Is Dura-Europos the Missing Link of Ancient Art History?

By the time the Persians destroyed the Roman military garrison at Dura-Europos in 256 AD, the city high above the Euphrates River existed for almost six centuries since its founding by one of Alexander the Great’s generals. A cosmopolitan city standing between Syria and Mesopotamia and, therefore, at the crossroads of politics, commerce, cultures, and religions between the Mediterranean and the Near East, Dura-Europos disappeared from view, buried by time until rediscovered in 1920. In Edge of Empires: Pagans, Jews, and Christians at Roman Dura-Europos, which through January 8, 2012 at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, that city lives again and offers a snapshot of how the people in that time and place viewed their world and themselves. The art of Dura-Europos, sometimes called “Durene Art,” fills in an important “missing link” of art history—the elusive time known as Late Antiquity, or the gap from the third to the seventh centuries when Classical Antiquity disappeared and the Middle Ages, formerly known as the “Dark Ages,” emerged. By shedding light on how the glory of Rome faded into the shadows of the murky Middle Ages, Edge of Empires provides the final piece of a long-incomplete puzzle.

“This was a polyglot city, where Aramaic and Parthian could be heard alongside the Latin of the Roman legionaries and the Greek of the Roman imperial administration,” G.W. Bowersock writes in the introduction to the exhibition catalog. Abandoned after the Persian onslaught, Dura-Europos soon slept silently beneath the sands of time. Reawakened after World War I, the city amazed its discoverers with its fresco-filled synagogue, early Christian chapel, shrines and temples to the old gods, and lavish home of the Roman commander, complete with picturesque view of the Euphrates below. Dura-Europos captures a moment when all the faiths—old and new—coexisted in relative peace, just before the Middle Ages’ ceaseless contest for souls plunged the Western world into darkness.

Thelma K. Thomas of New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts explains Dura-Europos’ significance in art history. Calling its vast spectrum of religious art and architecture “unparalleled,” Thomas believes that this bounty comes from a trend “characteristic of Late Antique culture across Eurasia: the stagy display of material wealth in self-presentation.” These people wanted to be known in their own time and adopted or adapted styles from every corner of the Roman Empire (and beyond) to tell their story. In addition to the Jewish, Christian, and Middle Eastern touches, elements of Celtic, Persian, and even Chinese art and culture found a home in the remote outpost at the edge of the empire.

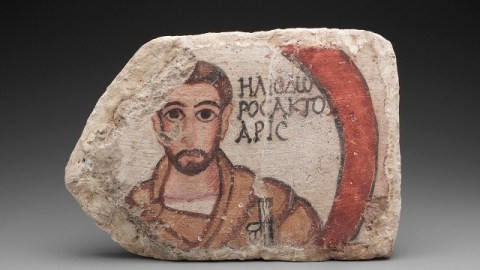

Thomas doesn’t see a unified statement in Durene art. Instead, she sees representations of a community built up over time. A portrait of an elite family from the second century after Christ brings them to life again. A Roman tribune and commander chooses to be depicted with his soldiers while sacrificing to the male gods—a macho image for the ages. Thomas remarks on how some figures “turn from the sacrifice to face front and look through the ‘window’ of their pictorial space, as if to address their audience, members of their religious community.” This caught-in-the-act quality makes portraits such as that of Heliodoros (shown above), who worked as an Actuarius or Roman accountant of sorts, come alive not only with the freshness of their colors but with the clear humanity of their depictions. The people of Dura-Europos wanted to look up at the walls around them and remember earlier generations just as we look at them today: not just out of random curiosity but from a deep desire to see something of ourselves there.

“In the future, much more might be learned from Dura-Europos about the importance of military and frontier encounters for the arts of Late Antiquity,” Thomas concludes. Clearly, the Greco-Roman gods wrestled with the Judeo-Christian divinity in Late Antiquity Rome and its outposts, but, because the expanded reach of the Roman Empire allowed soldiers to travel far and wide and bring back home elements of Celtic, Chinese, Middle Eastern, and other cultures with them, we must widen our own horizons to see those “new” influences from millennia ago. By coining the term “Durene Art,” Thomas and others created a unique label before other labels could diminish the impact of this amazing find. With a true openness to discovery and amazing scholarship and passion, Edge of Empires: Pagans, Jews, and Christians at Roman Dura-Europos shows us the face of a forgotten past preserved in art and architecture while simultaneously teaching how profound darkness can come out of an intolerance bred when diversity is denied.

[Image: Ceiling Tile with Portrait of Heliodoros, an Actuarius (Roman Fiscal Official). Clay, with a Layer of Painted Plaster, H. 30.5 cm, W. 44.0 cm, D. 6.7 cm. From the House of the Scribes, Dura-Europos, 200–256 CE. Yale University Art Gallery, Yale-French Excavations at Dura-Europos: 1933.292. Photography © 2011 Yale University Art Gallery.]

[Many thanks to the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World for providing me with the image above from and a review copy of the catalog to Edge of Empires: Pagans, Jews, and Christians at Roman Dura-Europos, which runs from September 23, 2011 through January 8, 2012.]