Slavery Proponents Not Stupid, Excellent at Rationalizing Evil

“Secession wasn’t evidence that the South didn’t have a reasoned intellectual life. In fact, it was the strongest evidence that it did,” according to the teaser on a blog post by historian Michael O’Brien on the New York Times‘ website.

Historical evidence abounds that Southerners were not stupid or close–minded, let alone mad, but rather as capable of well-informed analysis as anyone else (though also as capable of making the wrong analysis).

If O’Brien’s point is simply that very intelligent and cultivated people can be very good at rationalizing evil, I agree wholeheartedly.

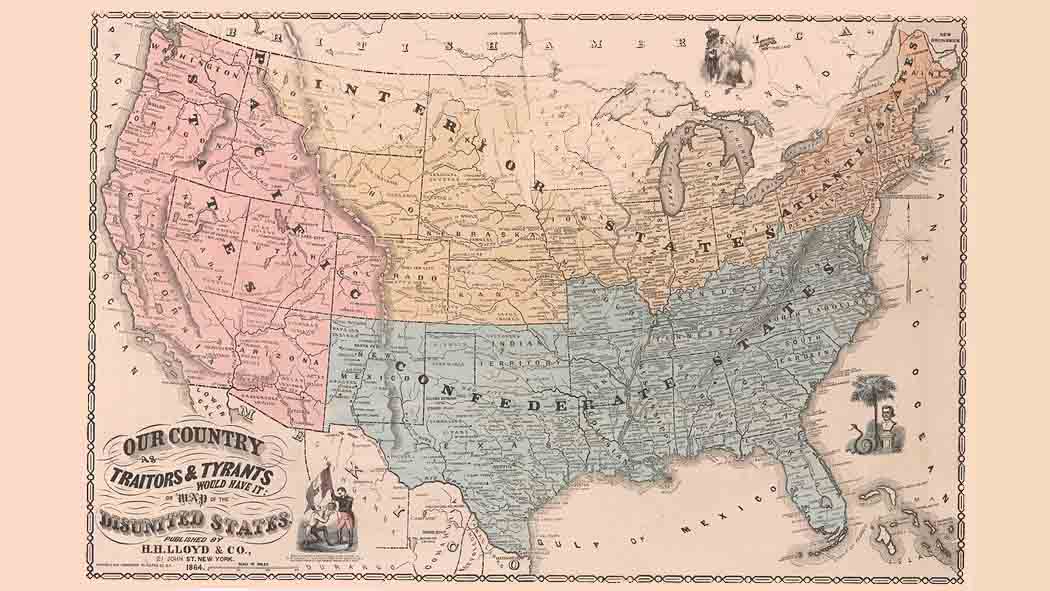

But to say that that the pro-secession, pro-slavery contingent was anything but close-minded is ridiculous. These people were so attached to slavery that they were willing to tear their own country apart and fight a bloody civil war to preserve their right to own other people.

O’Brien’s indulgence towards the cultivated pro-slavery contingent is odd because he isn’t one of those historians who soft pedals the centrality of slavery as a motive for the civil war. He doesn’t seem to be under any illusion that the pro-secession were motivated by anything more high-minded than preserving their own privilege:

Antebellum Southerners had often disagreed with one another, and secession was no exception. It is probable that, at least before the summer of 1861, more Southerners opposed secession than agreed with it. Despite this habit of dissent, however, a few ideas had focused debate on what it meant to be a Southerner. Slavery was seen as fundamental to social order, though opinion was divided about why. Almost everyone agreed that the Bible and Christianity sanctioned the institution, some thought its contribution to sustaining racial hierarchy was indispensable, and no one doubted that the Southern economy would be wrecked by the elimination of forced labor.

O’Brien goes on to talk about the different conceptions of the United States that enabled secessions to justify unilateral divorces and unionists to argue that leaving was not an option. “This was not just a difference of convenience, but a philosophical division about the nature of the state and time,” he writes. Fascinating.

But O’Brien already let the cat out of the bag when he conceded the centrality of slavery. Whether the Civil War was treason in defense of slavery or legal succession in defense of slavery is beside the point.

“Today Americans necessarily embrace the Unionist point of view of 1861, so that talk like Trescot and Davis’s gets branded as extremist and incoherent,” O’Brien writes. He’s a little coy about whether he’s talking about their views of federalism, or their views in general. Maybe their idea that the union was severable was on firmer legal and moral footing than their idea that whites could own blacks.

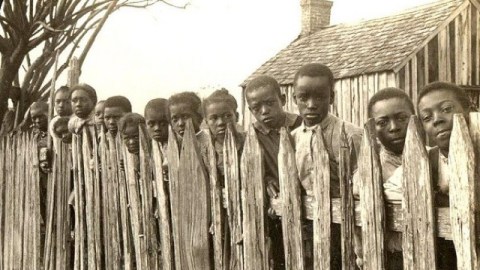

Jefferson Davis called slaves “that species of property on which our commercial prosperity depends, and the disturbance of which would involve us in total ruin.” O’Brien concludes by saying that:

This much is clear: far from being a case of the crazy South splitting from the wise North, in 1861 the balance of rationality and irrationality was poised. Both sides had a delicate mix of wisdom and folly, clarity and confusion, altruism and self–interest. Neither had a marked advantage when it came to rationality or madness.

Nobody thinks Jefferson Davis were stupid, or irrational, per se. As Davis pointed out, “slave property” was essential to the prosperity of people like him. With so much at stake, the best and brightest pro-slavery contingent came up with erudite-sounding arguments to justify why they were entitled to do what they wanted. When that didn’t work, they went to war.

O’Brien claims that secessionism was proof of the vital intellectual life of the South. He’s got it backwards. The South had a vibrant elite culture subsidized by slave labor. When their caste’s supremacy was challenged, many of these cultivated white moneyed intellectuals got busy explaining why they deserved a lifestyle underwritten by human bondage.

[Photo: From a series of photos of slaves and former slaves, posted by Okinawa Soba, Creative Commons.]