NASA Scientists Discover “Kittens” Within Saturn’s F Ring

Saturn’s rings are iconic. But it’s far from the only planet to have them. Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune all have rings. Theirs however aren’t as prominent, and thus they’re harder to see.

The 6th planet’s famous formations go from A to G. The rings aren’t in alphabetical order but were named in the order in which they were discovered. From a distance they look so smooth you could skate on them. In actuality, they’re made up of a multitude of ice particles and ice-covered rocks ranging from an inch or so long to about the size of a mid-size sedan.

These rings were formed when comets, asteroids, perhaps even a whole moon was pulled into this gas giant’s herculean grip. Whatever bodies they were soon crumbed apart, due to the oppressive gravity. The detritus began orbiting the planet, encircling it and over time formed the ring-like pattern we recognize today. The rings are thought to be relatively young, compared to the age of the universe. So if we lived eons ago, Saturn might not have had them.

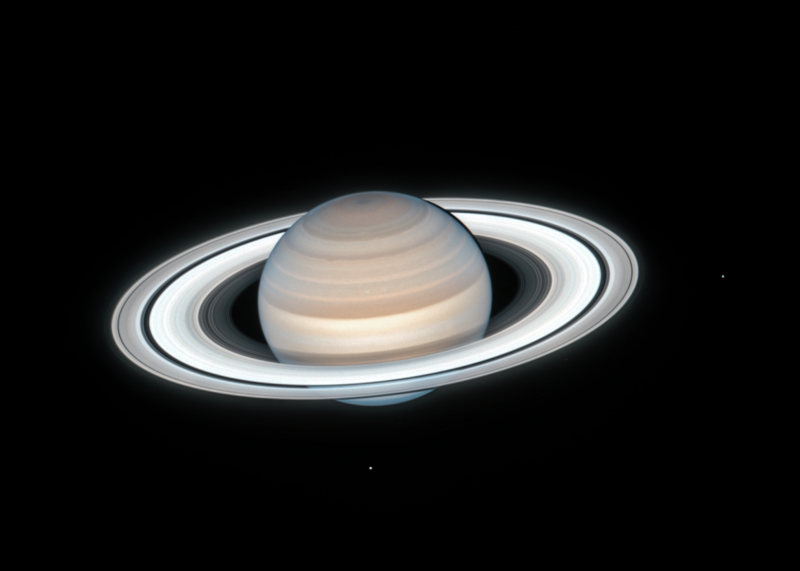

The Hubble telescope gave us our first up-close views of Saturn’s rings and allowed us to understand their composition. Recently the Cassini spacecraft ended its 20 year mission in a wholly dramatic fashion. It burned up in a fiery free-fall through the planet’s gaseous atmosphere. First launched in 1997, Cassini entered Saturn’s orbit in 2004 and there it remained until September 15, when it took its nosedive. In all that time, the spacecraft transmitted home oodles of information about Saturn and its rings.

