5 types of climate change deniers, and how to change their minds

Matt Artz via Unsplash

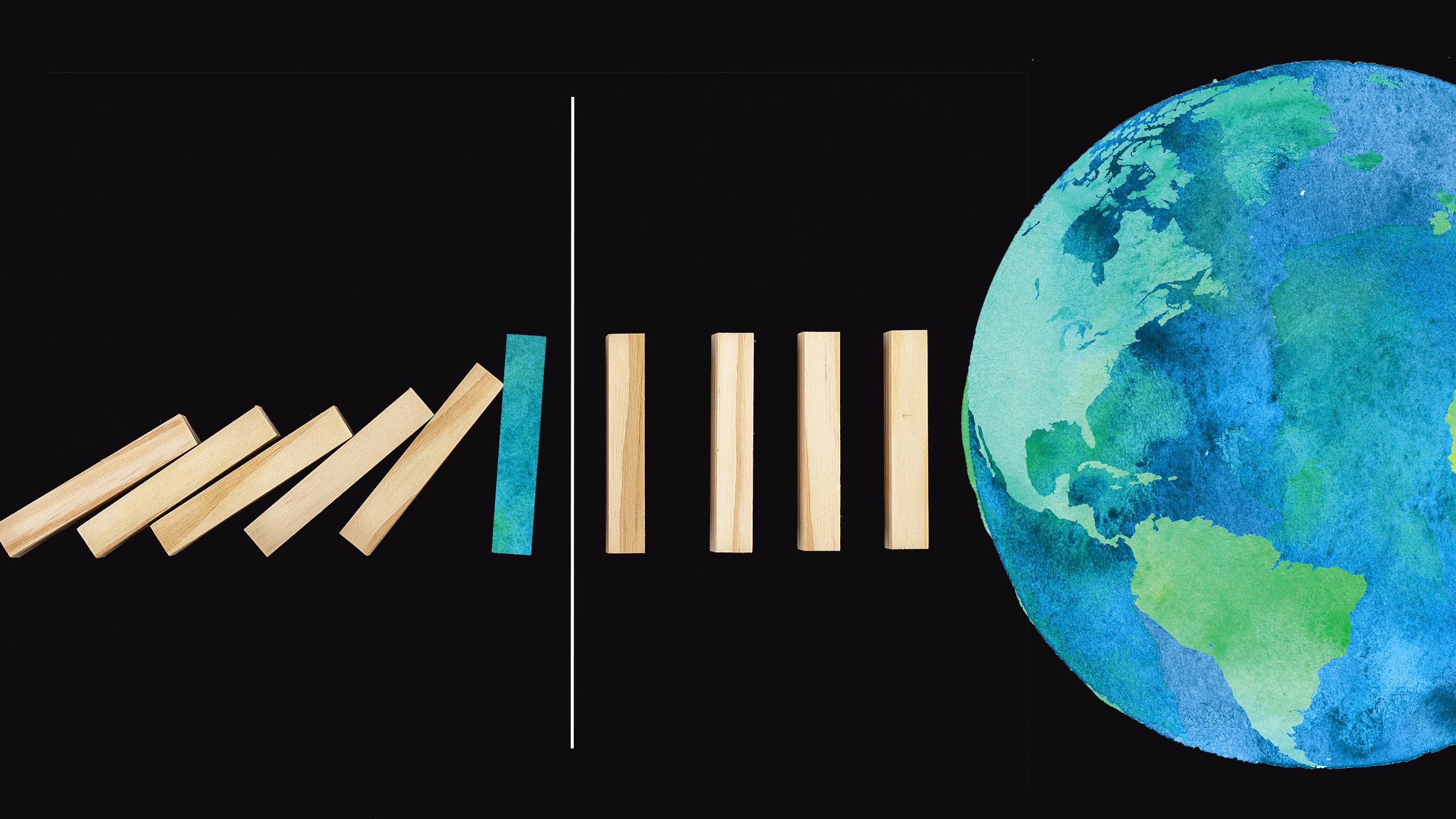

- Climate change is easily one of humanity’s greatest threats, and a mountain of data and evidence support this assertion.

- Despite the evidence, only 71% of Americans believe that climate change is real and primarily driven by human activities.

- People can and do change their minds about climate change. Trying to convince people to change their minds is often more about picking the right target than it is providing the right arguments.

Michael Shermer, founder of Skeptic magazine, recently changed his mind about climate change.

Dean Mouhtaropoulos/Getty Images

Do facts matter? In an objective sense, yes, of course they do. It’s a fact that the Sun rises in the East and sets in the West, and no amount of hemming and hawing will change that. A better question might be: Do facts matter to people?

When we look at topics with seemingly straightforward, fact-based answers, the disheartening conclusion is that no, facts do not matter to people, at least not more than belief. The rate of deadly diseases dropped precipitously after the introduction of vaccines, but a highly anti-vaccination community in North Carolina just had a sizeable outbreak of chickenpox. Eratosthenes used some fairly simple math to demonstrate the Earth is a globe 2,000 years ago, but plenty of people still believe the Earth is flat. Through multiple discrete sources of evidence, 97% of climatologists agree that the Earth is warming, and human behavior is to blame, but only 71% of Americans believe that global warming is happening at all, let alone human-driven global warming.

Reality doesn’t care about people’s beliefs; it will continue to behave as it will regardless of its polling numbers. So, part of the necessary work in preparing against reality’s variety of risks and threats is convincing people that those risks and threats exist in the first place. Can you change the mind of a climate change denier? And if so, how?

Reconsidering the evidence

To answer the first question, it does appear that people’s minds can be changed. Maybe not everybody, but some people certainly do. The 71% of Americans who believe in climate change is a record high—it may be troubling that the number doesn’t match the 97% of climatologists who believe in climate change, but at least its moving in a positive direction.

