The Sacred Space of Libraries in Our Lives

Who gets to say who owns our libraries, and what are the risks embedded in making a library profit-driven? The New York Times choice to give Library Systems and Services (and their project to invest in local libraries) front-page space was adequate editorial force to forefront the question: is an American cultural, communal property’s value placed at risk if its ownership changes—or, more to the point in this case—if it has an owner? The good news: Americans care about their libraries. We need them, and we know it. This is why this story matters, and why we will watch how it evolves.

Here is the essential excerpt from the Times piece:

“There’s this American flag, apple pie thing about libraries,” said Frank A. Pezzanite, the outsourcing company’s chief executive. He has pledged to save $1 million a year in Santa Clarita, mainly by cutting overhead and replacing unionized employees. “Somehow they have been put in the category of a sacred organization.”

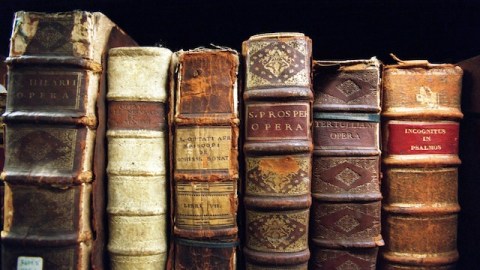

A sacred organization. This is happy news for libraries and librarians across the country, on the assumption that this view is shared. If it is shared, it means that even in this age of digitization, blog-ification, and iPads, there is a reason that local libraries continue to thrive and serve as necessary—or even, of schools: centers for their communities. The unions may balk, but it is not the union cry that is at the crux here. Rather, it is an idea of the place libraries hold in our lives, and the need to protect that idea.

While it would be too bold to propose libraries might take the place of churches, there is this parallel: we visit libraries to find quiet space, and room for reflections. We visit them to learn, and perhaps to create based on what we know and where we think we can contribute to what is not known. Increasingly, libraries are serving the space once filled by certain religious centers, or community centers: they provide peace, privacy, safety and opportunity. They are non-partisan pools for reflection, introspection, and observation.

Is observation undercut by the presence of a profit-motive? This argument is playing out in the schools right now and, while less contentious on many levels, it may next move into libraries, where the question remains: who owns these spaces, and what is the value of keeping the conceptually democratic ownership in place? Will it effect what the economists might call “the customer?” Will it affect the future? Maybe Davis Guggenheim’s next film will address America’s libraries: their history, their relevance, and our remaining need for them in our lives. Like schools, they are indivisible from local and federal government structures. Like schools, they have unique potential to evolve entrepreneurially, and apolitically. When it happens, as it happens, the world might even consider a uniquely American revolution.