The 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry winners all work with ‘directed’ evolution

Nobel Laureates in Chemistry, 2018. Credit: Niklas Elmehed/Royal Swedish Academy of Sceinces

- “Directed” evolution is a kind of coaxing, and speeding up of, evolution itself.

- The committee referred to the work of all three as “The foundation for a revolution in chemistry.”

- Frances H. Arnold is the fifth woman to win the prize in chemistry in its 117-year history.

How they did it

The 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry winners are Frances H. Arnold at the California Institute of Technology, Sir Greg Winter of the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in the U.K., and George P. Smith at the University of Missouri. They all used variants of existing chemistry studies to find solutions to problems such as creating biofuel from sugars, as well as altering human antibodies to fight things such as rheumatoid arthritis and cancer.

Arnold, only the fifth woman to win the prize in its 117-year history, won half of the prize, with Winter and Smith sharing the other half.

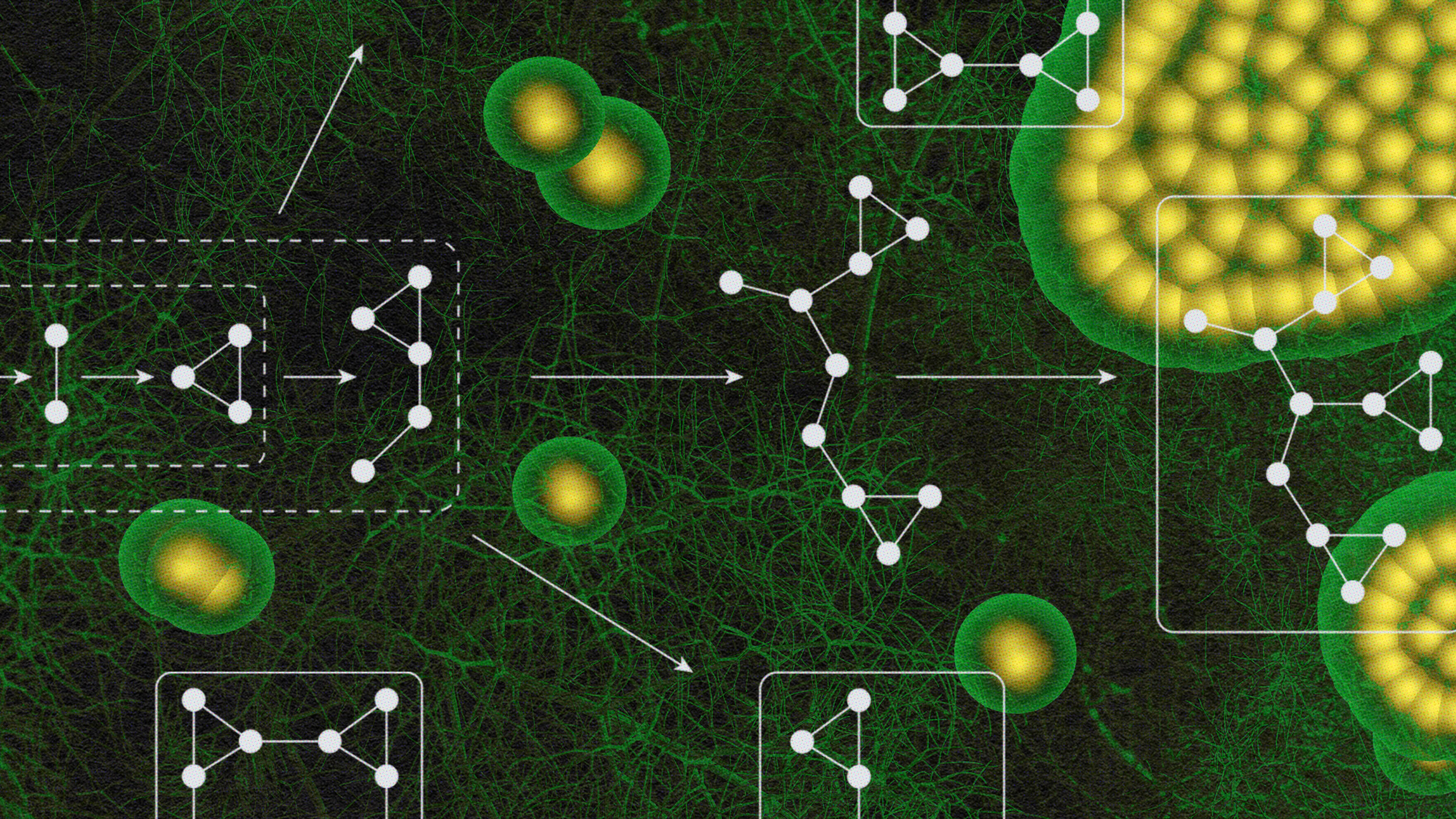

Analysis of CsoS1A and the protein shell of the Halothiobacillus neapolitanus carboxysome. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Coaxed mutation

Arnold flipped the entire idea that chemists had followed for decades on its head. Sort of.

You see, chemists before her spent lots of research and time trying to create enzymes that would perform things beneficial to humans, such as producing a drug that would be far too expensive to make in a factory.

This proved impossible; enzymes are far too complex to be harnessed like that.

Enter Ms. Arnold. She decided that by altering the genes that produce enzymes, via purposefully-introduced cell mutation that was even slightly closer to the desired results, eventually the cells produced would mutate again and again until they got to a desired point of behaving as she wanted them to.

Since she pioneered this technique in the 1990s and other scientists have followed suit, pharmaceuticals and even chemistries that didn’t exist previously have been successfully created via those enzymes. This has meant a reduction in harmful chemicals previously used to create similar effects, but critically, it’s also produced a fascinating possibility for future humans: biofuel, created from simple sugars into alcohol via mutated enzymes.

Arnold was asleep in a hotel room in Texas when her phone rang with the news, according to NPR.

“And at first, of course, I thought it was one of my sons, with a problem,” Arnold said. “But then it was a wonderful feeling. They told me that I had won the Nobel Prize!”

The cures that began as phages

Meanwhile, the second Nobel Prize winner, Sir George P. Smith, found a class of viruses called “phages,” which would actually invade bacteria and hijack their mechanisms. Greg Winter then built upon that work to alter antibodies, which are always on the lookout for foreign invaders in our bodies — specifically, proteins that are the building blocks of invaders such as viruses — and then “tagging” or marking those invader proteins so that other antibodies can collect and mass an attack.

Winter actually changed the genetics of those antibodies so that they’d instead seek the proteins that cause such things as rheumatoid arthritis. Other scientists then took that process and targeted diseases and viral attackers, such as lupus and anthrax. Alzheimer’s disease is quite possibly a future target for this, as is metastatic cancer.

Screencap from “Announcement of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2018” video below

By Nobel Prize Committee

“The greatest benefit to humankind”

The Nobel committee, in its announcement of the awards, summed it up: “The directed evolution of enzymes and the phage display of antibodies have allowed Frances Arnold, George Smith and Greg Winter to bring the greatest benefit to humankind and to lay the foundation for a revolution in chemistry.”