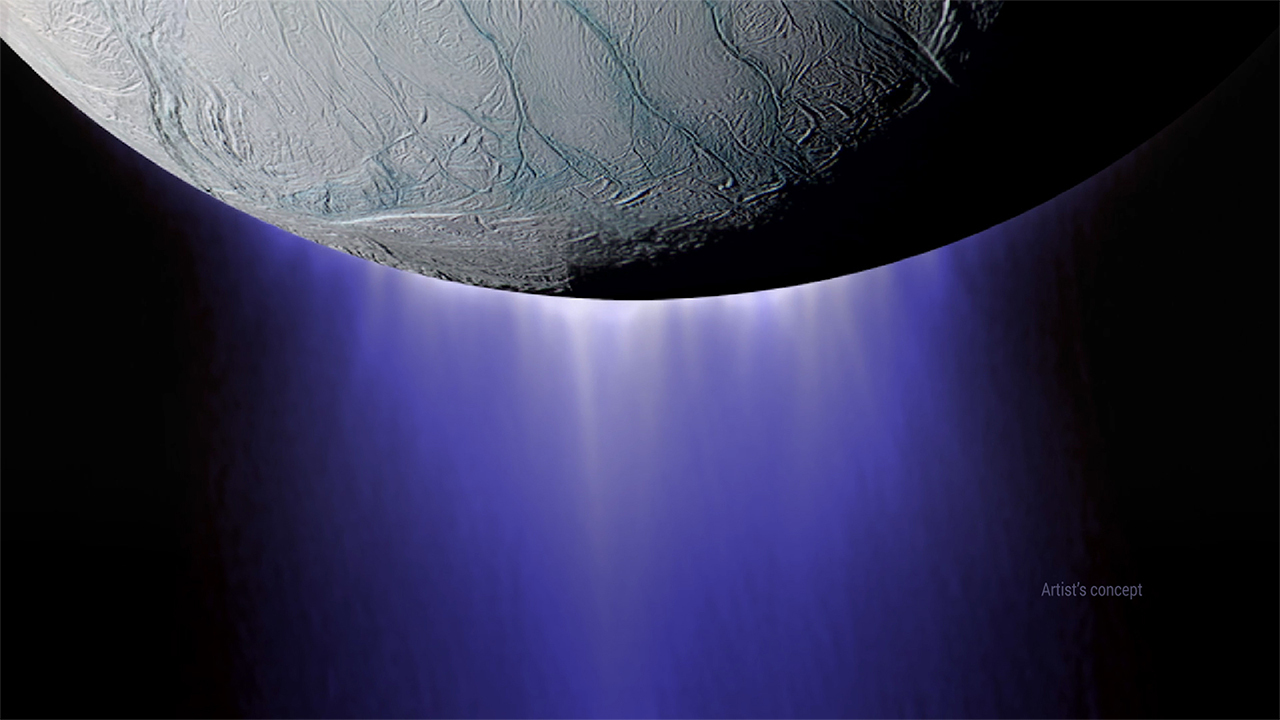

Particularly, Cassini allowed us to better understand the material that makes up the rings and how the pieces interact with one another. Cassini also gave us a good look at Titan and Enceladus, two of Saturn’s moons which could possibly harbor life, though perhaps the unicellular kind, huddling around volcanic vents, deep beneath the liquid seas of each. The Cassini spacecraft even launched the Huygens probe which visited Titan.

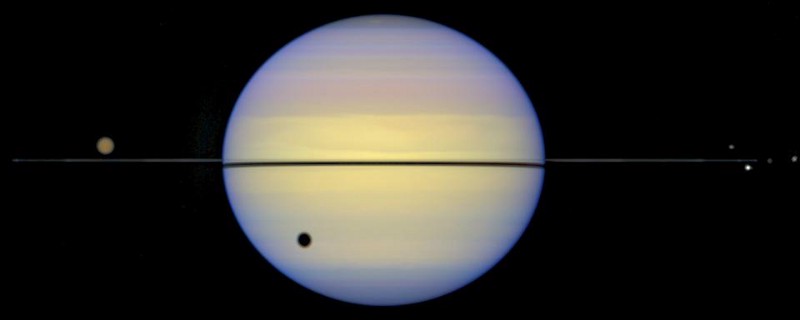

Saturn’s rings. The F ring marks the outer boundary of the main system. NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

Now, NASA scientists are sifting through some of the last transmissions from Cassini. And what they’re finding are kittens. You read that right. Saturn’s F ring has 60 identified “kittens,” thus far. These are moonlets or baby moons and other clumps of detritus that get mashed together within the ring when they collide. Each kitten is considered to be about 72 ft. to 2.3 miles (22m to 3.7km) across. When enough of these clumps have come together and the body is a sufficient size, it becomes a moonlet.

Saturn’s F ring is estimated to contain approx. 15,000 mid-size kittens. NASA scientists, being the hoot they are, decided to unofficially name these bodies things like Garfield, Sylvester, Socks, Fluffy, and Whiskers. Each has an official title as well. For instance, there’s Alpha Leonis Rev 9 which has been nicknamed Mittens.

