Can We Still Read (and Believe in) Allegory?

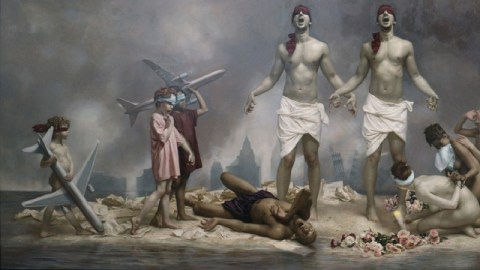

When I searched earlier this month for exhibitions related to the 10th anniversary of the September 11th attacks, I quickly realized that I had bitten off more than I could chew. A mountain of material soon grew before me, forcing me to pick and choose those that intrigued me the most and offered interesting angles to approach that unapproachable topic. One piece that slipped my grasp then but seems essentially to a discussion of artistic approaches to the tragedy and its commemoration is Graydon Parrish’s allegorical painting The Cycle of Terror and Tragedy, September 11, 2001 (detail above, click to enlarge; click link to see entire painting). Stretching 17 feet across and 6 feet tall, Parrish’s passion play refuses to be ignored. The real question, however, is whether modern viewers can read allegories on this complex, titanic scale and, if so, whether we can believe what they are saying.

Reading is fundamental, as they used to (and still should) say. It takes a sharp mind to read an allegory covering over 100 square feet, and an even sharper mind to construct it. Parrish claims that his favorite hobbies include reading the dictionary and learning Chinese. The artist skipped college and leaped at the tender age of 17 to the New York Academy of Art, an Andy Warhol-founded, graduate level art school. Precocious Parrish spent four long years painting The Cycle of Terror and Tragedy, so it only stands to reason that the painting itself requires a long, lingering, and perhaps repeated viewing.

The Cycle of Terror and Tragedy began as a commission by the family of Scott O’Brien, who died in the World Trade Center on the day of the attacks. The family wanted to make some sense of their loss, so Parrish tried to make some sense for us all with his tool of choice—allegory. The front page of Parrish’s website contains a quote from critic Craig Owens’s essay “The Allegorical Impulse”: “Allegory has the capacity to rescue from historical oblivion that which threatens to disappear.” Before the truth of 9/11 could disappear into the oblivion of time, Parrish sought to paint an allegory that would capture it in a way that would captivate the eye and mind in a way that bare historical documentation cannot.

The cyclic nature of the title comes in the panorama of age stretching across all 17 feet of the work. Children enter from the left carrying airplanes like toys. In the center, twin males stand above a fallen, third, different man. Three women kneel at the feet of the twins and physically fan out in mourning poses. To the right of the grouping of men and women, a single old man lies on the ground, where he looks to his left (our right) at a young girl, who breaks the sequence of ascending ages and returns us to the beginning of the cycle with the innocence of youth. Whether that innocence returns or not in the end depends on your view of the world.

The common thread of the figures is blindness—a series of blindfolds worn by the living only. I thought of the blindness of Oedipus, who blinded himself physically after realizing the terrible truth of his metaphorical blindness to the ugliest truths of the human condition. Parrish taps into that primal, mythic power of Sophocles and the Greek tragedians and updates it for today’s generation. On September 11, 2001, our collective eyes were opened to the potential for evil in the human soul—a realm of possibility we turned a blind eye to previously, perhaps out of an understandable need to believe in a rational, sensible world. Parrish’s allegorical figures show our blindness to us, and remove our blindfolds by donning them for us.

I’m an English teacher by trade, so reading allegory and believing in its power to teach seem natural to me. Moving aside the issue of how equipped the average American is to read this allegory, I wonder if that same average American is willing to receive the message of The Cycle of Terror and Tragedy, especially a decade after the events that triggered its creation. So many want to dismiss that day of infamy as an aberration—a single, isolated case never to be repeated. Parrish’s cyclical allegory suggests that, someday and somewhere, such a day will happen again, as it has happened before since time immemorial. Knowing that truth shouldn’t send us wailing into the darkness, but rather should make us cherish the light even more.

[Image:Graydon Parrish. The Cycle of Terror and Tragedy, September 11, 2001 (detail), 2002-2006. Oil on canvas, 77 x 210 in. New Britain Museum of American Art, Connecticut. Charles F. Smith Fund and in Memory of Scott O’Brien, Who Died in the World Trade Center, Given by his Family; 2006.116.]

[Many thanks to the New Britain Museum of American Art for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to The Cycle of Terror and Tragedy, September 11, 2001 by Graydon Parrish.]