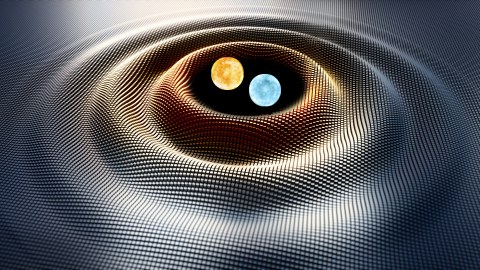

This pair of white dwarfs is spinning out gravitational waves

Image source: peterschreiber.media/M. Weiss/Shutterstock/Big Think

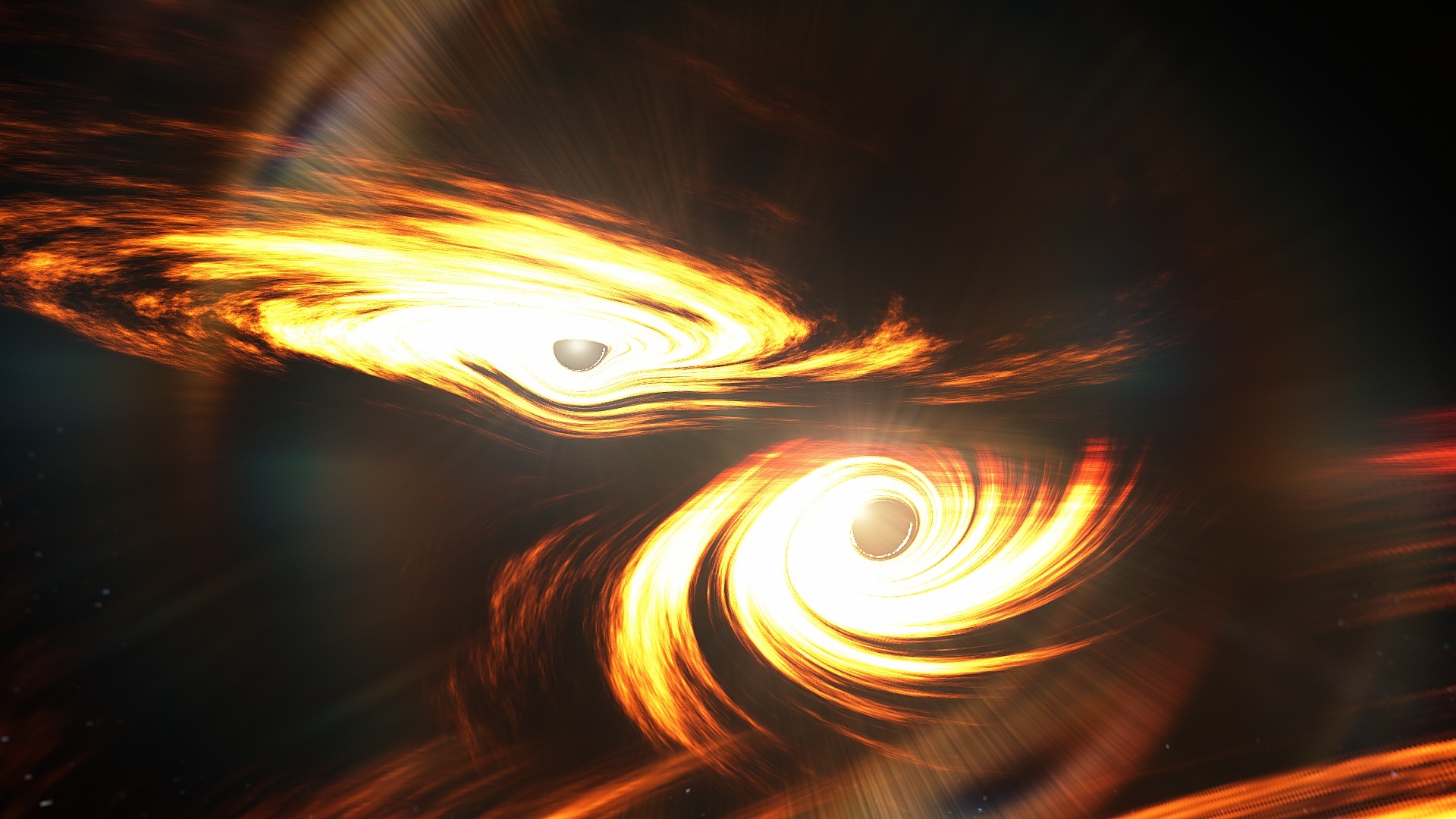

Last spring, the National Science Foundation’s Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) detected a gravitational wave produced by the collision of two huge black holes 3 billion years ago. Einstein had predicted such waves, powerful and extraordinarily subtle perturbations in spacetime, but never before had one been detected.

Though LIGO’s feat was history-making, a new, even more sensitive detection system is planned for deployment in the near future. Fortunately, scientists believe the generation of gravitational waves doesn’t require such a massive and rare cataclysm as the one detected by LIGO. One particular binary pair of white dwarf stars locked in a super-tight orbit, J2322+0509, may be sufficient to do the trick, producing, as they spin into a death spiral, gravitational waves strong enough to be detected by the new system once it’s up and running.

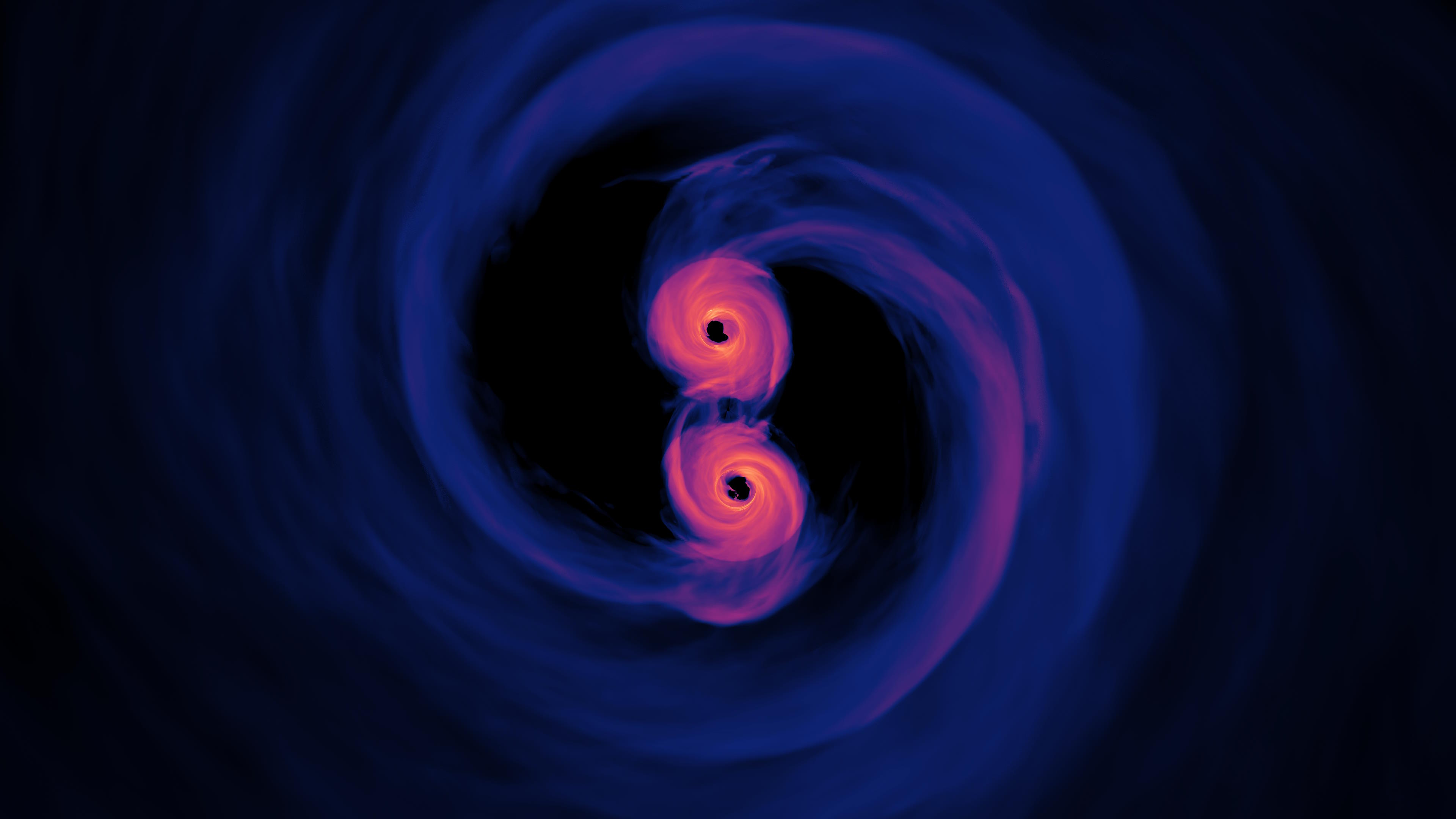

Artist’s conception of newly discovered binary white dwarf gravitational source of gravitational waves

