The TESS satellite caught a comet ‘burp’

Image source: Farnham et al./NASA

- A comet produces and unexpected explosive ejection of ice, dust, and gas.

- NASA’s TESS satellites captures the whole thing by accident.

- The “burp” may have left a crater 65 feet across. That’s quite a burp.

When NASA trained their Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, AKA TESS, at Comet 46P/Wirtanen, they were merely looking for a body with which they could test out their system. TESS’s mission is observing some 200,000 stars for evidence of exoplanets, but they knew the comet was going to pass through their observation window and that it would be bright. It seemed a good test case. Little did they expect they would catch it belch ice, dust, and gas.

A paper describing the TESS team’s observations have been published in the November 22, 2019 issue of The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Image source: NASA/JPL

Witanen

According to the paper’s lead author, astronomer Tony Farnham of the University of Maryland (UMD), “Wirtanen was a high priority for us because of its close approach in late 2018, so we decided to use its appearance in the TESS images as a test case to see what we could get out of it.” “We did so, and we were surprised,” he explained in a University of Maryland press release.

What came out of Comet Wirtanen was extensive. The team’s early estimate is that about 2.2 million pounds of materials were expelled during the “burp,” sufficient to leave a crater behind about 65 feet across. (Further analysis is ongoing.) Considering the diameter of the comet is believed to be about 1.2 kilometers, that’s a significant cavity.

Comet burps have been seen before, but never observed in the entirety as TESS has done. The one-hour blast occurred on September 26, 2018 followed by a gradually increasing eight-hour period of brightness the astronomers suspect was actually light reflecting off of an expanding cloud of ejected ice, dust, and gas. In about two weeks the comet’s brightness faded away.

Aside from catching the entirety of Comet Wirtanen’s “indiscretion,” what’s remarkable about TESS’s observations was the comprehensive manner in which they documented the entire outburst. The satellite takes detailed, composite images every 30 minutes, so, says Farnham, “With 20 days’ worth of very frequent images, we were able to assess changes in brightness very easily. Such imagery That’s what TESS was designed for, to perform its primary job as an exoplanet surveyor.”

Comet Wirtanen’s closest approach to Earth was long after the event, on December 26.

Of their good luck, he continues, “We can’t predict when comet outbursts will happen. But even if we somehow had the opportunity to schedule these observations, we couldn’t have done any better in terms of timing. The outburst happened mere days after the observations started.”

Image source: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

TESS

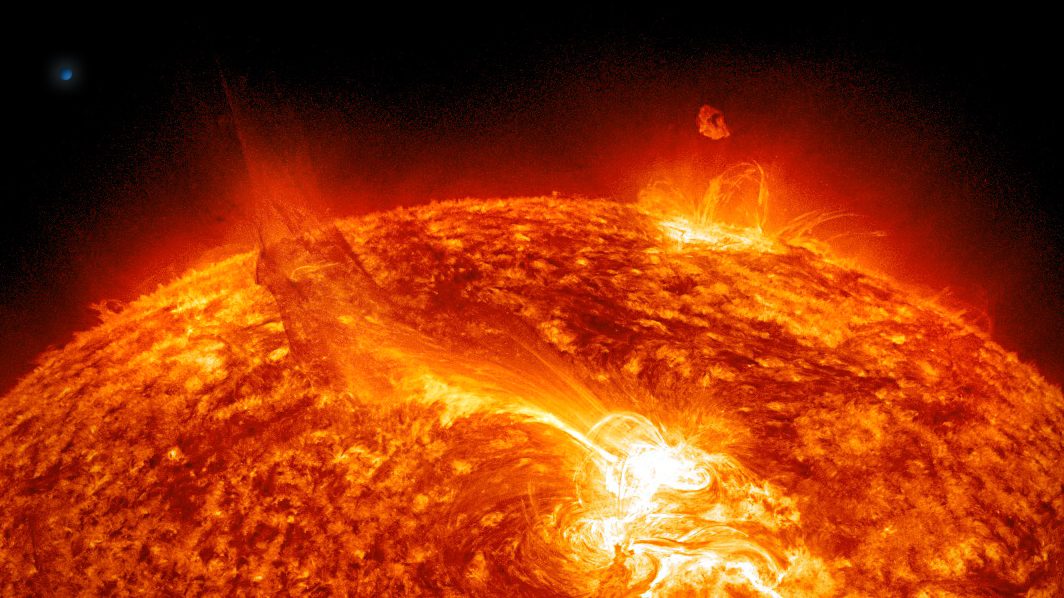

TESS was launched aboard a Falcon X rocket on April 18, 2019 from Cape Canaveral. While the mission was originally intended to last just a couple of years, it’s already been extended to 2022. Its goals are ambitious: The team hopes to find 10,000 alien worlds in just the first two years. It’s off to a good start, having already found some.

Hopefully, this isn’t the end of TESS’s observations of comet burps. “We also don’t know what causes natural outbursts,” says Farnham, “and that’s ultimately what we want to find.”

NASA theorizes that burps may be caused by a thermal event that in which a heat wave reaches a pocket of volatile ices that expands and rapidly, explosively vaporizes. They also propose that it could be due to some more geological event, such as the collapse of a mountain that exposes that same ice to sunlight and heat.

Fanrham thinks that chances of further encounters are good: “There are at least four other comets in the same area of the sky where TESS made these observations, with a total of about 50 comets expected in the first two years’ worth of TESS data. There’s a lot that can come of these data. We’re still finding out the capabilities of TESS, so hopefully we’ll have more to report on this comet and others very soon.”