As the founder of the Skeptic magazine, Michael Shermer makes his living debunking bad science and educating the public on scientific skepticism. Like any good skeptic, Shermer was initially uncertain of climate change, especially the idea that humans were its primary driver. But he changed his mind.

“What turned me around on the global warming issue was a convergence of evidence from numerous sources. […] Because we are primates with such visually dominant sensory systems, we need to see the evidence to believe it, and the striking visuals of countless graphs and charts, and especially the before-and-after photographs showing the disappearance of glaciers around the world, shocked me viscerally and knocked me out my skepticism.”

Richard Cizik, an evangelical reverend, also changed his mind after attending a climate change conference:

“I heard the evidence over four days, did a fist to the forehead and thought, ‘Oh my gosh, if this is true, everything has changed.’ […] I liken it to a religious conversion, and not just because I saw something I’d never seen before — I felt a deep sense of repentance.”

A Reddit thread titled ‘Former climate change deniers, what changed your mind?’ offered a variety of different reasons, including a sense of responsibility for the Earth (“I’d rather unnecessarily make the world a nice place to live than unintentionally contribute to making it less livable for many”), noticing weird weather (“Winters have been unusually warm, with flash major snow storms scattered throughout, and it’s gotten to the point where something just blatantly feels wrong about it”), and that climate change deniers don’t seem trustworthy (“I realized that many of the other people denying anthropogenic climate change were being funded by the fossil fuel industry”).

But the number one reason expressed in the Reddit thread and by the previous examples was a greater understanding of the science behind climate change. Michael Shermer is a skeptic, but skepticism requires paying attention to evidence. The Reverend Cizik attended a climatology conference. In the Reddit thread, 47% of responses attributed their change of mind to the evidence. As one Reddit user put it “… it’s just difficult for me to deny it with the overwhelming amount of scientific evidence that supports it. From what I’ve learned about the process it just makes too much sense to sound fake.”

The backfire effect

Based on the above, it seems like providing evidence is the best way to change minds. In an ideal world, evidence would change everybody’s mind, but its actually more complicated than that. The above sample has a selection bias—we only heard from people who have successfully changed their minds about climate change. It’s much harder to get a clear answer by asking “Climate change deniers, what would change your mind about climate change?”

Anybody who has ever gotten into a political argument is probably familiar with the backfire effect even if they didn’t know to call it that. Often, after hearing one factually inaccurate statement, somebody will provide a correction (“well, actually…”). This is referred to as the “information deficit model” of communication; the other side is misinformed, so you’ll provide a correction or further evidence they had lacked, and because the other side is a perfectly rational human being who are not under the sway of powerful emotions and beliefs central to their identity, they’ll change their mind. It may have worked for the people cited earlier, but it doesn’t work for everybody.

In fact, providing corrections and contrary evidence entrenches people in their beliefs: the backfire effect. Researchers have demonstrated this by showing study participants fake news articles that confirmed widespread misconceptions, like the idea that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction (WMDs). Then, researchers showed a true news article, like the fact that there was no evidence of WMDs in Iraq. For study participants who supported the Iraq war, seeing the second article made them believe there were WMDs more strongly than they had prior to starting the study.

The backfire effect isn’t the only bit of mental gymnastics we do when confronted with contrary evidence. Dr. Tali Sharot, a cognitive scientist, explains how people react to different kinds of evidence and how intelligent people are particularly susceptible to twisting facts in the video below:

Picking your target

So, providing facts—following the information deficit model—doesn’t always work. What does? In an article for Yale Climate Connections, Karin Kirk points out that often the most important aspect of persuading a climate change denier lies in picking the right target. She identifies six types of people when it comes to persuadability: the informed but idle, the uninformed, the misinformed, the party-line follower, the ideologue, and the troll.

Trolls

It will save you a lot of effort to understand the first lesson of the internet: Don’t feed the trolls. Trolls don’t debate somebody because they care about the topic. They care about the vitriol, the adrenaline, and “winning”. Your energy is wasted there.

Ideologues

It can be easy to feel equally frustrated when debating ideologuesand people who follow the party line. If the stakes were lower, leaving intractable people alone would likely be the best response, but reversing climate change will take broad support. Ideologues and followers of the party line, though, are highly susceptible to the backfire effect. Instead, take a parallel approach: Discuss the job growth that investing in green energy can provide, remark on how whichever nations don’t do so will be left behind in the future, describe how green energy essentially means free energy for all intents and purposes. Not everybody has to believe that climate change is real, and if we all work towards the same purposes for different reasons, what does it matter?

The misinformed

For the misinformed, it’s important to describe climate science in a conscientious way. Susan Hassol, the head of the nonprofit organization Climate Communication, says, “Good communication is a conversation, rather than a lecture.” Using the Socratic method—asking questions to test a debater’s underlying assumptions—can be a respectful way to expose a flawed understanding of a subject.

The uninformed

As for the uninformed, describing the broad, abstract, and globally catastrophic consequences of climate change isn’t likely to persuade them to learn more. They’ve already heard those angles. Instead, focusing on the personal impacts of climate change will be more effective. Will their children be able to enjoy the same climate they did growing up? Will the future economy help make them prosperous?

Informed but idle

The group we should focus on the most are the informed but idle. Often, these people fit into the 71% of Americans who do believe in climate change, they just don’t feel the urgency. Here’s where you can unleash your doom and gloom. Go nuts! Just don’t make it seem like nothing can be done. On the contrary, quite a bit can be done. Climate change is affecting everybody today, and there’s still time to make a difference. There’s certainly not enough time to permit easy and comfortable inaction, and often people simply lack the motivation. Climate change is nothing less than the complete and utter transformation of our society; if that doesn’t offer motivation, what else will?