A cancer immunotherapy technique may prevent diabetes

Credit: GERARD JULIEN via Getty Images

This article was originally published on our sister site, Freethink.

Nearly 2 million Americans suffer from type 1 diabetes — a condition that causes drastic spikes or drops in sugar levels and, in turn, dizziness, nausea, and fatigue. It’s a condition that must constantly be monitored, something that a lot of diabetics find mentally exhausting.

One diabetic, Naomi, told the BBC that she couldn’t handle “the physical or mental challenges of diabetes anymore,” and struggled to monitor her blood sugar levels multiple times a day. Naomi’s struggle isn’t unique — it’s called diabetes burnout.

There’s no cure for type 1 diabetes. However, researchers at the University of Arizona have adapted a cancer immunotherapy technique that has produced promising results in treating diabetes (in mice). The researchers engineered immune cells to fight off rogue T cells (immune cells that go haywire and attack the body) that can damage the pancreas, causing type 1 diabetes.

This new technique would prevent that from happening — and if it works in humans, it could be an exciting first step for diabetics like Naomi.

T cells and diabetes

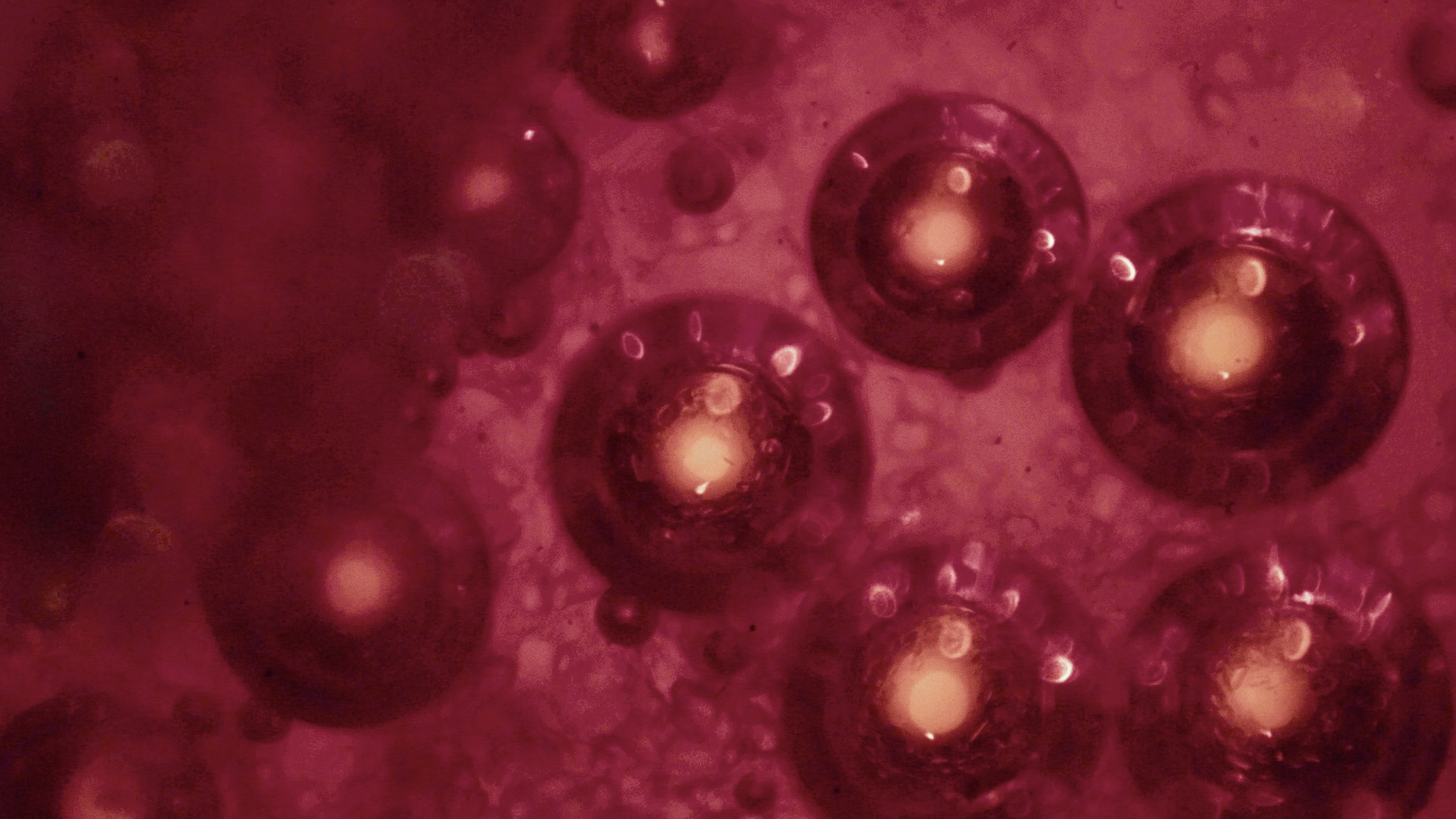

Type 1 diabetes is a kind of autoimmune disorder, which is hypothesized to occur when rogue T cells attack the pancreas’s insulin-producing beta cells. As a result, a patient with type 1 diabetes is unable to regulate their blood sugar levels effectively.

Patients must take artificial insulin daily to avoid all this. If they don’t, they run the risk of amputation, coma, or even death.

To prevent the development of this disease, scientists behind the new research, published this November in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, planned to stop the attack at its source — the rogue, pathogenic T cell.