Cassini took photos of the kittens. NASA scientists are now evaluating them through a process known as stellar occultations. This is when a star passes behind Saturn’s rings. From Cassini’s point of view, such an event illuminated the particles and rocks that make up the rings.

Kittens are hard to make out. “The cameras aren’t good enough to see the features we’re finding, except maybe the very largest ones,” Larry Esposito told Space.com. He’s the Cassini scientist in charge of finding and naming them. During its 13 years in orbit, Cassini witnessed 150 such occultations.

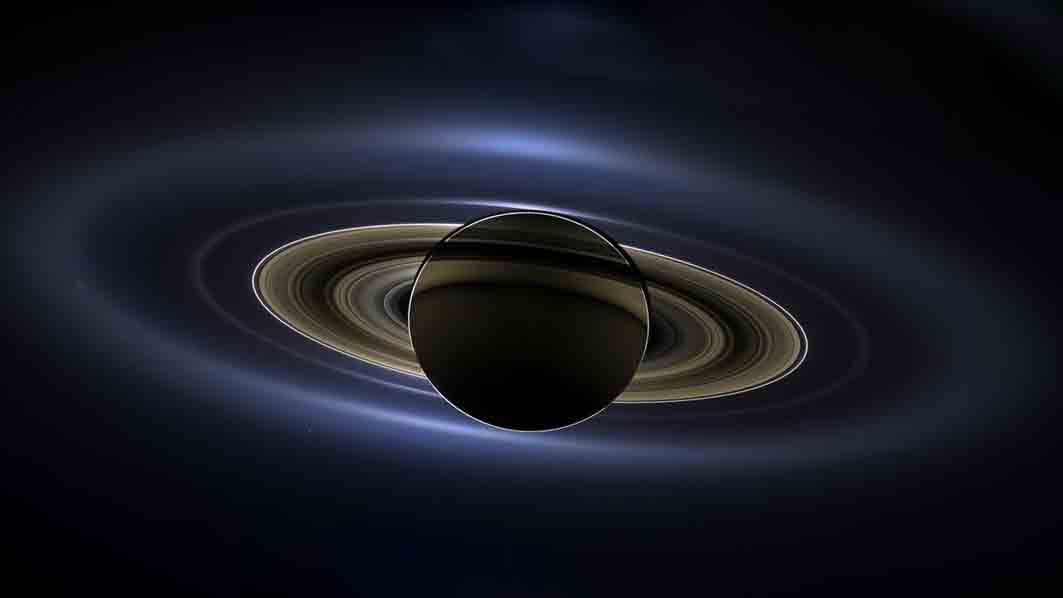

A Titan-sized moon may have broke up in Saturn’s orbit, forming the rings. Steven Hobbs © 2010. CICLOPS. Cassini Imaging. NASA.

Esposito explained how they assess such moonlets: “We use the flickering of light to measure the structure in the rings just as if you were on your porch watching a car drive by at night where the headlights go past the picket fence. The headlights would blink on and off, and then you could tell how many pickets there were and how wide they were.”

Although the rings aren’t exactly uniform like fence posts. Albeit an imperfect system, “You could tell how much light went through at every moment and use that to determine the amount of material at that position in Saturn’s rings,” he says.

Unfortunately, the kittens aren’t permanent fixtures. The environment in the F ring is such that fragments are bouncing off one another all the time, forming clumps and then getting smashed apart again. Keeping track of particular kittens may prove impossible.

Despite uncovering the mysteries surrounding its rings, there are still plenty of things we don’t know about Saturn. The exact length of one of Saturn’s days isn’t currently known, for example. There are also weird goings on in its magnetic field that astronomers don’t quite get, yet. Future missions will likely expand our understanding.

To see some of the best new photos Cassini took on its swan dive into oblivion, click here: