Failing Chemistry: When a Good Van Gogh Goes Bad

Around this time of year many high school and college students worldwide come to the sad realization that they’re failing chemistry. To them, a mole will always be just a burrowing mammal. Sometimes Avogadro’s number just has your number. Now, however, those sufferers have distinguished company—Vincent Van Gogh. A team of European scientists have isolated the chemical process that has been turning sunny yellow Van Gogh paintings into somber brown studies over the years. Their findings remind us of how artworks are truly living things, capable of living long after their creator, but also vulnerable to the ravages of time.

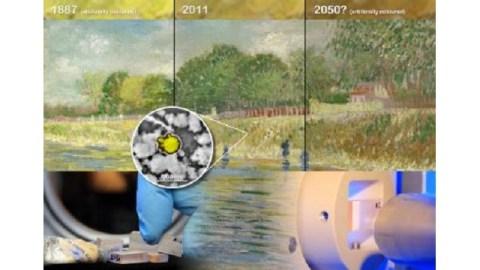

The February 15, 2011 issue of Analytical Chemistry features an article titled “Degradation Process of Lead Chromate in Paintings by Vincent van Gogh Studied by Means of Synchrotron X-ray Spectromicroscopy and Related Methods. 1. Artificially Aged Model Samples and 2. Original Paint Layer Samples,” by L. Monico et al. That scientific mouthful basically boils down to taking a small chip of a Van Gogh and analyzing it under a powerful x-ray microscope. (An animated film of the process can be found here.) With the permission and cooperation of The Van Gogh Museum, the scientific team took a microscopic sample from Van Gogh’s Bank of the River Seine. Under the microscope, they noticed that the top layer of the paint had turned a dark brown, while the paint beneath remained a bright yellow. In a chemical reaction not discovered previously, the chrome yellow paint used by Van Gogh turned dark brown thanks to a reaction to sunlight over time. Chemists understand the change as Cr(VI) to Cr(III), which basically means that the chromium in the chrome yellow had decreased, leading to a drastic color change.

The European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, where the x-ray microscopy took place; Antwerp University, home of the lead scientist; and the Van Gogh Museum developed a handy graphic (shown above) dividing Van Gogh’s Bank of the River Seine into thirds, with the leftmost third showing what the colors would have originally looked like in 1887, the center showing the colors today, and the rightmost panel showing what the work will look like in 2050, if left unprotected. The differences are striking and saddening. Even sadder is the realization that Van Gogh’s signature Sunflowers paintings feature chrome yellow heavily and have suffered this color shift, too. The brilliant colors Van Gogh intended his friend Paul Gauguin to enjoy during his time at the Yellow House they shared in Arles in 1888 no longer exist for us to see.

The failing chemistry of these Van Goghs adds another chapter to the horror novel that is the life of an art conservationist. Conservationists of Old Masters lean upon a long history of trial and error in protecting the works of those eras. Even someone like Van Gogh is a recent enough artist not to be fully understood in terms of the chemical composition of his works. Often the recipes of the paints themselves have been lost entirely or remain the proprietary secrets of the manufacturers.

The solution to this color shift seems to be some barrier that would keep harmful UV rays from striking the surface of the paintings. The damage already done may be irreversible, but at least museums can now stop it from getting worse. I can’t help but wonder if Van Gogh noticed a change in the colors of his paintings. Did Vincent watch the Sunflowers darken as an emblem of the souring of his friendship with Gauguin? Was he sensitive enough to see a kind of dying akin to the dying of real flowers in that browning? And who’s to say that the loss of the brilliant original color isn’t actually a gaining of a different, perhaps deeper meaning? In the pursuit of science, these investigators have given us the gift of a whole new way of seeing familiar pieces of art, and the artist who made them. Maybe Van Gogh’s failing chemistry is a victory for the idea of art as a continually living thing.

[Image: This illustration shows how X-Rays were used to study why van Gogh paintings lose their shine. Top: a photo of the painting Bank of the River Seine on display at the van Gogh Museum, divided in three and artificially colored to simulate a possible state in 1887 and 2050. Bottom left: microscopic samples from art masterpieces moulded in plexiglass blocks. The tube with yellow chrome paint is from the personal collection of M. Cotte. Bottom right: X-ray microscope set-up at the ESRF with a sample block ready for a scan. Center: an image made using a high-resolution, analytical electron microscope to show affected pigment grains from the van Gogh painting, and how the color at their surface has changed due to reduction of chromium. The scale bar indicates the size of these pigments. Courtesy of ESRF/Antwerp University/Van Gogh Museum.]