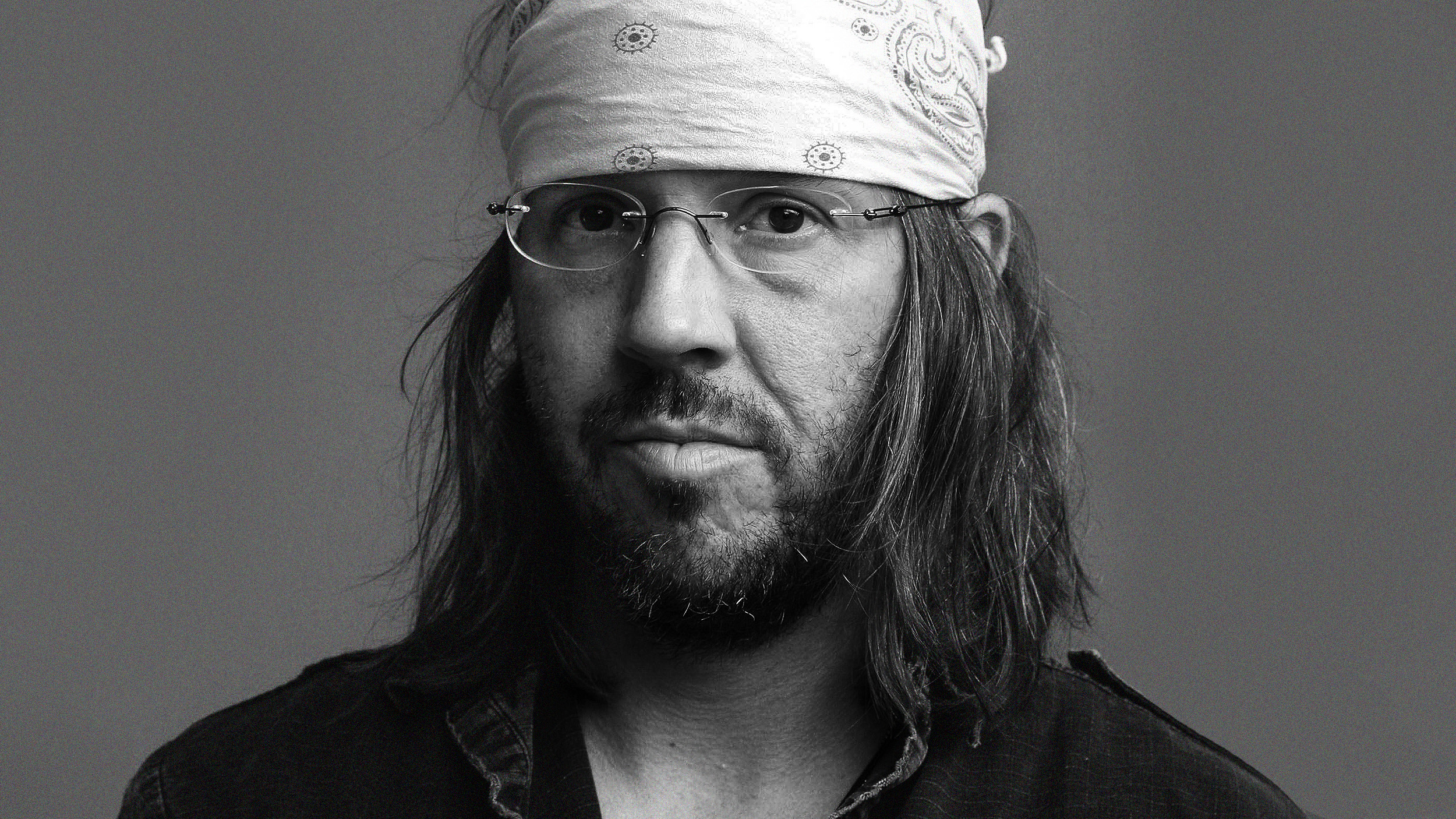

Write Like David Foster Wallace

John Jeremiah Sullivan has written a beautiful, beautiful piece about David Foster Wallace in GQ. It isn’t easy to write about Wallace; how Sullivan chooses to do it is illuminating. One hard part is writing about a writer who is no longer with us. Another hard part is writing about a writer who seemed hard-wired for doubt; as Sullivan puts it, he had a “sheer ability to consider a situation, to revolve it in his mental fingers like a jewel whose integrity he doubts.”

No one will ever write like Wallace. It will be in scale and subtlety of imitation that the imitators are marked, and discarded. But we can remember him for what we loved, and we can extract little lessons that force us to re-adjust our own bars.

On What Not To Worship, Wallace put it this way in his famous 2005 Kenyon Commencement Address:

“Look, the insidious thing about these forms of worship is not that they’re evil or sinful; it is that they are unconscious. They are default-settings. They’re the kind of worship you just gradually slip into, day after day, getting more and more selective about what you see and how you measure value without ever being fully aware that that’s what you’re doing. And the world will not discourage you from operating on your default-settings, because the world of men and money and power hums along quite nicely on the fuel of fear and contempt and frustration and craving and the worship of self. Our own present culture has harnessed these forces in ways that have yielded extraordinary wealth and comfort and personal freedom. The freedom to be lords of our own tiny skull-sized kingdoms, alone at the center of all creation. This kind of freedom has much to recommend it. But of course there are all different kinds of freedom, and the kind that is most precious you will not hear much talked about in the great outside world of winning and achieving and displaying. The really important kind of freedom involves attention, and awareness, and discipline, and effort, and being able truly to care about other people and to sacrifice for them, over and over, in myriad petty little unsexy ways, every day. That is real freedom. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default-setting, the “rat race” — the constant gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing.”

A speech doesn’t allow for classic tricks of Wallace’s prose, like footnotes. A speech demands something he likely loathed, performing. But the speech is worth reading as it illustrates what’s emblematic in Wallace: he looks at a thing closely. He elevates the banal, and infuses it with depth. Philosophers can stand in check out lines, too.

Wallace confronts a cliché (money doesn’t buy happiness). Then he highlights the confrontation, while confronting another cliché: that of a writer proposing that first cliché. Then he turns the confrontation of clichés into something unexpected: a rally, rather than a sermon; an idea of “freedom,” rather than a recipe for happiness. Finally, he reminds us that it isn’t easy. We suspect that, for him, nothing ever was.