Full House: Cezanne’s Card Players at the Met

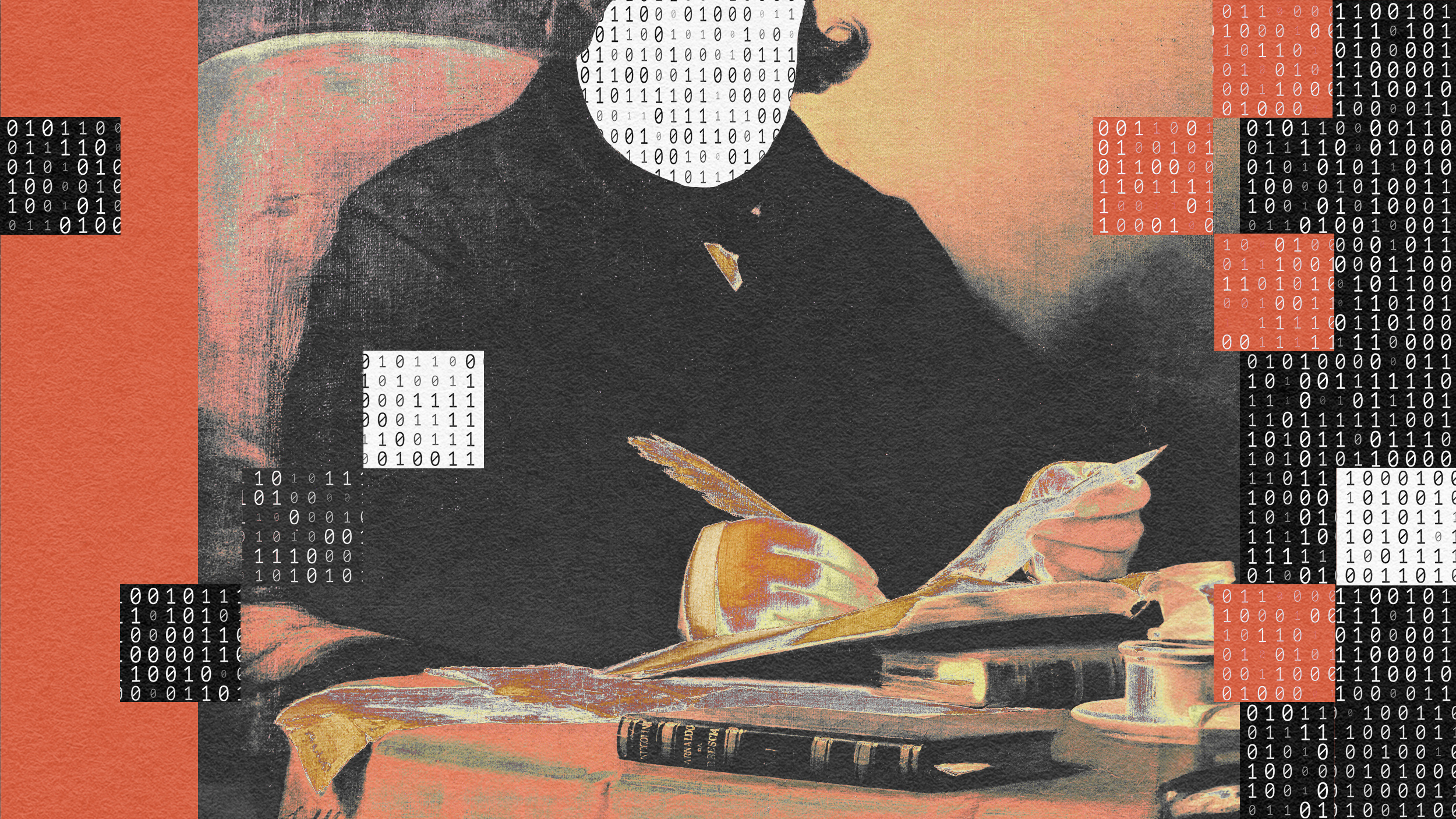

Paul Cézanne painted slowly. Very slowly. The fruit in his still lives would ripen and even rot as he worked. Hortense, first his mistress and later his wife, visibly suffers in his portraits of her (although some of that may be due to their difficult union). Cézanne’s father agree to pose only if he could read a newspaper, which the painter impishly changed from the conservative paper his father favored to a radical rag. Only Mont Sainte-Victoire provided the perfectly patient subject. But before Cézanne met his mountain, he looked outside his immediate family to the “extended” family of his father’s employees on their estate just outside Aix-en-Provence. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York brings together Cézanne’s paintings featuring his favorite setting for those workers—playing cards. Cézanne’s Card Players, which runs through May 8, 2011, brings the “full house” of this subject and invites us to join in the game of painting Cézanne played through these players.

The exhibit, which appeared first at The Courtauld Gallery in London (owner of one of the five versions of The Card Players in existence), is conspicuous by its size, or lack of it. Just 12 paintings and 8 drawings tell the story of how Cézanne developed this subject. Of the five versions of the subject around the world, only three appear here (including the Met’s own version, shown above). The missing versions in Russia and at The Barnes Foundation would have added to the effect, but probably not by that much. (The Barnes ruined a similar reunion of Cézanne’s Large Bathers in 2009 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s Cezanne and Beyond extravaganza, but at least the missing member was just a short drive away.) The focus of the show is more about how Cézanne, the painstaking perfectionist, assembled these group portraits.

Faced with the impossibility of getting all these men to sit for that long together, Cézanne made the concession of painting them one at a time and created an uncharacteristic, for him, composite portrait. Some of those preliminary individual studies appear in the show. “Preliminary” studies of a different sort appear in an introductory section featuring engravings after Chardin, Caravaggio, and others depicting card players over time—from card sharps to outright cheats. Cézanne haunted the Louvre as a young man and copied the masters he found there, so the weight of art history laid heavily on his mind.

Yet, as old as the genre of card games may seem, Cézanne still seems to bring something new to the table. Where Chardin or Caravaggio can seem playful, light, or even naughty, Cézanne seems none of those things. His players seem ponderous, concentrating with an intensity seen more frequently in chess than in games of chance. The mental energy of playing the hand dealt to them mirrors the mental energy Cézanne invests in the picture as he plays the hand of shapes and colors dealt to him by nature. The result is a full house of Cézanne’s masterful technique in action, which always means a kind of inaction. “I love above all else the appearance of people who have grown old without breaking with old customs,” Cézanne once said. These card players have the timelessness of men seeking entertainment the way that their fathers and grandfathers once did. Yet, Cézanne painted them by breaking the “old customs” of painting and ushering in a new way of seeing that would evolve into Cubism, the beginning of the modern art movement parade. Cézanne’s Card Players may be small, but it speaks in the language of mountains, even if the mountains are simple men seeking a moment of leisure. Cézanne’s “full house” extended to these men, some of whom he knew from childhood, and brought an egalitarianism to what could have been a chilled, elitist, intellectualized game.

[Image: Paul Cézanne (French, Aix-en-Provence 1839–1906 Aix-en-Provence). The Card Players, 1890–1892. Oil on canvas. 25 3/4 x 32 1/4 in. (65.4 x 81.9 cm). Bequest of Stephen C. Clark, 1960. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.]