respective country’s end-of-life care based on these weighted factors, asking them to “strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, or strongly agree” with whether their country’s healthcare system generally met each palliative need. To be eligible, experts had to be “either 1) a representative of the national in-country hospice-palliative care association or similar national professional association with an established leadership role, 2) a health care provider (physician, nurse) involved in provision of palliative care, or 3) a government employee or academic with knowledge of palliative care in the country.”

At least two experts were required to respond from a specific country for the researchers to consider the nation’s score valid. In all, 81 countries comprising 81% of the world’s population ended up being ranked.

The United Kingdom earned the highest score in the study, followed closely by Ireland, Taiwan, Australia, South Korea, and Costa Rica. These were the only countries to earn an “A” grade, scoring 90 or above. Ukraine, Argentina, South Africa, and Lebanon were a few of the 21 countries to merit an “F” grade, scoring 60 or below.

Finkelstein found the results disheartening.

“Many individuals in both the developed and developing world die very badly – not at their place of choice, without dignity, or compassion, with a limited understanding about their illness, after spending down much of their savings, and often with regret about their course of treatment,” he said in a statement.

Higher income, universal health coverage, and wide availability of opioids for pain relief were generally associated with better scores.

Of note, the United States earned a “C”, ranking 43rd of the 81 countries with a middling score of 71.5. Commenting on why the U.S. ranked so poorly, especially compared to other high-income countries, Finkelstein said that Americans often spend tons of money on excessive, often futile treatments and surgeries aiming to extend life at the dusk of one’s existence — sometimes just for weeks or months — rather than focusing on ensuring quality of life at the end.

A key drawback of the study is that each country’s ranking was determined by an average of only two experts. While the researchers made clear that these experts are quite knowledgeable and respected, it seems hardly fair to rate an entire country’s end-of-life care system based on the opinions of just two individuals, each of whom is undoubtedly biased by their own experiences.

The experts were also asked for their thoughts on what facilitates good end of-life-care in a country. Collectively, they suggested that investment from the national government, patient-centered, integrative care, and universal healthcare with free access to palliative care services contributed greatly.