Japanese researchers hope to launch a satellite made of wood in 2023

Credit: Rumman Amin via Unsplash/Peter Jurik via Adobe Stock/Big Think

- Orbiting around Earth are hundreds of thousands of bits of space debris.

- Some of this stuff comes plummeting down eventually, but not enough of it.

- Wood satellites would burn up in the atmosphere without falling on anyone or anything.

It makes sense that this idea comes from the country that brought us origami, those lovely and often diabolically complicated artworks of folded paper. With Earth now surrounded by an orbiting junkyard of satellites, scientists at Kyoto University and Sumitomo Forestry in Japan have proposed a surprising solution: satellites made of wood.

Credit: JohanSwanepoel/Adobe Stock

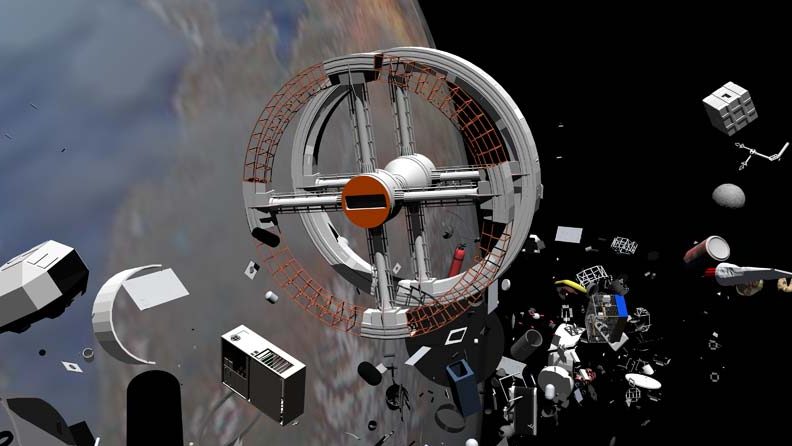

NASA is currently tracking over 500,000 pieces of satellite debris circling the Earth. These bits of mostly aluminum junk whip around the planet as fast as 17,500 mph and constitute a floating minefield that active and manned space vehicles have to find their way through without being struck, or worse, punctured. And those are just the bits large enough to be tracked—those bigger than a marble. There are many more too small to keep an eye on. And the situation is getting worse, with projects such as SpaceX’s estimated 42,000 satellites or Amazon’s Kuiper project.

The wood satellites being developed won’t do much to solve that problem. However, they will help out with another one: what happens to space debris when its orbit decays and it falls back to Earth? We’ve been lucky so far. No serious impacts have yet been documented, but with all the discarded metal up there, it seems only a matter of time until something hits somebody or some important thing here on the ground. On top of that, some of it never falls all the way down, and is left as tiny bits of floating metal in the atmosphere.

Japanese astronaut and professor at Kyoto University Takao Doi tells the BBC, “We are very concerned with the fact that all the satellites which re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere burn and create tiny alumina particles which will float in the upper atmosphere for many years.”

(Fun side note: During Doi’s visit to the ISS in March 2008, he became the first person to throw a boomerang in space. It was designed specifically for microgravity.)

The proposed wooden satellites to be launched by 2023 will simply burn up harmlessly on their way down through the atmosphere.

Credit: Geran de Klerk/Unsplash

If anyone knows how to construct a wood satellite, it would be Sumitomo Forestry, a company that has been foresting and developing wood products for 400 years. Their website declares that “Happiness grows from trees.” In addition to the satellite project, the company is also in the process of designing a mostly wood, $5.8 billion Tokyo skyscraper to be completed by 2041.

The proposed satellites won’t be made of just any wood. The researchers consider its exact formulation to be a trade secret, releasing little in the way of detail. It is known that it will have to be resistant to the temperature extremes it will encounter in space, and the scientists are reportedly considering both the basic material to be used as well as special wood-derived coatings.

The wooden satellites may have some advantages in functionality. With wood not being an obstacle to various communication wavelengths, the devices may need less extensive antennae.

Even so, the proposed satellites, though novel and sort of poetic, may not ultimately be of much help. Satellite casings are just a small part of the space-junk problem—their metal and plastic insides are also left up there to bang into other stuff. There are also lots of spent rocket boosters and such in orbit.

All of which brings us back to the larger issue of all the debris that never falls back to Earth, as the wooden satellites are meant to. The problem with all this stuff isn’t what happens upon re-entry. It never re-enters at all, circling the planet ad infinitum as part of that great garbage dump in the sky.