READING: Julian Barnes, Loss, and Literary Cliche

Thinking about revolutions is inextricable from thinking about grief. We cannot know how many lives will be lost, but we know that those left behind will engage in personal and communal, grief. The “memoir of loss” is a popular genre, but what teaches us more: personal experiences of others, or science telling us how to feel, how long to feel it—and why.

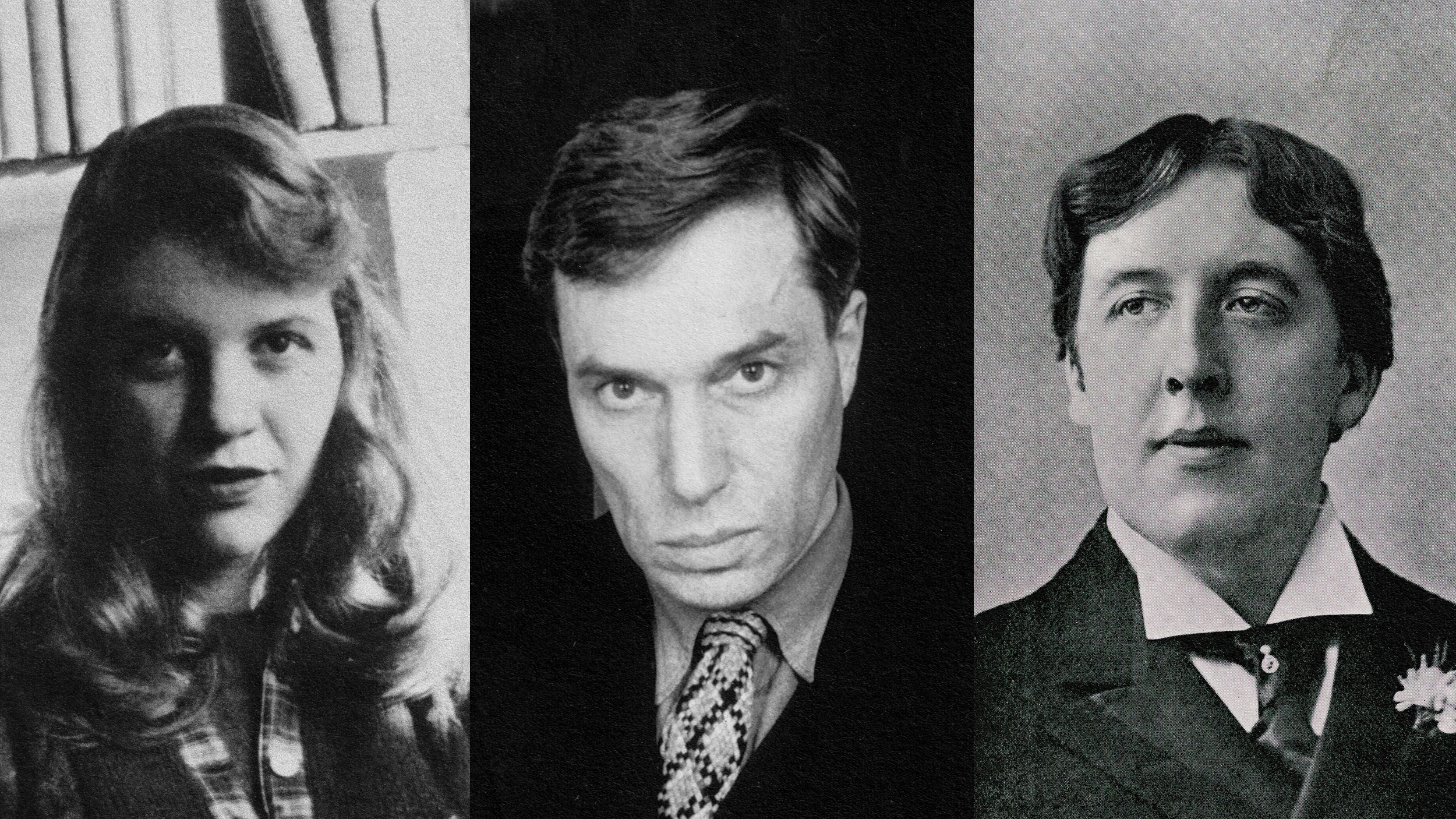

English novelist Julian Barnes, in reviewing Joyce Carol Oates’s new memoir, A Widow’s Story, in The New York Review of Books,draws a parallel between Oates’s book, and Joan Didion’s Year of Magical Thinking, two works from which we can learn a lot about loss. But Barnes addresses the difference in styles:

