More on the issue of forced treatment

A number of responses to my post on mental illness and civil rights deserve some further thought.

A number of people have pointed to the variance in definitions of mental illness over the decades, and asked: Why should doctors be able to require you to assent to a concept of mental illness that they themselves may drop in the next edition of the DSM? Rachel Aviv’s New Yorker piece made a similar case.

I think this argument is a bit beside the point. The important distinction isn’t between this year’s theory of schizophrenia and 1970’s; it’s between some kind of treatment and none. I assume that 8 times out of 10, some kind of treatment will be better than none—if only to bring people in out of the rain, and get them the attention of professional healers. Saying that someone should get state-of-the-art help does not commit one to the notion that the state-of-the-art will never change, and cannot be improved. Any given decade’s notions of mental illness are indeed problematic. But they are better than nothing.

Rather than inaccurately insisting that psychiatrists have or will ever agree on the right treatment, why couldn’t the law simply distinguish among levels of intrusiveness? Regulations could make it relatively easy to force someone to come in from the cold, to eat, and to be clean. And relatively easy to force someone to engage in talk therapy. The threshold for forcible medication could be higher. And the threshold for treatments that have permanent debilitating effects—electroshock, for example—could be much higher still. These gradations could be defined by statute without any commitment to the notion that they reflect the final, absolute and certain truth about mental illness.

Other commenters mentioned the stigma of mental illness, and our tendency to essentialize it—where we see a person suffering now from psychosis, we tend to think we are seeing “a psychotic,” a person defined entirely and only by their mental troubles. Among the many bad effects of such stereotyping, according to a forthcoming study to be published in the June Social Psychology Quarterly, is that it worsens sufferers’ symptoms: In the study, adult schizophrenics whose mothers saw them as incompetent and unpredictable had worse symptoms than those whose mothers saw them more positively.

The need to guard against such prejudices has been well described in Refusing Care, Elyn R. Saks’ book on these issues (which shows her views to be much more nuanced than could be represented in a few lines in Aviv’s piece). As Saks points out, there is a concrete way to measure stigma: The sheer absence of facilities for treatment and care in the U.S. Oxford in the United Kingdom and New Haven, Connecticut are both university towns with roughly the same number of inhabitants, she notes in the book. Yet Oxford has many clinics where a mentally ill person can get help. New Haven has one.

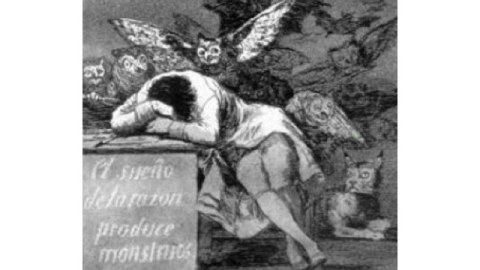

Third, some rightly bring up a concern for “neurodiversity.” A power to compel treatment is a power that can be abused. It can be directed at neural and sexual minorities, defiers of convention, nonconformists, political dissidents and other people whose freedom annoys some interests but doesn’t threaten society. You needn’t look far for horror stories—Soviet dissidents in mental hospitals, for example, or this psychiatrist. This is a legitimate worry. But the potential misuse of state power is not an argument for anarchy, because the potential harm of abdication could be worse. Anyone who has seen it at close range can tell you that psychosis isn’t eccentricity; it isn’t an alternate way of being human, with its own pluses and minuses; it isn’t a wild way of acting that disturbs the narrow-minded. Psychosis is pain, anguish and exile from human society. The subject of Aviv’s article starved herself to death.

Finally, there’s the elephant in the hall of medical ethics, that no one likes to talk about: Money. Megan McArdle hit this issue on the head on Tuesday, in this post. It was prompted by the New York Times’ series on the vast holes in New York State’s safety net for developmentally disabled people. But, as she wrote, her point applies to facilities that care for the elderly. And, I think, it also applies to the treatment of the mentally ill.

And her point is this: “When you see some unconscionable abuse and ask `Why?’ the answer is usually green, and it folds. Sometimes it’s personal venality. But sometimes policymakers are just trapped in a web of very bad choices: limited resources and unlimited wants.” It’s easy to call for more and better care for the vulnerable. But how much better are we willing to make it, before we start to notice the laid-off teachers and firefighters and shuttered libraries and say, wait a second?

On this point, psychosis creates a vicious cycle indeed: Like other primates, we human beings get through life by making friends and allies. This capacity for coalition-building is one of the things psychosis breaks.

We help our friends; they help us. Kids will take part in this give-and-take in the future; old people did their part in the past. By such imagery are we persuaded to aid the vulnerable and afflicted. But the mentally ill are cut off from that natural system of exchanges. McArdle puts it in practical terms: “I doubt many politicians are going to shaft the firefighters to take care of people who will never vote.”

The money squeeze means it’s possible that my assumption about treatment, at times, will be wrong: There will be times when forcing someone into available treatment really would leave them worse off than they would have been if left alone. But surely that just makes it more important, not less, that some of the people involved in the choice are not delusional.