We may not be alone in the Universe. Should we reach out?

- We have sent messages into space before, hoping to reach out to any interstellar intelligences. Such a message is challenging to compose.

- Some argue that maybe it’s better not to send an intentional message at all.

- In any case, any message we send is likely to be a simple, “We’re here."

SETI has been looking for life among the stars since 1985. For even longer than that, we have wondered whether we are alone in this massive Universe. And so far, while the stars are brilliant and beautiful, they are quiet.

It seems we are alone.

Rather than just passively searching, some take a more proactive approach. They believe we can announce our presence — in other words, help ETs find us. It’s the “personal ad” method: Young civilization looking for a partner to contemplate space and hold slow conversations over incredibly huge distances.

What would you include in such a message? Could such an approach even work? Some adamantly argue that this is a bad idea. After all, while we are hoping for a “soulmate” civilization, we may end up being catfished by the creepy civilization bent on genocide and planet exploitation.

Sending messages is not a new idea

We have sent messages to the stars before, hoping that someone out there will find them — and if not answer them, at least know we are (or were) here on Earth.

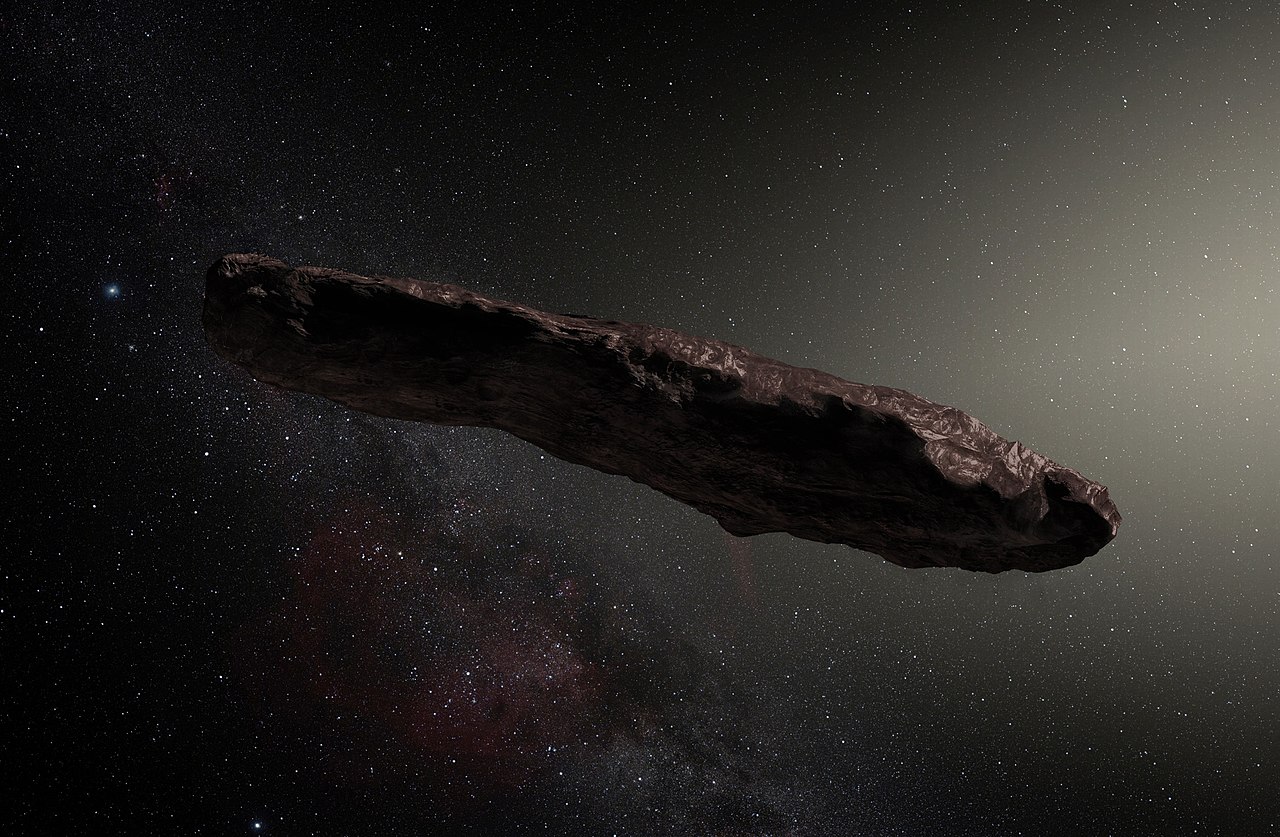

Some of these are physical messages, placed on artificial objects we sent into space with a velocity so large that they escaped the pull of our solar system. These objects will travel forever through the void of space — that is, unless they crash into a star, fall into a black hole, or someone (or something) finds them.

The first two were Pioneer 10 (which explored Jupiter) and 11 (which visited Jupiter and Saturn, and also studied the overall environment of our solar system and asteroid belt). Both of these have a small plaque with an image of a male and female human form, along with information conveying that these probes came from Earth. Later, the Voyager 1 and 2 probes carried a “Golden Record” with images and sounds of nature, various tracks of music, greetings, and a written message from President Carter and U.N. Secretary-General Kurt Waldheim.

Other messages have been beamed to the stars by giant radio telescopes, crafted in such a way to appear from an intelligence (rather than from a natural source) and to be comprehensible (we hope) to another civilization. Then there’s METI: the proactive sister of SETI. “Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence” seeks to craft and transmit messages that one day may be found by another civilization.

