How One Chinese Scroll Painting Is Like a Celebrity Sex Tape (With a Commentary Track!)

The celebrity sex tape seems to be a modern phenomenon, but long before voyeurs could download the peccadilloes of Paris and Pam there was The Night Banquet of Han Xizai. A landmark of Chinese scroll painting, The Night Banquet tells the sordid story of a political advisor to the emperor. In The Night Banquet: A Chinese Scroll through Time, De-nin D. Lee not only delves into the juicy details of the painting itself, but also explains how the stamps and text added by owners of the scroll over the centuries don’t deface the work (as Westerners would think) but, instead, add to the experience—as if the “sex tape” came with its own “commentary track.” Lee’s commentary brings both the banquet itself back to life and all those who have taken a peek at the proceedings since that long-ago dynasty.

Lee, assistant professor of art history and Asian studies at Bowdoin College in Maine, begins by bemoaning the practice of scrubbing such marks from Chinese art. “A Chinese painting, especially a handscroll painting without its complement of textual accretions, loses, quite literally, its history,” Lee explains. Imagine if everything every owner of a Rembrandt painting thought about it were somehow appended to the canvas and you begin to understand the symbiotic relationship between Chinese painting and these marks. “Embedded in the impressions of imperial and private collectors’ seals, and woven into the inscriptions and colophons—the poetic and prose texts that precede and follow the painting proper—are estimations of artistic merit, to be sure,” Lee writes, “but also bits of family lore, moralizing pronouncements, partisan politicking, bureaucratic operations, clandestine communications, and artful self-promotion.” This “repository” of the painting’s “long and complex cultural life” builds a bridge between the past and today by linking us with those who have thought about (and brought their own agendas) to the painting as much as we do now.

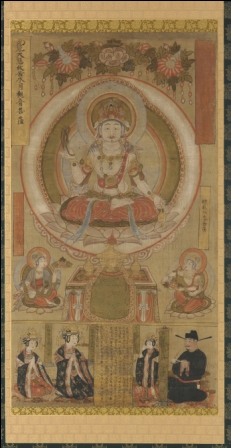

The legend behind the painting goes like this: Emperor Li Yu of the Southern Tang Dynasty grew worried over reports of the hard-partying lifestyle of one of his advisors, Han Xizai. Han allegedly hosted wild parties featuring wine, women, and song stretching long into the night. Faced with the fact that video hadn’t been invented yet, the Emperor instead sent artist Gu Hongzhong to peek in and portray Han in the act. Han and his guests appear in several scenes with courtesans playing music and enticing men to greater pleasure. The most infamous passage (shown above) has a disheveled Han, lady friend at his side, speaking with his guests with rumpled bedclothes seen in the background to suggest what just occurred. Thus, the scroll painting known as The Night Banquet of Han Xizai was born. Or was it? Most scholars now believe that the scroll we now have is actually either a copy of the original because the earliest stamp belongs to Emperor Gaozong of the 12th-century Song Dynasty or perhaps a total fabrication based solely on the legend of a lost original. Either way, the long history of the scroll itself provides a neat history of Chinese art and society in a nutshell.

Lee uses the idea of Gu Hongzhong’s original voyeuristic act as a springboard for further consideration of the scroll. “In the course of seeing the handscroll painting,” Lee argues, “the viewer’s psychological state oscillates between anticipation and desire to see what is yet hidden and satisfaction and pleasure at what has been revealed.” If we could only experience the scroll as it was meant to be seen—rolled out scene by scene, almost cinematically—we would replay that first voyeuristic act thanks to the medium itself. (You can read the scroll virtually here.) She goes on to contrast the Confucian gaze versus the voyeuristic gaze inspired by The Night Banquet. This Confucian gaze “uses a moral lens to seek ethical exemplars,” according to Lee, and pervades much of the textual commentary tradition of tut-tutting Han’s bad behavior. The voyeuristic gaze, however, enjoys the show and almost participates in the revels, lording over the scene as the artist and the Emperor originally did. A third type of gaze, the connoisseurial, combines the first two while adding the ego of the collector. Through this connoisseurial gaze, the owner “appropriat[es the scroll] as a vehicle to project desirable images of themselves as upright albeit misunderstood officials or as well-rounded statesmen,” Lee believes. Han’s immortalized infamy fuels the owners’ self-aggrandizement and fame by association with the work. “As long as the painting circulates and endures,” Lee writes of these connoisseurs with agendas, “so do their words.”

These connoisseurs comprise a fascinating cast of characters. The 18th-century Emperor Qianlong, instead of adding his comments to those that appeared before, put his at the front, stealing the show before it even begins. Qianlong scattered his seals throughout the document, marking it as his territory like no one before or since. Lee calls these seals “documentary in nature”—a permanent record that the Emperor was here, and here, and here, many, many times. Artist Ye Gongchuo adds the last commentary in 1947 when the owner, fellow artist and neighbor Zhang Daqian, lent the scroll to him for ten days. Ye surveys all that had been written before but resists the urge to offer a final, definitive word. Instead, the artist Ye leaves questions unanswered that the artist Gu Hongzhong first posed. Ye even gives poor Han some faint praise.

De-nin D. Lee’sThe Night Banquet: A Chinese Scroll through Time complements Michael Sullivan’s earlier The Night Entertainments of Han Xizai: A Scroll by Gu Hongzhong (which I reviewed here) and adds valuable insight into the psychology of the scroll painting with her Lacanian-influenced use of the gaze. Lee sets out a template for non-experts to see Chinese scroll paintings as both works of the past and living documents of all that has transpired since. Han Xizai’s centuries old “sex tape” continues to draw our interest, but as Lee proves, it’s the commentary that holds the real message.

[Many thanks to the University of Washington Press for providing me with a review copy of De-nin D. Lee’s The Night Banquet: A Chinese Scroll through Time.]