Cut, paste, life

Credit: Netflix

I recently watched the four-part documentary series Unnatural Selection on Netflix.

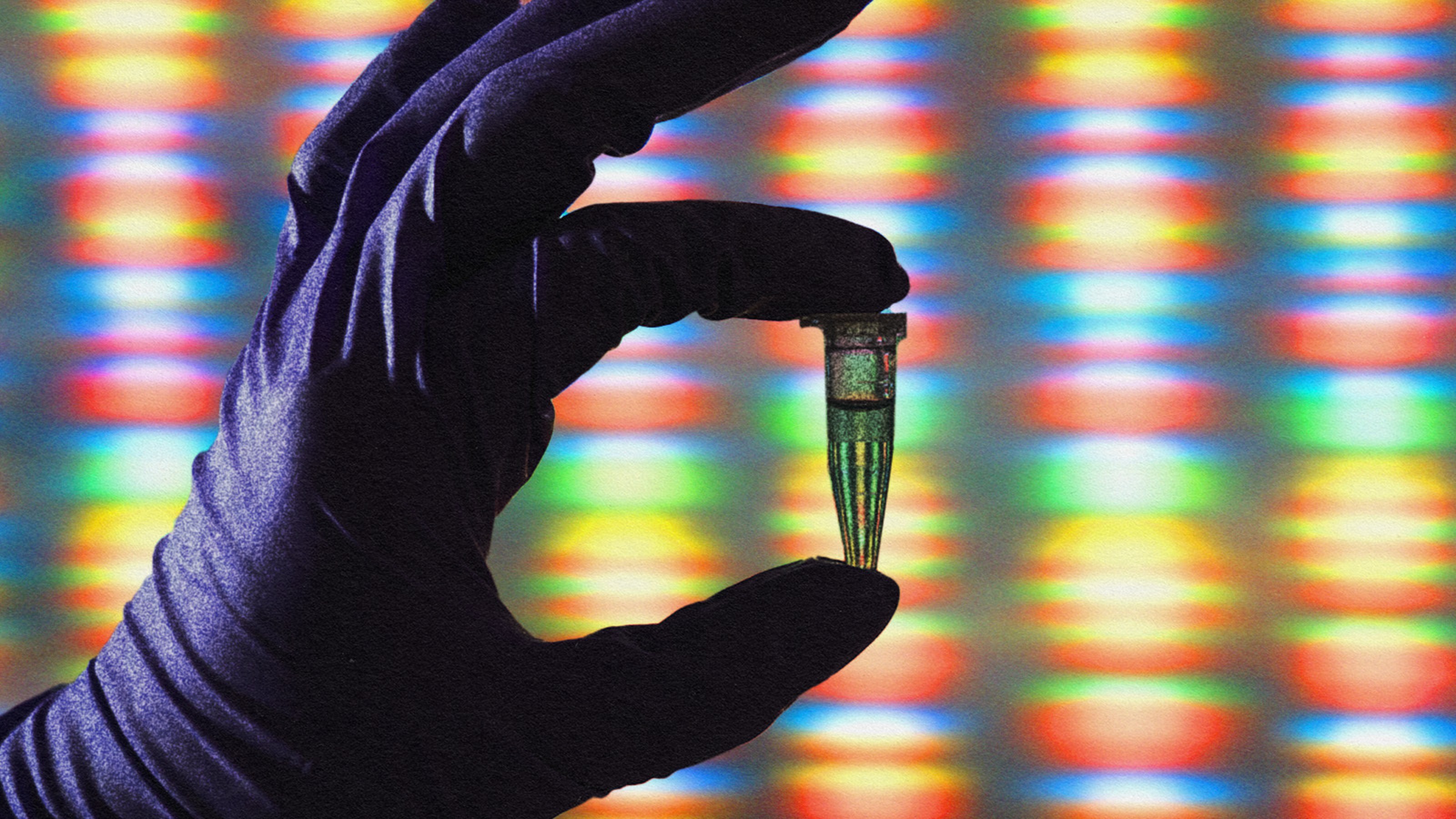

The topic, as you may have guessed, is the direct manipulation of the genome of any living being, be it from plants, animals, or humans. The science is based on CRISPR-Cas9, the technology that allows scientists to cut out a piece of a genome and replace it with another. “Hacking life” is not an exaggeration.A useful image is to compare a creature’s DNA to a book, written with a very long sequence of four letters—A, C, G, and T, the four base pairs that determine its genetic characteristics. (The letters stand for Adenine, Cytosine, Guanine, and Thymine, the constituents of the double-stranded DNA molecule.) We each have our own genome book, our genetic fingerprint, as does any other living creature. The individual order of the letters is essential. CRISPR allows scientists to take out one or more of those letters and replace it with another sequence, like editing parts of a text. Not surprisingly, the first episode of the Netflix series is titled “Cut, Paste, Life.” In short, the technology allows for scientists to change an organism’s DNA and pass those changes on to future generations

For the first time in history, we can actually design creatures, and their traits, as we please. This is not the same as the age-old genetic selection procedures, where you’d breed dogs or cattle, or hybridize plants, to optimize a species by normal reproductive techniques. This is surgical genetic engineering, targeted at specific genes or groups of genes responsible for specific traits.

This is the kind of science that makes us marvel . . . and panic. We marvel because the medical applications are absolutely mindboggling. Single-gene disorders that affect millions—like cystic fibrosis, hemophilia, and sickle cell disease, to name a few—should be soon a thing of the past. Even more complex diseases, hereditary or not—like different kinds of cancer, heart disease, mental illness, and HIV infections—are also, in principle, curable. (A centerpiece of the series revolves around an HIV-positive young man’s heroic self-sacrifice as a human guinea pig.)

The excitement is palpable, and for different groups: first, those afflicted with the various diseases, who desperately wait for a cure. Then, the big pharma companies that are aggressively developing treatments for many of those diseases, with an eye on the huge profits ahead. The scientists, of course, realize that they are on the verge of a profound, historical revolution. Lastly, the government, knowing only too well that such technologies will change the nature of warfare.