Image source: M. Weiss/Harvard/Smithsonian

J2322+0509

J2322+0509 is a white binary system, remnants of two stars that have exhausted their fuel, leaving nothing much but their helium cores. They’re locked together in an ever-narrowing death spiral that will reach its final stage millions of years from now. However, as we observe them now, they’re orbiting in startlingly close proximity, each dwarf completing its orbit of the other in just 20 minutes plus 1 second. That’s the third-shortest orbital period astronomers have yet seen — the record-holder is ZTF J1539+5027, nicknamed J1539, a pair with an orbital period of just 6.91 minutes.

In any event, general relativity predicts that rapidly spinning white dwarf stars can produce gravitational waves, as can a few other things: the speedy rotation of neutron stars, and the explosion of supernovae. Astronomer Warren Brown says he sees the requisite scenario playing out with J2322+0509: “This pair is at the extreme end of stars with short orbital periods. And the orbit of this pair of objects is decaying.” This fits with its emanation of gravitational waves: “The gravitational waves that are being emitted are causing the pair to lose energy; in 6 or 7 million years they will merge into a single, more massive white dwarf.”

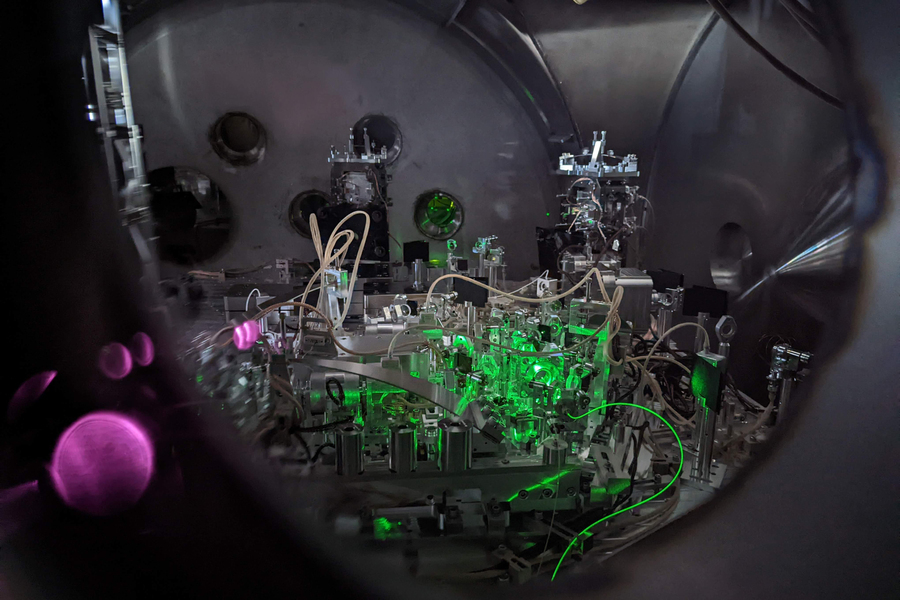

The new gravitational-wave system

The new system for detecting gravitational waves is called the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, or LISA, and it will be launched in 2034. LISA will be a triangular constellation of three satellites 50 million kilometers behind Earth as it orbits the Sun, and positioned 2.5 million km apart from each other. They’ll be “connected” by laser beams bounced back and forth between them, forming a gigantic interferometer-based detector. The distortion of spacetime produced by a gravitational wave passing through the lasers will perturb the pattern they create to some tiny, likely subatomic degree, allowing LISA to detect and study that wave.

