Essential Reading: Paul Bloom on How Pleasure Works

“The main argument here is that pleasure is deep,” Paul Bloom writes early on in his new book, How Pleasure Works: The New Science of Why We Like What We Like. “What matters most is not the world as it appears to our senses. Rather, the enjoyment we get from something derives from what we think the thing is.” Bloom argues that at the root of pleasure is our reading (or misreading) of the essence of something rather than the facts presented to our senses. This essential reading directs our appreciation of everything from our mates to our favorite music or painting. After reading How Pleasure Works, you may never look at how you look at things the same way again.

Bloom draws his essence-based pleasure theory from “one of the most interesting ideas in the cognitive sciences,” he writes, “which is that people naturally assume that things in the world—including other people—have invisible essences that make them what they are.” We take things on faith, in other words, rather than on fact. This faith-based approach comes from the ancient hardwiring of our brains. “We have evolved essentialism to help us make sense of the world, but now that we have it,” Bloom suggests, “it pushes our desires in directions that have nothing to do with survival and reproduction.” Before we could reason our way through the world, we had to believe our way through it. Despite rational revelations of these once-magical realms, we still fall for the tricks our minds once played on us.

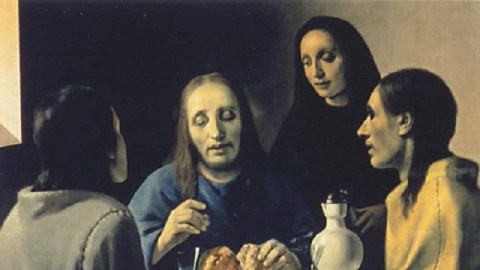

How Pleasure Works covers all the pleasure centers—food, sex, religion, and the arts. I found Bloom’s approach to the arts the most compelling. He actually begins the book with the infamous case of art forger Han Van Meegeren, who sold his The Supper at Emmaus (shown above) to Nazi leader Hermann Göring as a genuine Vermeer. Göring faced the music at the war crimes trials at Nurenberg with aplomb, but when informed of his prize painting being a fake, Göring’s smile quickly vanished (almost as quickly as the cash value of the painting itself). When we look at Van Meegeren’s clumsy fake today, it seems impossible it could ever have been considered a Vermeer. However, once the label stuck, the aura of the master blinded even experts desperate to find another work by the Master of Delft. Stories such as that of Göring’s epic disappointment lend a great power to Bloom’s argument.

“Much of the pleasure that we get from art is rooted in an appreciation of the human history underlying its creation,” Bloom believes. “This is its essence.” There’s a “life force” clinging to an original work of art that reproductions lack, the same way that something belonging to a famous person becomes an instant collectable. In art, much of that “life force” comes from the creative act itself—the displayed performance of the artist. “[C]ertain displays—including artwork—provide us with valuable and positive information about another person,” Bloom continues. “We have evolved to get pleasure from such displays… for a human artifact such as a painting, the essence is the inferred performance underlying its creation.” Something that seems hard to do will always draw our respect and inspire pleasure. When people argue about the value of a painting, it’s generally an argument over the difficulty involved. “This is why people react so negatively to modern and postmodern work,” Bloom conclude, “the skill is not apparent.” Jackson Pollock, for example, thus becomes a genius or a fraud based on whether you appreciate the skill involved in his paintings, or think that any five-year-old could do them.

How Pleasure Works deals in difficult concepts without getting bogged down in jargon. Bloom writes in a popular style but never dilutes the force of his ideas. In the end, Bloom offers a scientific argument for how we derive pleasure from works without giving some set recipe for inducing that pleasure, which would only cheapen the sources of our pleasure. We’ll always be drawn to the works of names like Picasso, but How Pleasure Works reminds us that much of the allure of any master’s oeuvre is the human element—the “life force” of the creator. If anything, knowing that we are conditioned to seek out this essence may drive us to see that essence in new masters—the Vermeer’s of today and tomorrow. Knowing how to direct that essential reading in our lives will lead us to greater pleasures tomorrow and makes Paul Bloom’s How Pleasure Works essential reading for today.

[Many thanks to W.W. Norton & Company for providing me with a review copy of Paul Bloom’s How Pleasure Works: The New Science of Why We Like What We Like.]