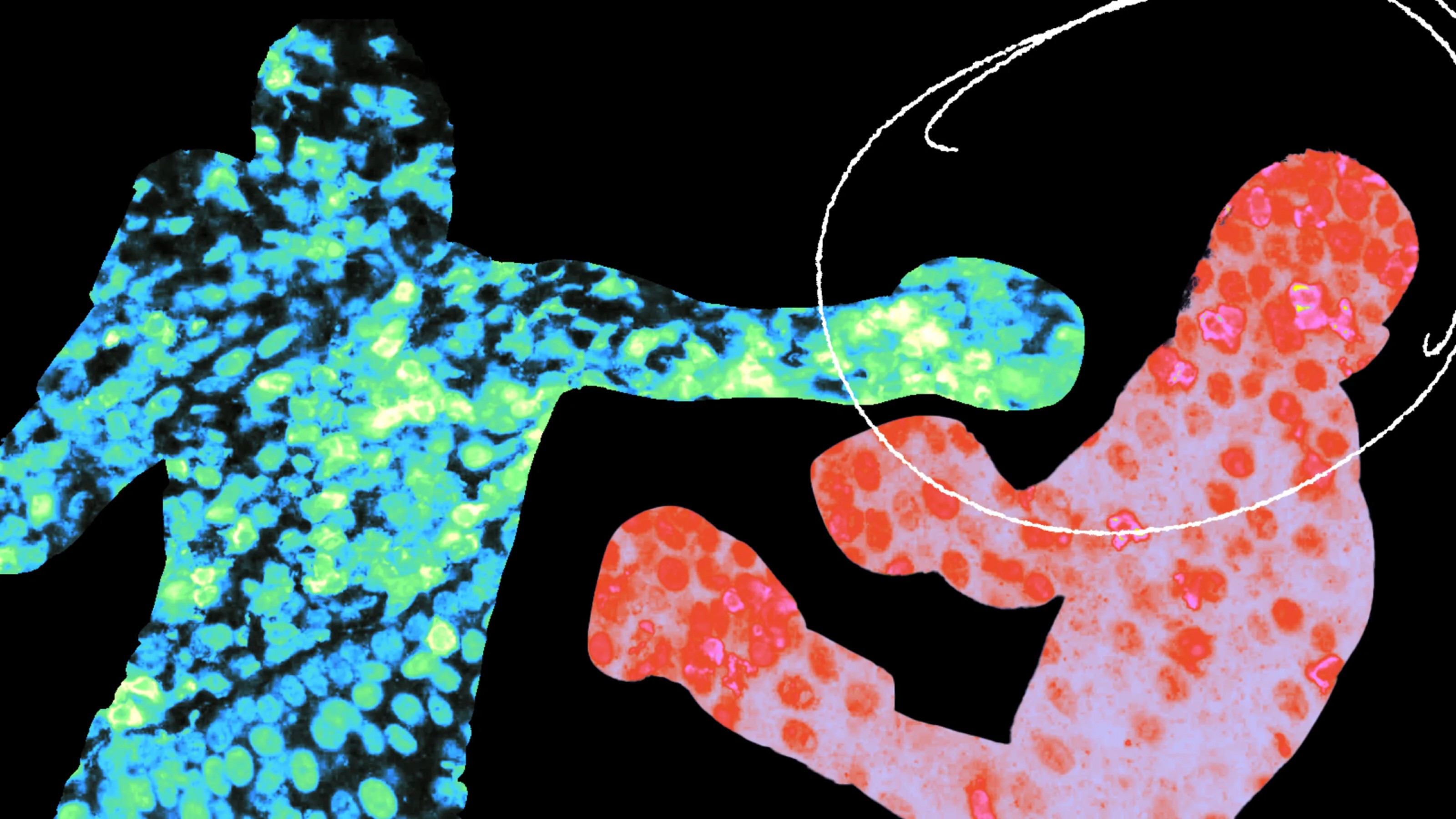

The research team bioengineered a T cell that looks and behaves just like the rogue T cell they’re trying to eliminate, which they named 5MCAR.

This bioengineered T cell can target and kill the pathogenic T cells on its own or order natural T cells to do it. Both approaches are designed to prevent healthy pancreas cells from being attacked.

Michael Kuhns, the study’s lead author and an associate professor of immunobiology at the University of Arizona, says that this design was a way to take advantage of evolution’s natural process instead of reinventing the wheel.

“We engineered a 5MCAR that would direct killer T cells to target autoimmune T cells that mediate type 1 diabetes. So now, a killer T cell will actually recognize another T cell. We flipped T cell-mediated immunity on its head,” said Kuhns.

Essentially, the idea is that the engineered T cells would target the rogue T cells and turn the rest of the immune system against them, too — thus, stopping the damage that causes type 1 diabetes.

The results

To see how well this worked in practice, researchers tested their engineered T cells in a rodent model of type 1 diabetes and found that the engineered T cells were incredibly effective at finding and attacking rogue T cells.

“When we saw that the 5MCAR T cells completely eliminated the harmful T cells that invaded the pancreas, we were blown away,” says Thomas Serwold, co-author of the study and assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School.

“It was like they hunted them down. That ability is why we think that 5MCAR T cells have tremendous potential for treating diseases like type 1 diabetes.”

The human question

Of course, success in mice models does not necessarily mean that this treatment will be effective in humans. Similar CAR T cell therapies have been approved by the FDA to treat blood cancers, but while they have shown early success, there have also been several deaths during clinical trials.

All and all, targeted T cell therapies may have a promising future for fighting these diseases and disorders, but further research will need to be done before these can confidently and effectively be brought to humans.