Treasure Hunters: Rediscovering George Inness’ Italian Sojourn

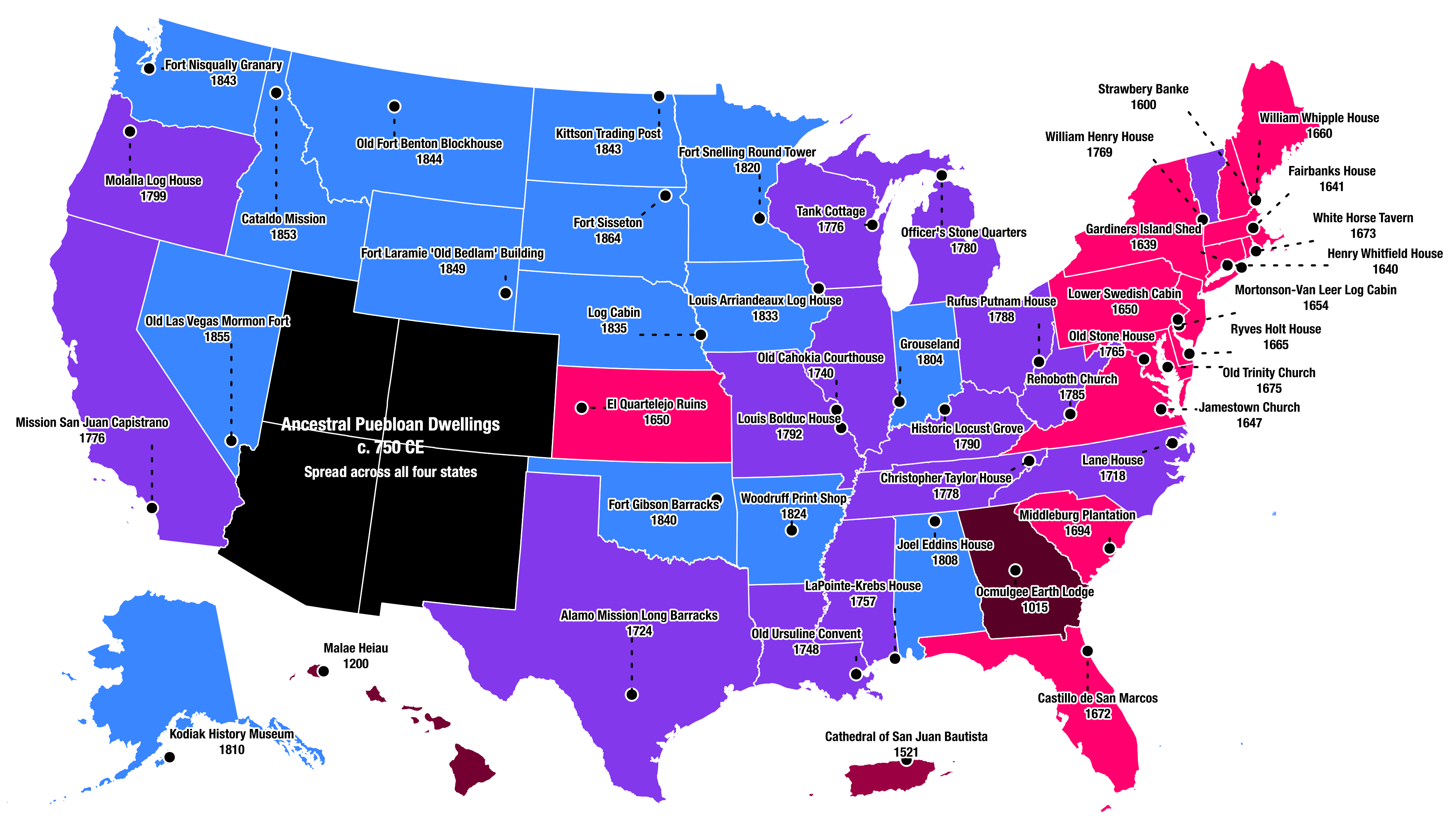

When Michael Quick searched high and low in 2007 for paintings by 19th century American master George Inness to include in what would be his award-winning catalogue raisonne of Inness’ work, he came to the Philadelphia Museum of Art to see Twilight on the Campagna. The 1851 painting had entered the collection in 1945 and hadn’t been exhibited since 1952. An example of Inness’ earliest work in excellent condition, Twilight on the Campagna was one of those hidden treasures languishing in the darkness for want of wall space, because of critical blind spots, or both. The PMA recognized the treasure in their basement and conserved this masterpiece, which is now the centerpiece of their exhibition George Inness in Italy, which runs through May 15, 2011. Ironically, Inness’ Twilight began with his own treasure hunting, specifically a sojourn to Italy in search of artistry of the past he could take and transform into a new type of painting for the future.

