Born Again: Beading the World Anew with Liza Lou

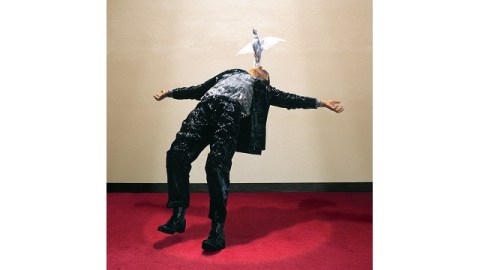

“You fall backward and you’re moved by the spirit of God and you get up and go forth and you’re a different person,” artist Liza Lou says in an interview of her “born again” Christian upbringing. “Later, as an artist, I realized I was redeeming objects with my material. There was the process of applying beads with tweezers, a very careful and attentive act—and then over time, the transformation; a kind of hallucinogenic quality, like the object was ‘saved’ or spirit-filled.” In Liza Lou, the first monograph examining the artist’s career, we see how Lou takes the craft of beading to a mind-boggling and soul-expanding extreme in works such as Man (from 2002; shown above), in which a man falls backward in epiphanal ecstasy with a dove, the classic symbol of the Holy Spirit, emerging from his mouth—all done as a fiberglass sculpture festooned with glittering glass beads. Through over 200 color photographs showing in fine detail the meticulous magic of Lou’s beads and a series of thought-provoking essays, Liza Lou will have you seeing and believing that this sometimes ugly world can be born again in beauty.

Lou actually turned her childhood into a bittersweet monologue she performed many times before committing to film in 2004 in a 55-minute, one-take, black-and-white confessional titled Born Again. (Rizzoli cleverly supplements stills from the film with pieces of the monologue printed as a mock pamphlet similar to those handed out by evangelists.) Eleanor Heartney, a writer, critic, and editor at large for Art in America, writes about Lou’s “transfigurations of the commonplace,” borrowing the title of Arthur Danto’s famous 1981 essay. Lou brings a religious fervor to her art without laying on the heaviness of doctrine. Instead, Lou recreates the reality of her religious experience in her art. Just as the film Born Again “evok[es]… both the horror and the attraction of fundamentalism… this beauty seems inextricably linked to the psychic and physical violence of renunciation and purification.” In works such as Security Fence (a razor wire-topped fence covered in glass beads) and Cell (a bead-covered prison complete with dazzling, faux feces-stained toilet), Lou takes the ugliest realities and squeezes a strange beauty from them. It’s a magical act along the lines of pulling a rabbit out of a hat, or a dove out of your mouth.

Just before Heartney’s essay spinning this hopeful religio-politico message, Peter Schjeldahl’s reprinted essay from 1998 argues against finding any message but beauty for beauty’s sake in Lou’s art. Schjeldahl, poet and art critic for The New Yorker, bemoans how “in modern times, artists ever more readily sacrificed beauty to the pursuit of other aims and oppositions, opportunities and afflictions.” But not Lou, however. Using Lou’s breakout hit Kitchen (a life-sized, bead cover kitchen portraying housewifery, complete with cherry pie popping from the oven), Schjeldahl writes, “A viewer of the Kitchen is accordingly altered to mysteries beneath its cheeky, jazzy scintillation. If you think you can make out the artist’s opinion of housewifery, in other words, you are projecting. Stop it.” Yet, despite Schjeldahl’s cease and desist order, it’s hard not to find some message in the meticulousness, an act that isn’t mutually exclusive from appreciating the sheer beauty of the art itself.

In an interview with Lawrence Weschler, Lou opens up on art and herself. “Color, color, color, color, color, hanging on those strings!… Saying ‘Touch me. Touch me!’” Lou says in justification of her choice of medium. The influences come stringing out during the conversation: George Seurat and his Pointillism, George Segal and his life-size sculpture, Claes Oldenberg for his unconventionality, Andy Warhol for his Pop Art appropriation of the commercial, and Tehching Hsieh for his disciplined suffering that helped Lou endure the agony of hand beading for years on end. Perhaps because of the ghetto of stereotypes about craft-inspired work that Lou had to fight out of, she doesn’t specify other female artists such as Judy Chicago that made craft-based art cool, or at least museum-worthy the way that the “male” arts are.

I’m sure Lou loves Chicago and her cohorts, but specifying them would be falling into the specificity that Schjeldahl cautions against and Heartney skirts without completely collapsing into. Heartney pulls back from proscribed interpretations by emphasizing Lou the believer who believes despite the reality we see every day. “Lavishing time and energy on objects like embroidered samplers, outdoor barbeques, and trailers and embellishing them with a jewellike surface, “Heartney writes, “Lou presents the radical idea that they are worthy of our attention.” Shamelessly naming the names of Jeff Koons and Damien Hirst, Heartney puts Lou on the opposite end of the spectrum from those false prophets, making Lou a savior of the quotidian with no gospel save that of accept the world as beautiful, because anything less is useless.

Liza Lou takes a difficult artist with surprising subtlety for someone working in glittering sculptures and makes her an emblem for what’s right about contemporary art and, by comparison, exactly what’s wrong. Hirst titled his diamond-encrusted skull For the Love of God, but Lou’s glass bead works are truly for the love of God—one of the next world, perhaps, but definitely of this one, too.

[Image: Liza Lou. Man, 2002. Glass beads on fiberglass. 68 x 71 x 16 inches (172.7 x 180.3 x 40.6 cm).]

[Many thanks to Rizzoli for providing me with the image above and a review copy of Liza Lou, with text by Eleanor Heartney, Lawrence Weschler, Arthur Lubow, and Peter Schjeldahl.]