The Dark Forest

Yet one of the most terrifying possibilities is that maybe it’s better not to put a personal ad out there at all.

The Drake Equation is a way to calculate the number of alien civilizations with which we can communicate. It is the product of several probabilities, some of which we have a pretty good understanding of (the star formation rate, the fraction of stars with planets) to ones we have no clue about (the fraction of planets where life develops, the fraction of times that life develops intelligence, the lifetime of such a civilization).

So far we’ve found precisely zero civilizations out there. Some people argue that this is because life is very rare. Others suggest that it is rare for life to reach a technological level where it can communicate with the stars. Or perhaps, once a civilization reaches this level of technology, it doesn’t live for long before it blows itself up or changes its planet’s climate so much that the civilization ends.

But there’s another possibility called the Dark Forest theory, introduced by science fiction writer Liu Cixin. The basic idea is that there are civilizations out there, but they are all staying quiet. They know it’s not a good idea to reveal your presence to a hostile Universe. There could be loads of civilizations that are ready to destroy each other. People who adhere to this line of thought are passionate. We shouldn’t talk. We shouldn’t respond. We should just shut up.

Well, I’ve got bad news for you: This may be impossible. Dr. Sheri Wells-Jensen is an Associate Professor in Linguistics and TESOL at Bowling Green State University. She’s on the Board of Directors of METI. “That horse, as they say, has left the barn,” she tells Big Think.

“Our military radars are blasting into space already. Our atmosphere displays oxygen. It also displays the evidence of industrialization. We can refuse to say ‘hello’, but our presence is knowable. We can either be knowable and be speaking, or we can be knowable and be silent. It’s a choice between message and no message… not a choice between hiding and revealing ourselves.”

We have been sending messages to one another for about 100 years now — long enough to make an expanding bubble of emissions with a diameter of about 200 light-years. We don’t have to announce our presence — any alien civilization or probes within this bubble have access to the history of our civilization, from Hitler in the 1936 Olympics to the TV show Ally McBeal. (Of course, there are some pretty big caveats to this. The power of any such signal would be very, very low and difficult to detect. There’s also the fact that, while it’s 200 light-years across, our radio bubble is still quite small.)

Defining humanity

So let’s say we do want to compose an intentional message. What should be in it? Is it possible to sum up humanity in a brief message, comprehensible by an alien intelligence?

The composers of the Golden Record attempted diversity. Humans gave their interplanetary greetings in 55 languages, from Japanese to French to Bengali. A similar attempt to sum up humanity was seen in the music choices, which spanned from a Pygmy girl’s initiation song from Zaire to a Peruvian wedding song to “Johnny B. Goode” by Chuck Berry.

Still, attempting to sum up the diversity of humanity is challenging, if not impossible.

Wells-Jensen has thought a lot about how to write — or read — a message from extraterrestrials. She’s also blind. She believes it’s simply not possible to speak for all of humanity.

“Diversity is not averageable,” she tells Big Think. “When I go to events that claim to be inclusive, for example, I, as a disabled person am regularly excluded… this happens even when the event is literally about diversity. We cannot represent our diversity to others when we rarely represent it to ourselves.”

Then there is the flip side of the coin: Perhaps we don’t want to show the full range of humanity.

Big Think talked to Jason Batt, a science fiction author, mythologist, and futurist.

“Do we hide parts of our story?” he asks. “In a way, it’s kind of the question of a first date, like how much do you get into your nasty baggage? Because you want a second date… When we go out and we represent the human race, I can no longer divorce Hitler from myself.”

We can’t necessarily lie about it either. Remember that expanding bubble of radio emissions? That’s out there too, along with any intentional message we may send. We can’t hide Hitler, infomercials, or the Kardashians. It’s already there.

Simplicity is best

Let’s remember that communicating with any extraterrestrial intelligence will be remarkably difficult. We won’t have a shared biology, culture, or planet. We might not even have the same chemistry. We can’t talk to dolphins and elephants on this planet — what makes us think we will have more luck in space?

So what can we do?

“Something simple. We exist. We are reaching out. Full stop,” Wells-Jensen tells Big Think. Anything else might be a bit more ambitious — at least for now.

Perhaps a good example of this is the “Wow! signal,” discovered in 1977 by the Big Ear radio observatory. It was so strong that when astronomer Jerry R. Ehman discovered it, he circled it on the computer printout, writing the word “Wow!” While there might be a natural explanation (scientist Antonio Paris suggested in 2017 that perhaps it was from a comet), its true nature remains controversial. Because it is narrowband, the signal is difficult to explain naturally. It’s at 1,420 MHz, the frequency of hydrogen emission, which may be a natural choice for a civilization that wants to communicate in the language of science. Its strength and incredibly brief nature (72 seconds) make it one of the best candidates for extraterrestrial intelligence we’ve found so far.

Thirty-five years later, we sent a reply composed of a group of tweets and a message from Stephen Colbert urging the aliens not to eat us. While there is little chance anyone listening to the message would be able to understand all of this, a repeating header was included, hopefully showing that the message was intentional and not natural.

While the Wow! signal may indeed turn out to have natural origins rather than of an extraterrestrial intelligence, it may be a good example of what contact with a neighboring civilization might look like.

“We’re here.”

“We’re here, too.”

A conversation that takes 1,000 years.