The show consists of only ten paintings, but they act as powerful points of reference for Inness’ development. Curator Mark Mitchell connects these dots beautifully in the catalog. Before leaving America for his first of two trips to Italy, Inness’ work showed the influence not only of the European Claude Lorrain, but also of Americans such as Thomas Cole and the Hudson River School. A pre-Italy work such as Classical Landscape, Mitchell explains, “exemplifies Inness’s pre-Italy aesthetics as well as his preconceptions of Europe shortly before his first visit there.” This pre-holiday snapshot captures Inness “plac[ing] less emphasis on narrative” than Cole did, while trying to imitate the “idealized pastoral subject, framing trees, darkened foreground interior, receding body of water, and atmospheric mountains in the distance” of Claude. Inness thus rejected the America he knew for the Europe of his imagination, which would soon be a reality.

“Italy was an enormous catalyst in Inness’s life, prompting him to engage fully with the scenes before him in a manner that was increasingly adventuresome, emotive, and poetic,” says Mitchell. “By working from direct observation, he channeled a romantic current in his paintings that made them less stylized and signaled his engagement with the scene before him as well as the Renaissance and Baroque masters to whom he looked for inspiration.” Inness actually traveled to Italy in 1851 (thanks to a generous patron) on an extended honeymoon with his new wife, already pregnant, but Italy soon became the love of his life. Direct exposure to the landscape of the old European masters inspired Inness to observe more closely, with Twilight on the Campagna being the finest result. “The painting’s elegiac tone, asymmetrical composition, emphasis on atmosphere, and absence of stock pastoral elements break with Inness’s approach up to this point,” Mitchell asserts. In a separate catalog essay by the painting’s conservator, Judy Dion, she describes and illustrates how infrared reflectography reveals Inness’ paring down of the trees on the right side of the painting “to intensify the austere drama… by simplifying their profiles.” Europe and Europe’s art teach Inness the art of visual editing in which less becomes more in a profound, spiritual sense.

Despite criticism that he leaned on the old masters too much, Inness retained them and their Europe in his head, heart, and eye upon his return to America in 1852. Using sketches, Inness continued to paint Italian works for years. A visit to France in 1853 introduces Inness to the Barbizon school of Corot, which he quickly added to the bubbling brew of influences. Inness returned to Italy in 1870 believing that he had left America behind for good. “As a place and a subject,” Mitchell claims, “Italy liberated Inness during and after his first trip there from the contemporary concerns of American nationalism and fickle popular taste.” Inness sought that same liberation again and again, yet always returned to America with hope for a better future. “Whereas the focus in Hudson River School painting was commonly on opposites in subject,” Mitchell proposes, “Inness focused on a formal opposition of the two dominant modes of landscape painting: dramatically sublime and serenely beautiful.” While Claude embodied the beautiful, Salvator Rosa stood for the sublime for Inness. With those two old masters as symbols of style, Inness found a new formula for creative tension driven by infinite aesthetics rather than finite storylines.

Thinking back in 1878 on his lifelong Italian treasure hunting, Inness thought of trees. “In Italy I remember frequently noticing the peculiar ideas that came to me from seeing odd-looking trees that had been used, or tortured or twisted—all telling something about humanity,” Inness said with his characteristic mix of specificity and mysticism. In George Inness in Italy, you can look at Inness’ once forgotten efforts to listen to that humanity and put it into wordless pictures. How wonderful to discover such magic before your eyes. How wonderful of the PMA to rediscover this masterpiece and its meaning hidden right beneath them. Seek such treasures and you shall find.

[Image:Twilight on the Campagna, c. 1851. George Inness, American, 1825-1894. Oil on canvas, 38 x 53 5/8 inches (96.5 x 136.2 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Alex Simpson, Jr., Collection, 1945.]

[Many thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for providing me with the image above and a review copy of the catalog to the exhibition George Inness in Italy, which runs through May 15, 2011.]