A surprisingly strong link between altitude and suicide in the U.S.

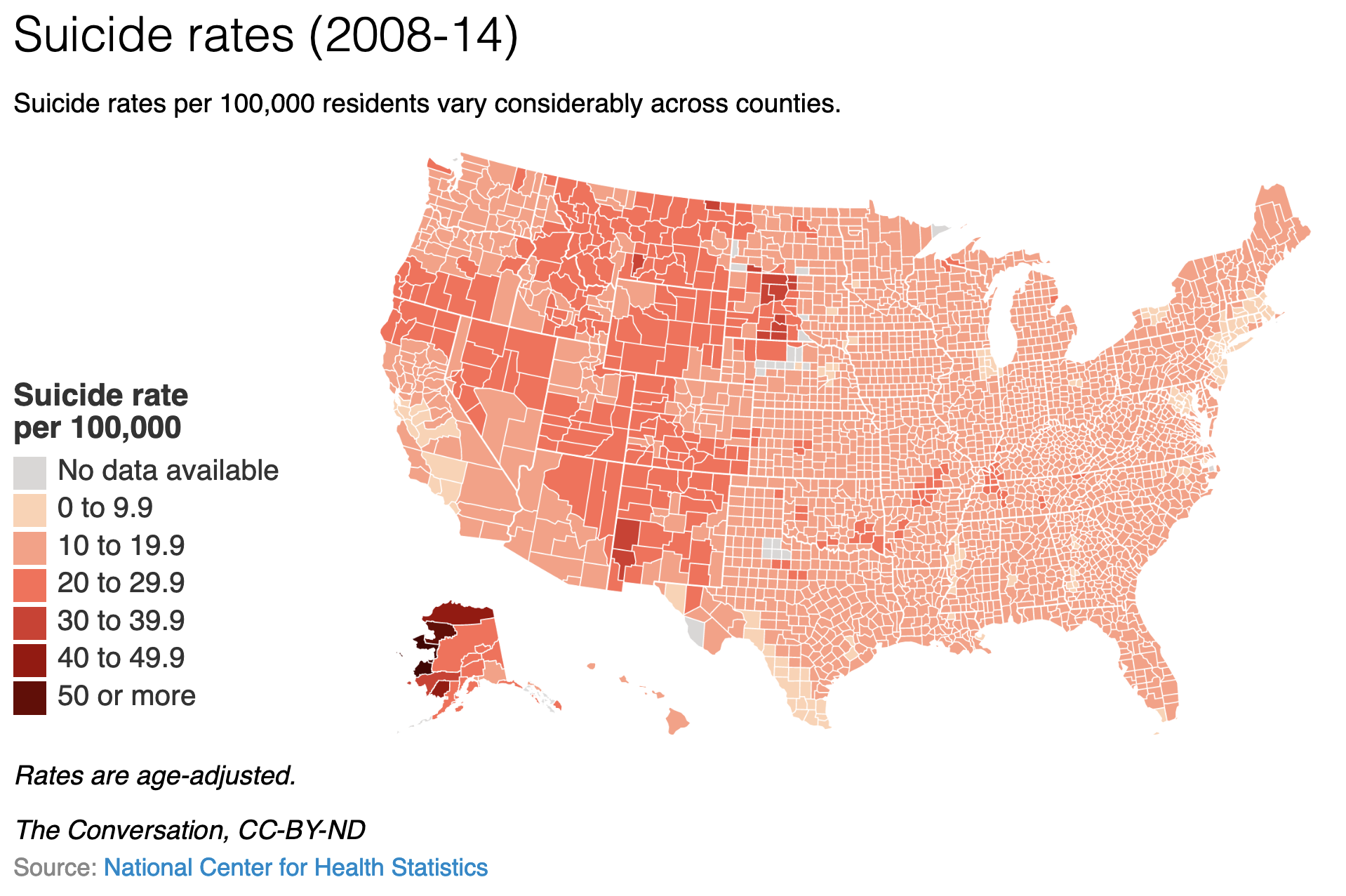

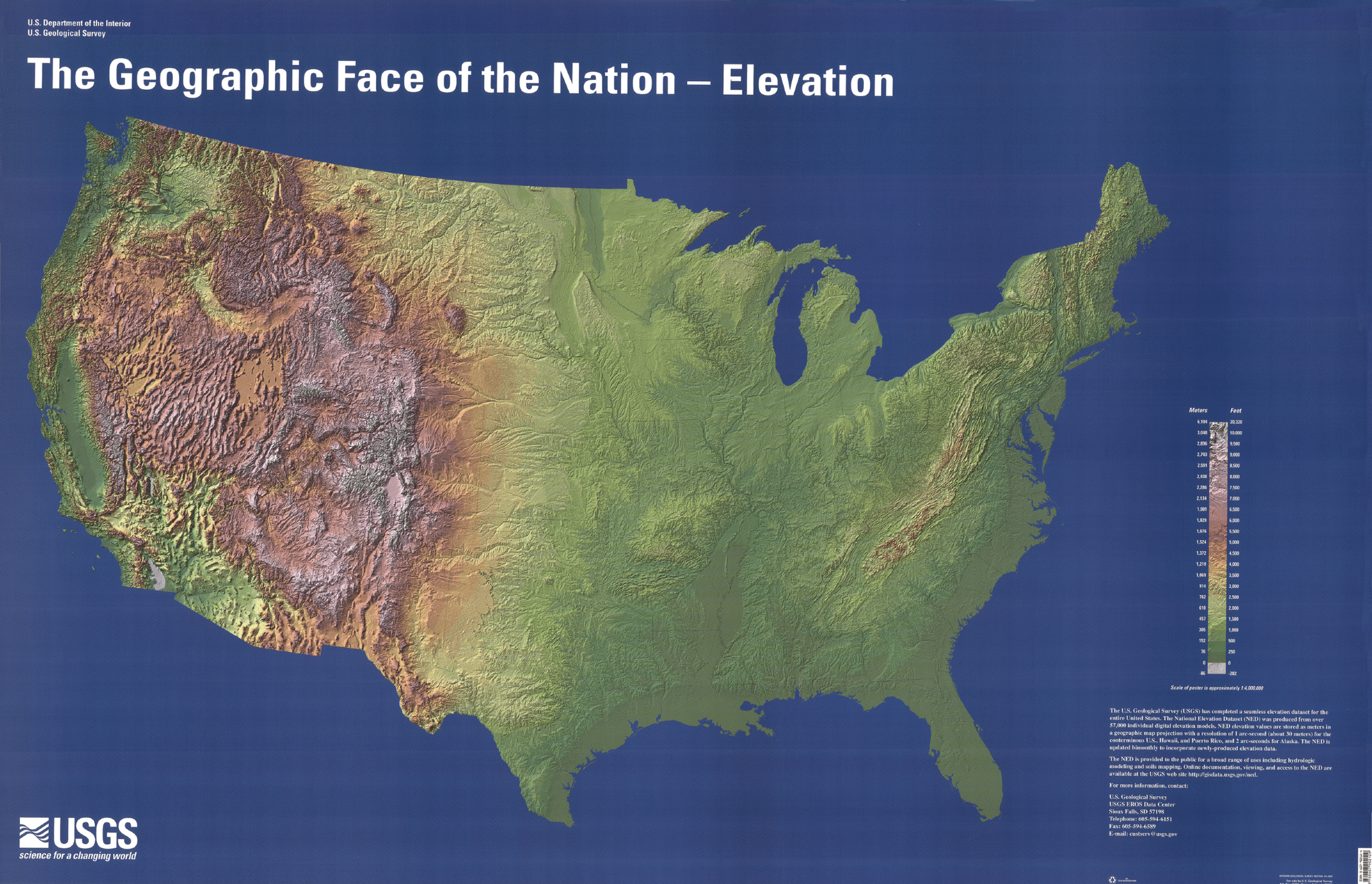

- Over the past two decades, researchers have observed that people living at higher altitudes have an increased risk of suicide. For every increase of 100 meters, suicide rates rise by 0.4 per 100,000 people.

- One explanation is that lower oxygen levels in the air interfere with brain activity.

- On the whole, living at higher altitudes reduces all-cause mortality. The reduction in cardiovascular disease and cancer outweighs elevated suicide rates.

You may have heard about the benefits of living at higher altitudes. Available evidence suggests that inhabitants enjoy reduced mortality from cardiovascular diseases, stroke, and certain types of cancer, as the body is forced to adapt to a life with less oxygen.

But dwelling at higher elevations may be a double-edged sword. As strong as the evidence is for altitude’s physical benefits, there’s equally impressive data showing that living at higher altitudes has mental costs, particularly an increased risk of suicide. In a systematic review published in May, researchers pored over all available published studies on the topic. Of the 19 studies conducted, 17 found a link between higher altitude and suicide.

In one, Hoehun Ha, an assistant professor of geography at Auburn University at Montgomery, and his colleagues compared U.S. suicide rates at the county level with the average altitude in each county. Since suicide is heavily affected by a multitude of variables, they also controlled for socioeconomic and demographic factors, such as unemployment rate, rates of substance abuse, ethnicity, and the ratio of population to primary care physicians.

“We found that, for every increase of 100 meters in altitude, suicide rates increase by 0.4 per 100,000,” he wrote.

