English Lesson 2: Homer, and Homecomings; Our American Soldiers

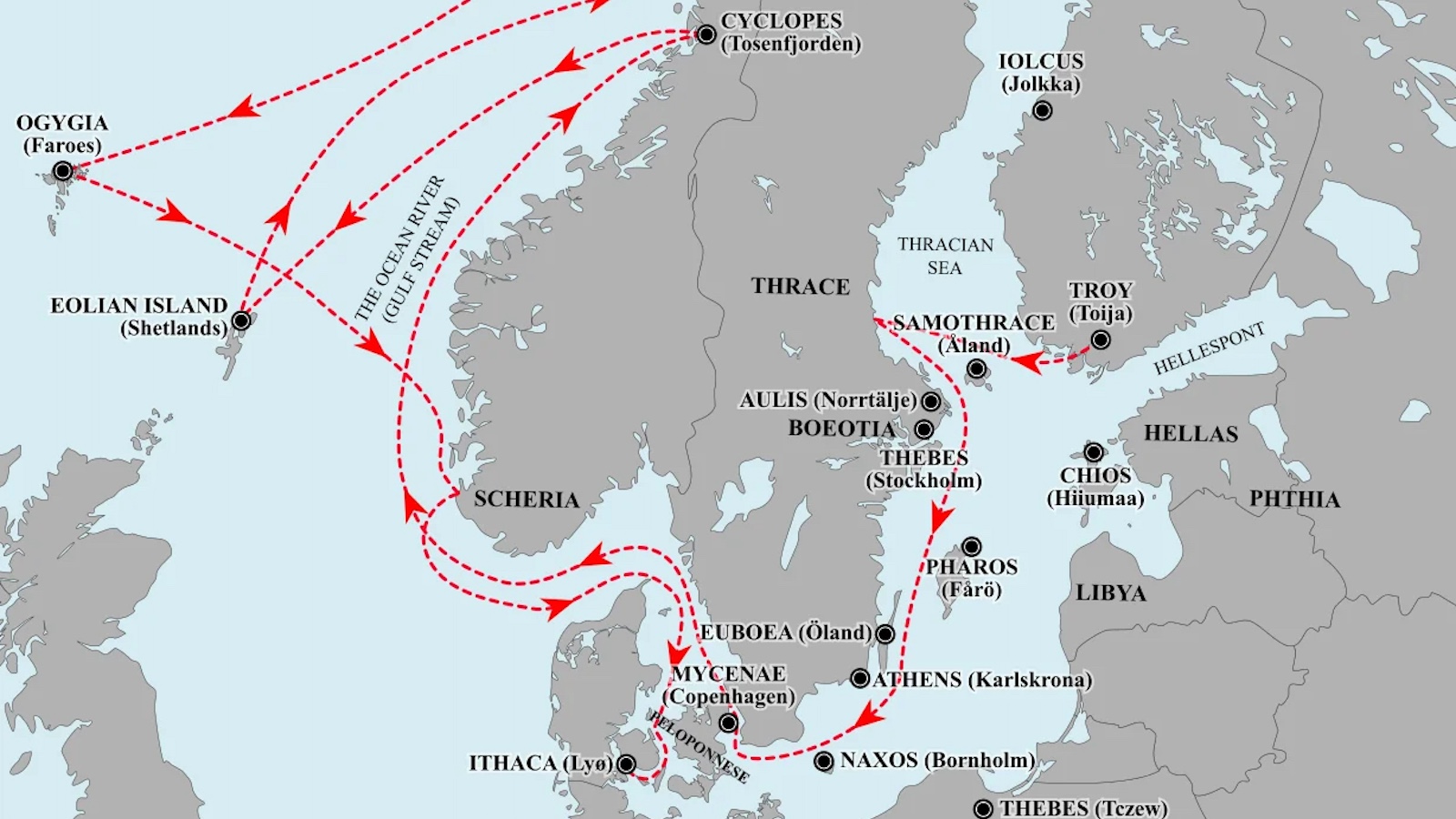

There is so much beautiful writing about war. One of the first, best stories of a soldier (and his return home) is Homer’s The Odyssey. It captures –metaphorically, and at time less metaphorically and more viscerally—the magic of being far from home, of encountering strange things that can be tough, or impossible, to translate to loved ones left far away. It also focuses on the pain of return following a long absence: the anticipations, the resolutions, the confusions. The make-up kiss. Because on this Easter so many have loved ones far away, we chose Homer today. And we chose the moment in the Odyssey when Ulysses reunites with his wife.

Romance

Penelope has waited for ten years. That’s a long time to wait for love. The fact that her husband is home now, finally, brings mixed emotions. Homer’s literary gift (one of them) was simplicity. Simplicity, and story. He had the gods to draw on for the latter. Our favorite translation was not at hand so here is the Butcher and Lang version, the one used for the original Harvard Classics edition. Here is the description of the lovers as they prepare to go to bed for the first time in a decade:

“Thus they spake one to the other. Meanwhile, Eurynome and the nurse spread the bed with soft coverlets, by the light of the torches burning. But when they had busied them and spread the good bed, the ancient nurse went back to her chamber to lie down, and Eurynome, the bower-maiden, guided them on their way to the couch, with torches in her hands, and when she had led them to the bridal-chamber she departed. And so they came gladly to the rites of their bed, as of old. But Telemachus, and the neatherd, and the swineherd stayed their feet from dancing, and made the women to cease, and themselves gat them to rest through the shadowy halls.”

The Lesson Is This

This moment is heart-breaking and powerful for what it does not say. It does not try to describe “the rites.” Nor does it try to illuminate what husband or wife was thinking, and part of what they were thinking must have been, This does not feel like home.

We know Homer is capable of rich visions, but in this—arguably the most important moment in his hero’s journey—the author exercises unique restraint. He lets us make up our own “rite” in our mind, substituting a memory from our own lives if we will. We are given enough to set a scene (the torches), no more no less.

Homer told fabulous stories. He gave the illusion of telling them simply. How did he do it? And he leaves us with a powerful idea, too, by telling the reader it was only after Ulysses had shared his own story that he was able to re-connect with his wife. The lesson is this: stories allow us to feel at home. As Joan Didion put it, “we tell ourselves stories in order to live.”

Realism

Coming home is an essential element of the journey myth—from Homer to The Hurt Locker to Sean Combs. The classical homecoming is not the marriage of a Jane Austen novel; it is not the perfect closure. The classical homecoming is more fraught with sadness and conflict and regret; this is what makes it much richer, and what keeps us returning to the myths (as much as we love marriages). Written so long ago, The Odyssey is quite visceral on reading today. Today we think of all of those who are not yet home, and of their individual odysseys.