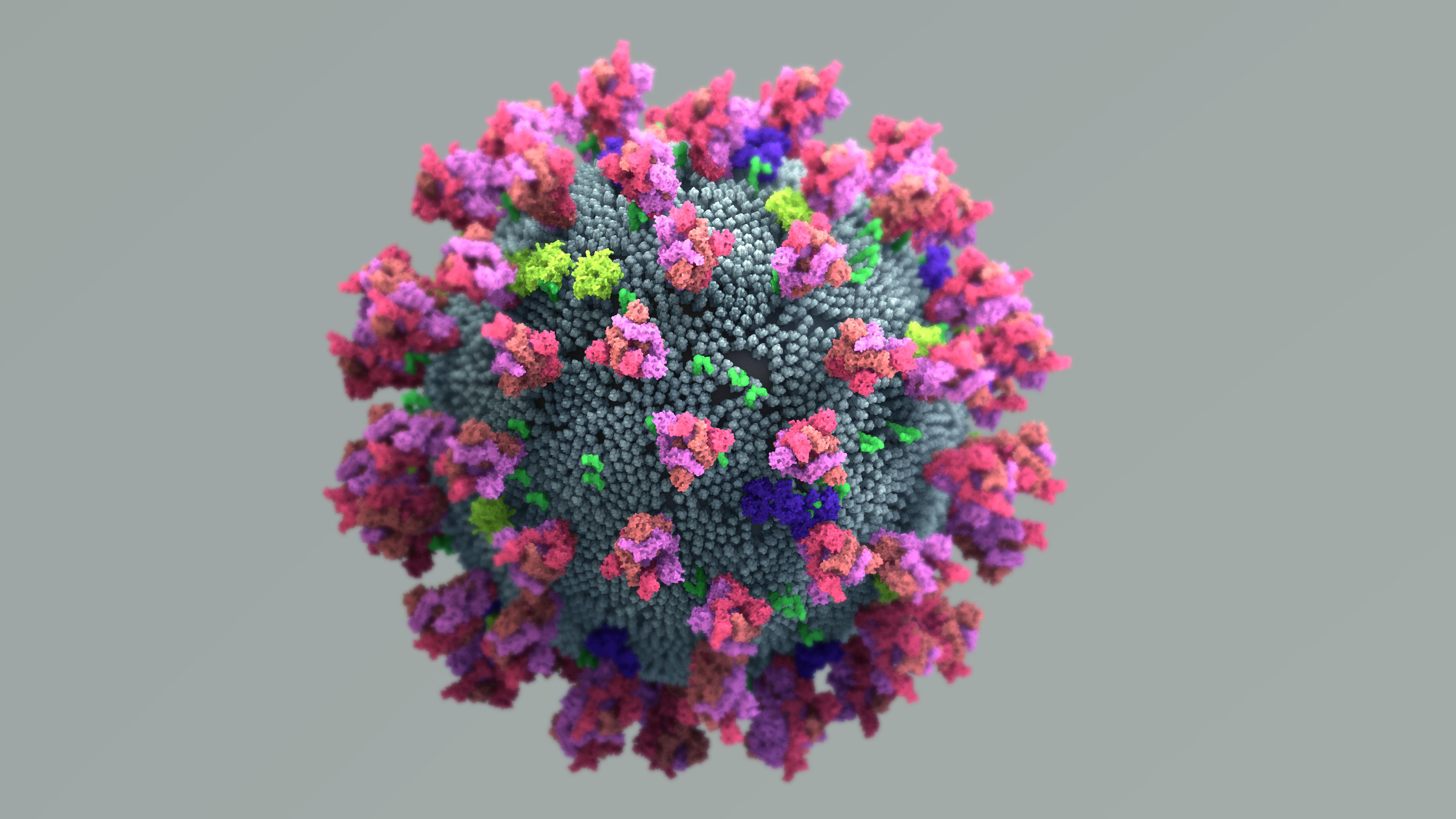

KATE THE CHEMIST: One thing that I found that was super interesting is that this virus actually has a really weak membrane on the outside. And so since the membrane is actually kind of weak when we wash our hands it's not really the soap that's killing the virus, it's that action. It's the movement that you're doing with your hands. So when you scrub really hard you are actually ripping apart that membrane since it's so weak. And so it's that 20 seconds of scrubbing, of using your fingernails and using a scrub brush to actually clean and rip that virus apart so that your hands therefore can be clean when you do a final rinse and that wash rinses the virus off. The cool part about our soap is that it has two different sides. It's hydrophilic and it's hydrophobic. So the hydrophobic part is the part that actually binds to that virus so it hands onto kind of like a middle school crush like you grab onto someone and hang to them really tight and that's what the hydrophobic side does. It grabs that virus and hangs on.

The hydrophilic side is the side that actually likes water. So when the water turns on, the hydrophilic side grabs onto the water molecules and the hydrophobic side grabs onto the virus and so each one has a job. One hangs onto the water, one hands onto the virus and then that entire