This is where the trouble begins. CRISPR is not like nuclear weapons, which require huge resources and laboratories. CRISPR can be done in a garage lab, by unlicensed practitioners. They are the biohackers, individuals, or start-ups that realize that they can beat the system, potentially developing treatments before big pharma, acting as true science heroes. They are justly outraged by the cost of some of the preliminary treatments, ranging from hundreds of thousands to millions of dollars. They are irate at the regulatory barriers that slow down research.

Some want to show that you don’t need to work in a university or an industrial lab to change the world. They believe, sometimes in earnest, that such wondrous treatments should be low priced, available for the many millions who need them worldwide. As Unnatural Selection shows, they often act impulsively, with a strong sense of social justice as their key motivation, not thinking deeply enough about the serious risks involved in treating humans with untested drugs.

The film shows, quite dramatically, how initial enthusiasm turns into deep moral self-questioning, as it should. You can’t fool around with other people’s lives, even if you are well-intentioned.

Deep, dark questions

And then there are the other motives—the dark ones. This sort of technology opens the biggest of Pandora’s boxes ever conceived. Are we to design brand new species? New kinds of post-humanoid creatures, with physical and intellectual powers vastly superior to ours? Is there a line to be drawn somewhere between us and superhumans? How will this research be regulated? Who will decide what rules apply or don’t? And how will these rules be enforced across the globe, garages included?

The biggest danger of CRISPR technologies is that enforcement is practically impossible. There will be someone, somewhere, breaking the law, messing with genes in ways that are truly dangerous. Dangerous for us, for the environment, for biodiversity, and for the future of our species and the biosphere.

This is why CRISPR is so fascinating and terrifying. Every revolutionary scientific technology brings with it the promise of good and the threat of evil. How could we not want to alleviate so much human suffering, such horrible deaths? Isn’t this what science is ultimately about? But the different interest groups have conflicting agendas, and they are not talking to each other.

Genetic selectivity is here to stay. This we know. The question is, How far away from ourselves are we willing to go before we realize it’s too late to go back? Or, maybe, this is where we must go, reinventing ourselves and the world around us.

Many very smart people believe that this is our evolutionary destiny. If this thought doesn’t make your stomach turn like it does mine, then, perhaps we are already halfway there.

The post Cut, Paste, Life appeared first on ORBITER.