Want to Be Happier? Recalibrating Your Expectations Might Help

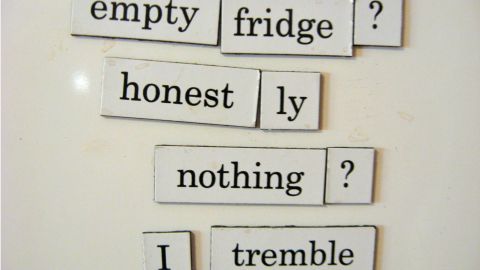

I’m hungry. I head to the fridge—but first, I shake my head and say mournfully to myself, there’s nothing to eat. I’m not looking forward to the process of choosing from what I know to be inferior choices. Imagine, then, my surprise when I open the door and see a plate of… it doesn’t actually matter what, as long as it’s (1) something I’m really in the mood for and (2) something I’ve completely forgotten about. How happy am I?

Now, picture the opposite: I’m hungry. I head to the fridge, full of keen anticipation. I know that the piece of cake that was left over from last night is still there, eagerly awaiting me in its full beauty on a perfect white plate. I open the door and see a plate of… nothing. Sometime between last night and this afternoon, someone else ate my cake. Who. Ate. My. Cake. I had it all pictured in my head—how I’d get it out, how I’d sink my fork into it, take the first bite, feel the wonderful crumbliness on my tongue—and now, my hopes have been shattered. How upset am I?

We hate to be disappointed—more than we enjoy being right

And here’s the real question: Am I happier when I find my surprising treat than I am upset at the lack of something I’d been awaiting? Is the opposite true? Or perhaps neither? Perhaps my happiness is more or less equal to my disappointment?

While the last option would seem to make a lot of sense—and indeed, when people are asked to predict their future affective, or emotional, state, it’s the one they tend to go with—the reality sides more often than not with option two: disappointment looms larger than pleasant surprise.

We’re notoriously bad at predicting our future feelings (if you’re interested in knowing just how bad, read any of Dan Gilbert’s work or watch his interview on Big Think). And one of the things that we’re especially bad at knowing is just how disappointed we’ll feel if something we’ve been anticipating doesn’t occur.

The key here is the negative mismatch between expectations and reality. It’s known as the contrast effect: people contrast what they thought would happen with what actually happened, and when the comparison is not favorable, satisfaction plummets (though if you’re generally an optimist, you’ll likely fare better). For instance, if you expect to enjoy a movie, but find it dull, you will be more unhappy than if you had no prior expectations at all. If you expect to find it dull but find yourself laughing instead, you will be more happy than if you’d already thought you were going to see a funny movie.

In the case of my cake in the fridge, in the first instance I had low expectations: nothing to eat. As a result, the contrast effect worked in my favor. My expectations were below the outcome, and so I was happier than I would have otherwise been. But in the second instance, the contrast effect worked against me. My expectations were too high, and so I was even more disappointed than I would have been absent any expectations at all. I don’t know if it’s because people are generally more pessimistic, or because we hate to be wrong, but the negative contrast effect is most always stronger than its positive counterpart.

Take note: that old business cliché about underpromising and overdelivering is very good advice indeed. But also remember its corollary: it’s not nearly as good as overpromising and underdelivering will be bad. Negative contrasts will hurt more than positive ones will help (though the latter are certainly quite welcome nevertheless).

Is this rational? Not really. The actual event is the same, no matter what. But the experience of the event differs substantially, and that does make a difference. We never come into a situation as a blank slate. We bring with us our goals, our expectancies, our past experiences. Indeed, for no two people will that walk to the fridge or that movie be the exact same. We are constantly comparing our current experiences to those in the past and recalibrating our expectations accordingly.

Think of it this way. If you live in Chicago, take a winter vacation to Miami, and upon arriving find yourself in the middle of a partly cloudy 70-degree day, you will likely be quite pleased indeed. After all, you’ve just come from the snow. Now, that same you at the end of the vacation, after a week of sunny days in the mid-80s, would likely be disappointed if your last day were to be the mirror image of the first: in that week, you’ve gotten used to a different point of comparison. Now, your expectations serve to make you upset. I can’t believe the weather is so miserable on our very last day!, you may well think. You no longer remember how happy that exact same weather made you seven days earlier.

How changing your point of comparison can help

But wouldn’t it serve you well to remember that the weather is still much, much better than what you’re returning to? It might take a little extra effort, but changing your point of comparison so that the reality falls in line with your expectations is a powerful mental trick. It can improve your enjoyment and your appreciation many times over. All it takes is a change of the frame of reference.

If I open the fridge and see the cake gone, I actually have two choices. Be frustrated, disappointed, and mad at the invisible culprit who stole my cake. Or, notice the wonderful pastry (or whatever it is) that still remains and focus on enjoying that instead. Forget the cake. I didn’t want it that much anyway. In fact, I am very happy for whomever it was that enjoyed it (ok, that might be a stretch – no need to go that far). But in any case, recalibrating my mindset will make the process much more enjoyable, and I can spend the time focusing on something that will make me happy instead of venting about something I can no longer change.

And on that note, I wish you all a happy Labor Day weekend. Only don’t expect it to be too happy – and chances are, you’ll end up happier than ever.

If you’d like to receive information on new posts and other updates, follow Maria on Twitter @mkonnikova

[photo credit: Bhakti Omwoods, Magnetic Fridge Poetry]