Fanatical Devotion: Where Have All the Passionate Artists Gone?

Amongst the weaponry of the Spanish Inquisition were such diverse elements as fear, surprise, ruthless efficiency, and an almost fanatical devotion to the Pope, or at least that’s how the Monty Python sketch put it. Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition’s level of fanaticism when it comes to art today, but Andrew Baker in a recent issue of The Atlantic thinks it should. After taking a stroll through The Cloisters in New York City with a friend, Baker came away thinking that what today’s art needs is some of that old time religion—a passionate devotion “[n]ot to God, but to the work itself,” Baker writes. Baker raises a good question about the seeming indifferent cool of contemporary art, but I think his inquisition of all contemporary art is just as misguided as the one the Pythons spoofed.

Baker and friend begin their stroll through The Cloiseters “with thoughts of the Biennial and of the emptiness of its brand of celebrity still fresh in our minds.” Looking at the medieval art and artifacts, they soon were “struck by the scale” of even the smallest objects, which bore “more weight than anything I’d seen in I-don’t-know-how-long. And what was this weight? Whatever it was, it seemed to flow through those halls like lava: dense and slow, but hotter than you can imagine. And it filled those spaces with a power to preserve the old as new, and leave the new cowering in shame and in awe.” After some more beautiful passages of writing, Baker and friend finally conclude that this “weight” was “more than skill, technique, or inspiration.” Instead, he felt an almost electric “current that reverberated through the halls of that abbey and those of so many of the great museums of the world, yet so few of the places where new art is still being made and shown is nothing if not the lingering vibration of the profound and unshakeable devotion of the makers. Not to God, but to the work itself.”

In a nutshell, the juice found in medieval art was perhaps squeezed out thanks to religious fervor, but only as a complement to the artist’s love of art making. Today’s artists, in Baker’s view, simply don’t have the same electric force conducting through the work to the viewer. I both agree and disagree with Baker. I agree that Biennial’s tend to be tepid affairs with the usual suspects patting one another in a vicious circle of mutual aggrandizement. To condemn contemporary art on such counts is fair to a point, but such statements assume that Biennials truly represent contemporary art, which I don’t think they do. Just as the Salons once excluded the revolutionary Impressionists in 19th century France, the real revolutionaries—the true acolytes of the religion of art—often toil in obscurity today.

For example, perhaps one of the most religiously devout artists ever—Vincent Van Gogh—remained a “painter’s painter” (that is, the classic starving artist) throughout the 1880s. Baker could have just as easily written his piece in 1880s France, blissfully oblivious to the passionate genius around the corner. What present passionate geniuses await discovery (perhaps posthumously)? Just because we don’t know them now, doesn’t mean that they don’t exist. The most passionate artists often challenge the status quo. The price of subverting the system is usually martyrdom and the agony of watching establishment artists enjoy the financial spoils. With Lynn Hershman Leeson’s documentary !Women Art Revolution still fresh in my mind (my review here), I can think of countless women artists working in obscurity for decades with no reward other than the satisfaction of expressing themselves in art despite long odds.