Another study published just this month examined the association between altitude and suicide rates in American veterans. Critically, the researchers behind it controlled for population density, among a variety of other potential confounders. Higher altitude areas are often more sparsely populated, so perhaps loneliness is what’s leading to higher suicide rates, not elevation. But even when factoring in population density, they found a strong correlation between altitude and suicide.

“We also analyzed the 50 counties with the highest suicide rates and the 50 counties with the lowest suicide rates for the U.S. veterans population and found that there was a 3-fold difference in the mean altitude between these two groups of counties,” they added.

Given that the link between altitude and suicide has been so thoroughly vetted, researchers’ next task is to explain it. They have focused on one leading hypothesis: hypoxia. Oxygen concentrations are lower at higher altitudes, meaning that the blood might not be able to deliver enough of the life-essential element to the body’s tissues, particularly the brain. While organs like the heart and lungs appear to adapt to this dearth over time, the brain may not be so amenable.

Experiments in animals have demonstrated that chronic hypoxic conditions decrease the production of serotonin in the brain. For a long time, it was thought that reduced levels of serotonin are linked to depression, though that finding now has been cast into serious doubt. Still, it is reasonable to hypothesize that reduced oxygen levels interfere with brain activity, possibly in a nefarious way.

Despite the link between altitude and suicide, on the whole, living at higher altitudes reduces all-cause mortality. The reduction in cardiovascular disease and cancer outweighs elevated suicide rates. That is good news for anyone pondering a move to the Mountain West.