Why Fallingwater Still Matters 75 Years Later

Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, especially in the arts. Paint, sculpt, or build it right and others will try to follow your path. That truth makes Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic home known as Fallingwater unique in that it has never been copied. “Fallingwater has no progeny,” Lynda Waggoner writes in Fallingwater, published to celebrate the 75th year of the home’s existence. “It is a singular work that appeared almost without warning, its legacy difficult to define.” Despite that difficulty, Waggoner and other essayists define the legacy of Fallingwater by looking back to its origin in 1936 and then looking forward to how Wright’s integration of artifice and nature continues to matter, maybe more now than ever.

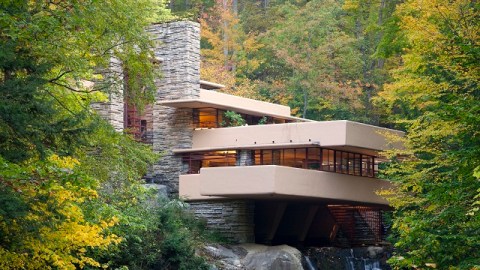

Wright built Fallingwater in 1936 for Edgar Kaufmann, Sr. and his wife Liliane, but the seeds of the progject were planted by Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., a student of Wright’s at Taliesin just a few years before. Set 50 miles southeast of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, partly over a waterfall on Bear Run stream near the Allegheny Mountains, Fallingwater is inseparably of its place, which probably makes it so hard to imitate. Waggoner, Fallingwater’s director and vice president of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy helping protect the landscape around the home, leads you on a private tour of the building and its environs. Acclaimed photographer Christopher Little, who worked on a previous tome on Fallingwater in 1986, returns to provide the perfect images for Waggoner’s words. The classic shots such as that from below the second falls (shown above) appear, of course, but pictures of the horizontally layered rock face of Pottsville sandstone above the stream clearly demonstrate how Wright found direct inspiration in nature, in this case to echo that layering in the very design of the house. When Little photographs the waterfall from the perspective of someone leaning over the west terrace and looking straight down into the waters, you’ll imagine you can hear the burbling stream. With Waggoner as your ears and Little as your eyes, reading the evocative text and flipping through the book’s breathtaking 250 illustrations is the next best thing to being there.

“Fallingwater reveals itself slowly,” Waggoner intones near the end of the tour. “Like a sculpture it must be viewed from all sides to be understood. There is no front or back; every elevation shows us another aspect of its nature.” This same slow reveal happens as you read the essays that follow Waggoner and Little’s opening tour. Neil Levine, the Emmet Blakeney Gleason Professor of History of Art and Architecture at Harvard, continues Waggoner’s idea by analyzing how Fallingwater exists in time as well as place. Walking around and within Fallingwater becomes a “temporal process of discovery,” Levine suggests, “where time is understood not merely in the literal terms of one’s movement through space in real time but also as a more profound sensation of the virtual time of duration.” In other words, even three quarters of a century later, Wright’s nature-based time machine moves as it stands still in the same way that nature itself does—the famous “woods decaying, never to be decayed”Wordsworth wrote of in the Simplon Pass. “In Fallingwater,” Levine concludes, “you do not ask where the house ends and the natural environment begins. Instead, you ask when—and the answer is never.”

In a similarly philosophical vein, Rick Darke examines the symbiosis between revolutionary home and edenic garden. “Wright began with an inventory of the existing natural features and gently edited, preserving all possible,” Drake writes. “He fit his architecture deftly into the landscape, respecting the site’s living character and ensuring that its dynamics would continue long after his work was completed.” Drake cites Wright’s love of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Transcendentalism as well as Wright’s Unitarian upbringing as sources for this reverence for nature. As John Reynolds, associate professor of architecture at Miami University of Ohio, points out in his essay, this reverence built into Fallingwater also translates into the same sustainability movement so crucial today, when we recognize just how deeply our ecosystem is in jeopardy. “Integrated intimately with nature,” Reynolds believes, “Fallingwater continues to point the way forward toward realizing a sustainable ethos in the way it allows us to dwell.” While Wright’s contemporary European architects such as Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe separated humanity and nature through their buildings, Reynolds argues, Wright, steeped in the American tradition of the Transcendentalists, fought against that modernist current and designed a home in rather than out of nature. Reading the essays and letters of the Kaufmann family, Fallingwater’s residents, provided in the book, you get a sense that they, too, believed in this union and provided Wright with the means and opportunity to realize his vision.

Fallingwater even provides its own cliffhanger, of sorts, with a happy ending. Ever since the supports were taken away in 1935, the master bedroom terrace has cracked and strained against the forces of gravity due to an error in design. In 2002, Robert Silman Associates finally found a solution that would save but not alter the building—a gravity-defying tale told by Robert Silman himself. As much as Fallingwater needs our protection and rescue, Fallingwater protects and rescues us from the threat of losing touch with the world around us. A multimedia experience far more mind-expanding than any on your iPad, Fallingwater reminds us that the real world of natural creation can inspire us to greater things simply by following its lead. If you follow the lead of Lynda Waggoner and Christopher Little’s Fallingwater, you’ll soon find yourself inspired to create and to conserve.

[Image: View of Fallingwater from below second falls. © Christopher Little from Fallingwater by Lynda Waggoner, Rizzoli 2011.]

[Many thanks to Rizzoli for providing me with the image above and a review copy of Fallingwater by Lynda Waggoner.]