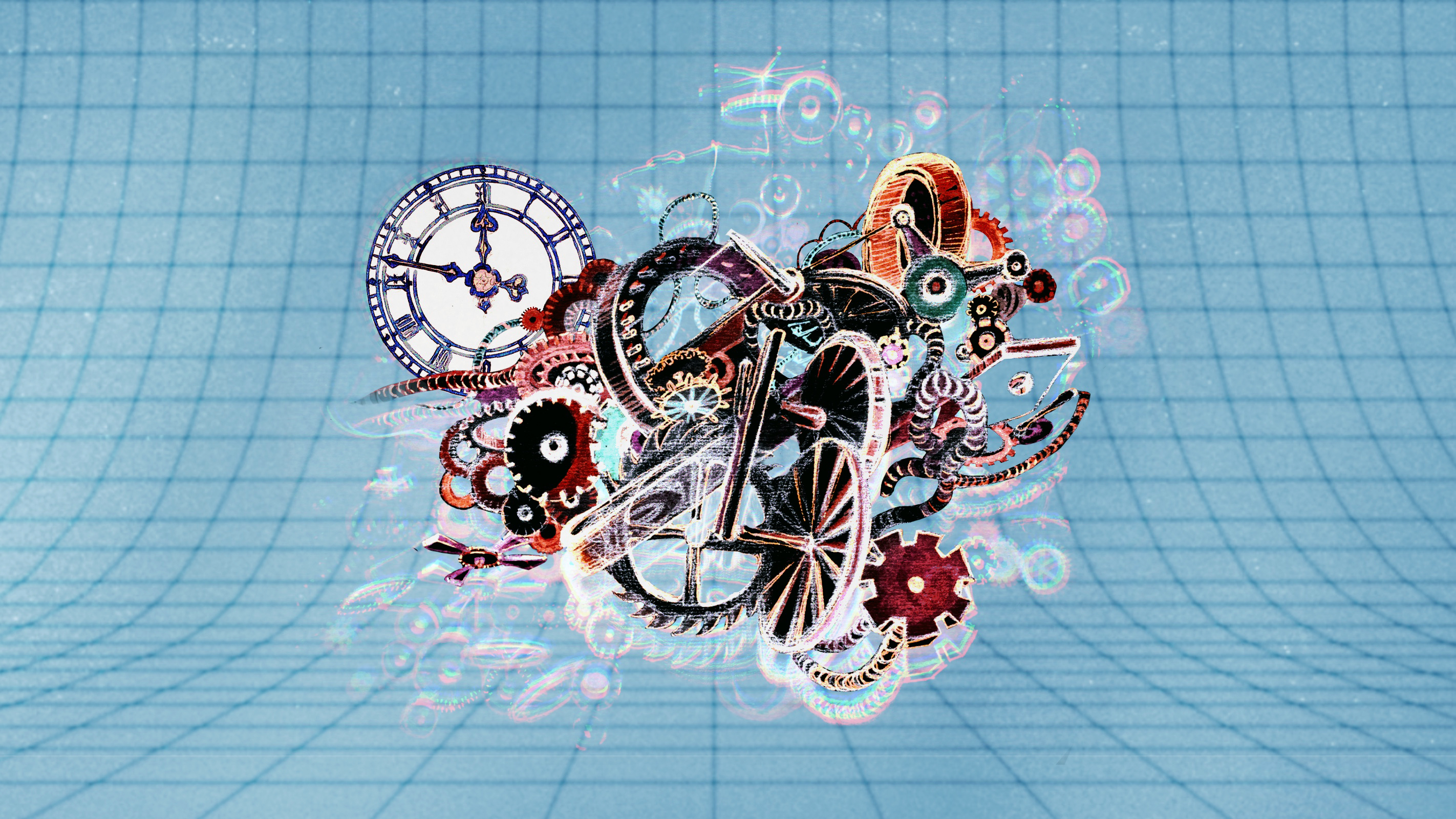

Baker’s evocation of medieval art as the ideal moment of art and religion merging together reminded me of Henry Adams’ autobiographical The Education of Henry Adams, particularly the chapter titled “The Dynamo and the Virgin.” Musing upon Chartres Cathedral and details such as the famous “Rose Window” (shown above), Adams bemoaned the loss of the energy generated by religious devotion to the Virgin Mary in the age of the dynamo and technological power. “Before this historical chasm, a mind like that of Adams felt itself helpless,” Adams writes in his (strange, at least to me) third-person way. “He turned from the Virgin to the Dynamo as though he were a Branly coherer. On one side, at the Louvre and at Chartres, as he knew by the record of work actually done and still before his eyes, was the highest energy ever known to man, the creator four-fifths of his noblest art, exercising vastly more attraction over the human mind than all the steam-engines and dynamos ever dreamed of; and yet this energy was unknown to the American mind. An American Virgin would never dare command; an American Venus would never dare exist.” The golden age was over for Adams, and the proof was right there before his eyes in stone. Baker’s compliant eerily repeats Adams’ pattern more than a century later.

At the heart of Baker’s (and Adams’) sadness is a longing for the old ways of expression. Baker compares medieval art and the paintings of Mark Rothko and can’t imagine anyone considering Rothko’s work “moving” after seeing the older “real” thing. Just as Rothko’s approach would seem impossible and incomprehensible in medieval times, much religious work seems impossible or difficult to understand today. After wars and genocides on greater and greater scales, there may be no going back to that golden age, assuming it ever truly existed. So, we are left with our own brand of devotion, our own search for new gods—in technology, perhaps, or maybe even in art. Baker seems to have lost faith in the power of art to sustain us and to sustain itself, even in obscurity. One of art’s main weapons is surprise. I’ll keep the faith that new surprises—in the form of artists working passionately outside the biennale system—await.