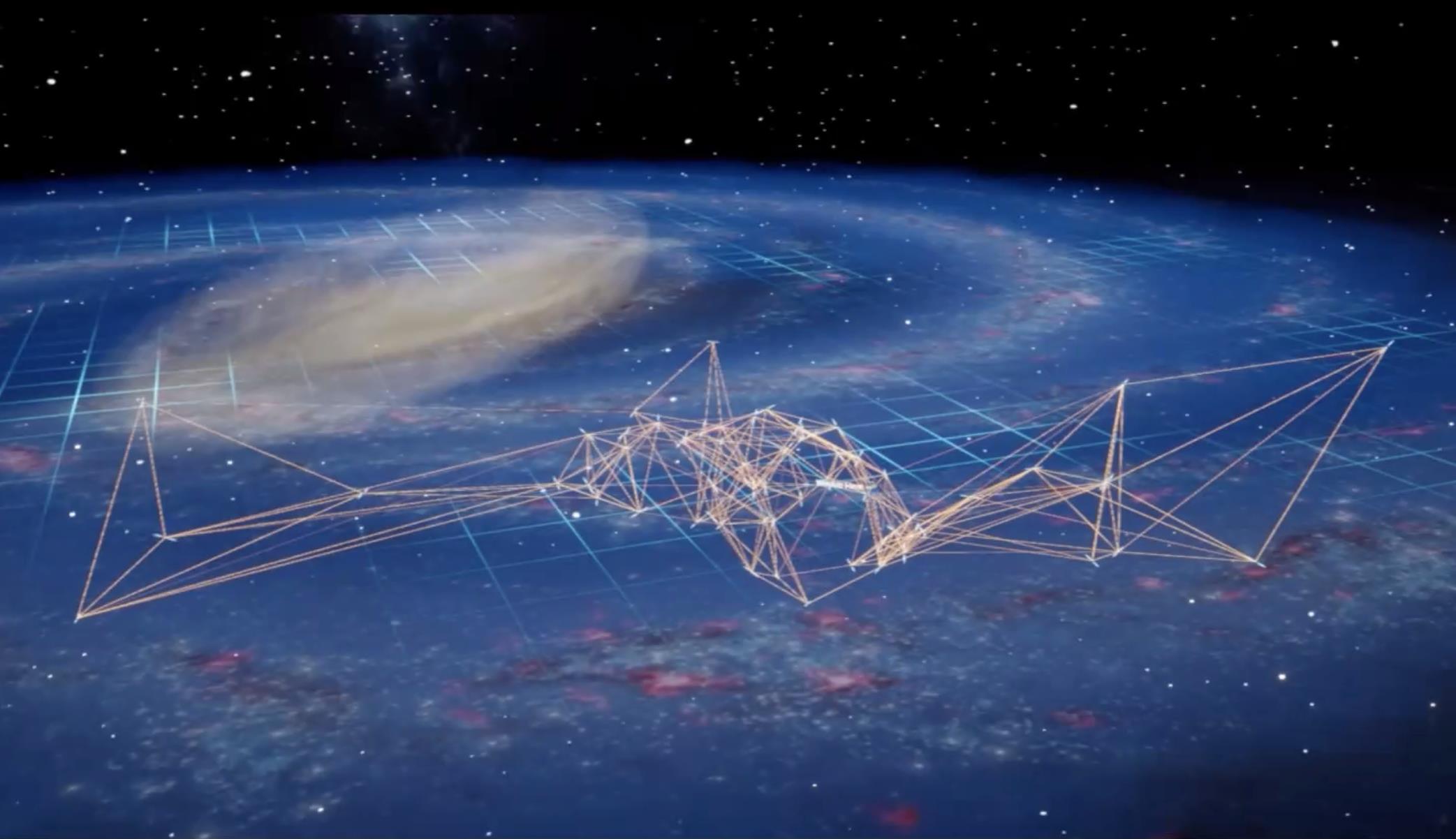

Schematic illustration of the LISA array’s orbit as it revolves with the Earth around the Sun in one year.

Image source: ESA

Perfect for LISA

In order for LISA to deliver on its scientific promise, of course, some gravitational waves will have to ripple its way fairly soon in order to verify that it’s working as hoped. Astrophysicist Mukremin Kilic says, “Verification binaries are important because we know that LISA will see them within a few weeks of turning on the telescopes.” Serving as a test run of sorts, “This detection provides an anchor for those models, and for doing future experiments so that we can find more of these stars and determine their true numbers.”

Finding J2322+0509 poses something of a relief to scientists. Although it’s believed that white dwarf binaries are common, she says, “There’s only a handful of LISA sources that we know of today.”

Especially exciting about this binary is its orientation toward us and what that may signify as to the strength of gravitation waves it emits. “This binary was difficult to detect,” says Brown, “because it is oriented face-on to us, like a bull’s eye, rather than edge-on. Remarkably, the binary’s gravitational waves are 2.5 times stronger at this orientation than if it were orientated edge-on like an eclipsing binary.”

Brown concludes, “We’re finding that the binaries that might be the hardest to detect may actually be the strongest sources of gravitational waves.”