Call to Duty: N.C. Wyeth’s Civil War Illustrations

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the American Civil War. The process of looking back at that time must also include looking back at previous attempts to look back, including (and perhaps most especially) remembrances around the 50th anniversary of the conflict’s beginning, when World War I and the question of America joining the fray in Europe plagued the national consciousness. Romance in Conflict: N.C. Wyeth’s Civil War Paintings, which runs at the Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford, PA through March 20th, focuses on the way that preeminent illustrator N.C. Wyeth envisioned the War Between the States for a new age through the prism of old-fashioned values of honor and duty.

The book publishing industry exploded with Civil War-related books as the 50th anniversary approached. Biographies of major figures, first-person accounts by aging survivors, academic reevaluations of strategies, and novelizations of real-life events hit the presses begging for pictures to match the human drama of the words. Wyeth began taking commissions for Civil War-related publications beginning in 1906. Having ancestors who fought in the French and Indian Wars, the American Revolution, and the War of 1812, as well as the Civil War, Wyeth literally grew up hearing stories of personal courage in combat, all with a personal connection. Wyeth never saw combat himself, so when his heritage impressed on him the more romantic aspects of battle, that was the feel of his artwork, sometimes even in opposition to the text it was illustrating.

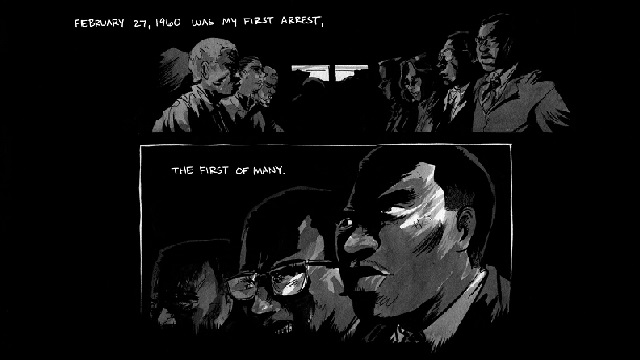

One book that meshed well ideologically with Wyeth’s art was John Luther Long’s 1914 novel War. Subtitled “What Happens When One Loves One’s Enemy,” War exemplifies the “romance” of the exhibition’s title. Long rose to fame in 1898 with the short story “Madame Butterfly,” which Giacomo Puccini turned into an opera using the libretto of an earlier play based on the story. Illustrations such as Wyeth’s cavalry charge (above) capture Long’s operatically emotional style perfectly. As emotions ran high when the War to End All Wars broke out in Europe that same year, Americans against neutrality ate up the full plate of red meat patriotism served by Long and Wyeth.

The exhibition does a fine job of recreating this atmosphere. Works by illustrators Alonzo Chappel, Harry Fenn, and Wyeth’s mentor Howard Pyle show how this romantic strain carried the day. Winslow Homer, by contrast, once looked through the gun sight of the rifle of a Union sniper he had drawn and declared it murder plain and simple—as far from romance as imaginable.

The Brandywine’s amazing collection of Wyeth’s props provides visual proof of how the artist took the real-life materials and imaginatively alchemized them into the stuff of dreams. In our present age of The War on Terror, Wyeth’s romantic take on war can seem naïve, yet the sincerity of his belief in the ideals his ancestors embodied in war cannot be questioned. The artistry of Romance in Conflict: N.C. Wyeth’s Civil War Paintings is one of faith in the value of fighting for what one believes in. Like his ancestors, N.C. Wyeth answered the call to duty in his own way.

[Image: N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945), War (1914), oil on canvas, illustration for War, by John Luther Long, published by Bobbs-Merrill Company, private collection.]

[Many thanks to the Brandywine River Museum for providing me with the image above and other materials for Romance in Conflict: N.C. Wyeth’s Civil War Paintings, which will run at the museum through March 20, 2011.]