molecule section is going to drop down and it flushes off your hand down the water stream into the sink. So the scrubbing motion breaks the virus apart and then the soap itself bonds to the water and the virus to remove it completely from your hands and make sure you're completely safe.

Dr. Kate Biberdorf is a scientist, a science entertainer, and a professor at the University of Texas. Through her theatrical and hands-on approach to teaching, Dr. Biberdorf is breaking down[…]

The physical action of handwashing plus the properties of soap is a one-two punch for the virus.

▸

1 min

—

with

Sign up for the Smarter Faster newsletter

A weekly newsletter featuring the biggest ideas from the smartest people

▸

7 min

—

with

Related

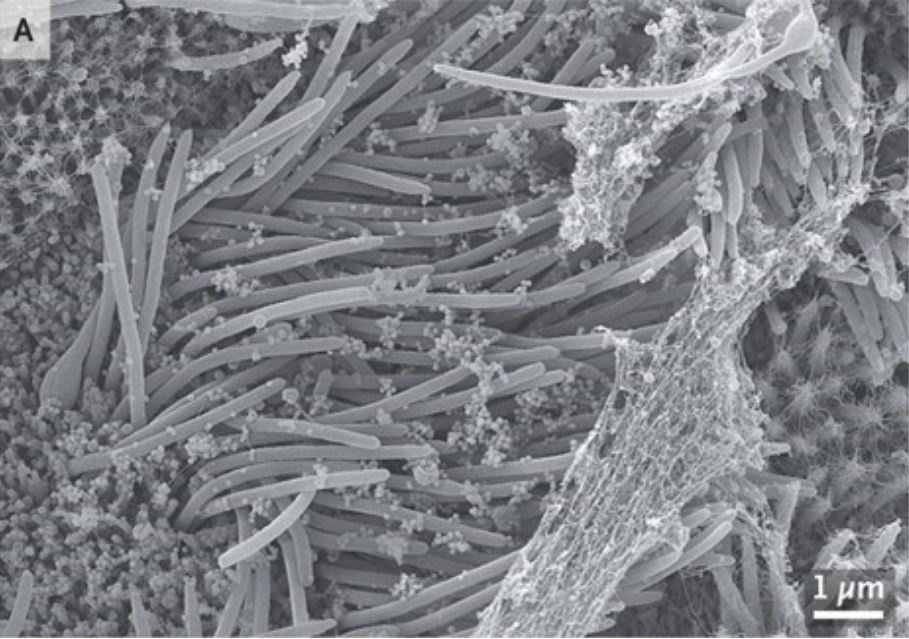

Ultrasound might be able to damage the novel coronavirus in the same way an opera singer’s voice can shatter a wine glass.

Cotton mask fibers prove 33 percent more effective at blocking viruses in trials.

The researchers trained the model on tens of thousands of samples of coughs, as well as spoken words.

The images were published in the New England Journal of Medicine and show how prolific coronavirus can become in a mere four days.

Dr. Kate Biberdorf explains why boiling water makes it safer and how water molecules are unusual and cool.

▸

3 min

—

with