Oates’s book is largely based on diary entries, most from the earliest part of her year: so in a 415-page book, we find that by page 125 we have covered just a week of her widowhood, and by page 325 are still only at week eight. While both books are autobiographies, Didion is essayistic and concise, seeking external points of comparison, trying to set her case in some wider context. Oates is novelistic and expansive, switching between first and third persons, seeking (not with unfailing success) to objectify herself as “the widow”; and though she occasionally reaches for the handholds of Pascal, Nietzsche, Emily Dickinson, Richard Crashaw, and William Carlos Williams, she is mainly focused on the dark interiors, the psycho-chaos of grief. Each writer, in other words, is playing to her strengths.

And so we all do. The runner might increase her daily mileage after loss, or the surgeon the length of his rotation. It’s no accident that writers turn to words. But Barnes is first in making a concrete, critical connection between the styles these two women chose when writing about grief, and the styles they have lived their literary lives within, styles inimitably theirs even as generations of writers have ached to crib them. A comparison of the two books’ styles is an excellent, non-scientific metaphor for the urge to compare losses in general. Grief has a style. Loss has a style. And that style has its challenges. Barnes continues:

In some ways, autobiographical accounts of grief are unfalsifiable, and therefore unreviewable by any normal criteria. The book is repetitive? So is grief. The book is obsessive? So is grief. The book is at times incoherent? So is grief. Phrases like “Friends have been wonderful inviting me to their homes” are platitudes; but grief is filled with platitudes. The chapter headed “Fury!” begins:

“Then suddenly, I am so angry.

I am so very very angry, I am furious.

I am sick with fury, like a wounded animal.”

If a creative writing student turned this in as part of a story, the professor might reach for her red pencil; but if that same professor is writing a stream-of-consciousness diary about grief, the paragraph becomes strangely validated. This is how it feels, and what is grief at times but a car crash of cliché?

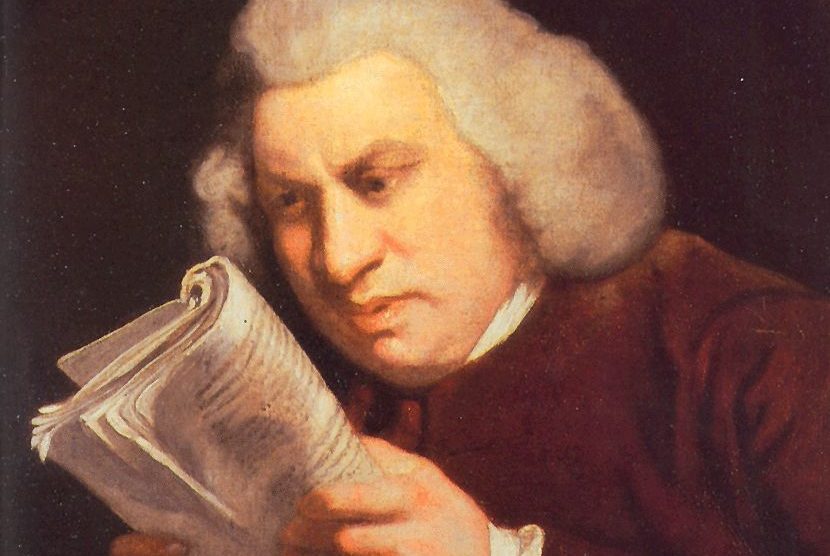

And this is why it’s perhaps beside the point to critically appraise memoirs of loss. We will need to read them (the good ones) for as long as we will need to write them. Unlike therapy, or pills, great books are cheap. What we learn from stories of loss is—back to Barnes’s—that grief, like DNA, is unique. What protects us is also unique, and even genetic: how resilient are we; what does life bring in the months after? And then there is time. Data shows, it heals. Barnes quotes Dr. Johnson on loss: “the continuity of being is lacerated.” This may be the most elegant description of all, but Johnson waited twenty-eight years after losing his wife to write it.