Adapt to What? Laurence Smith’s World in 2050

‘Tis the season to be reading!In a sweeping panoramic new book titled The World in 2050: Four Forces Shaping Civilization’s Northern Future, UCLA professor Laurence C. Smith delivers a well-written and comprehensive account of the key drivers shaping the next four decades of evolution in our global civilization and eco-system—and the intimate relationship between the two.

Smith treats four key drivers in a constant and complex interplay: demographics, resource consumption, globalization, and climate change. But there is a fifth, he adds without hesitation: technology. Technology will shape our adaptation to the future environment, but in an incremental and practical way. Indeed, as Smith promises at the outset of the book: no silver bullets, no World War III, and no hidden genies. In other words, let’s be pragmatic about how we approach the future rather than wait or hope for Black Swans, either positive or negative.

Smith turns Jared Diamond’s famous question about why civilizations to collapse on its head, asking: what causes civilizations to grow? And where are they growing? Smith takes us to the places we would least expect to find the answer: the societies of the Arctic Circle.

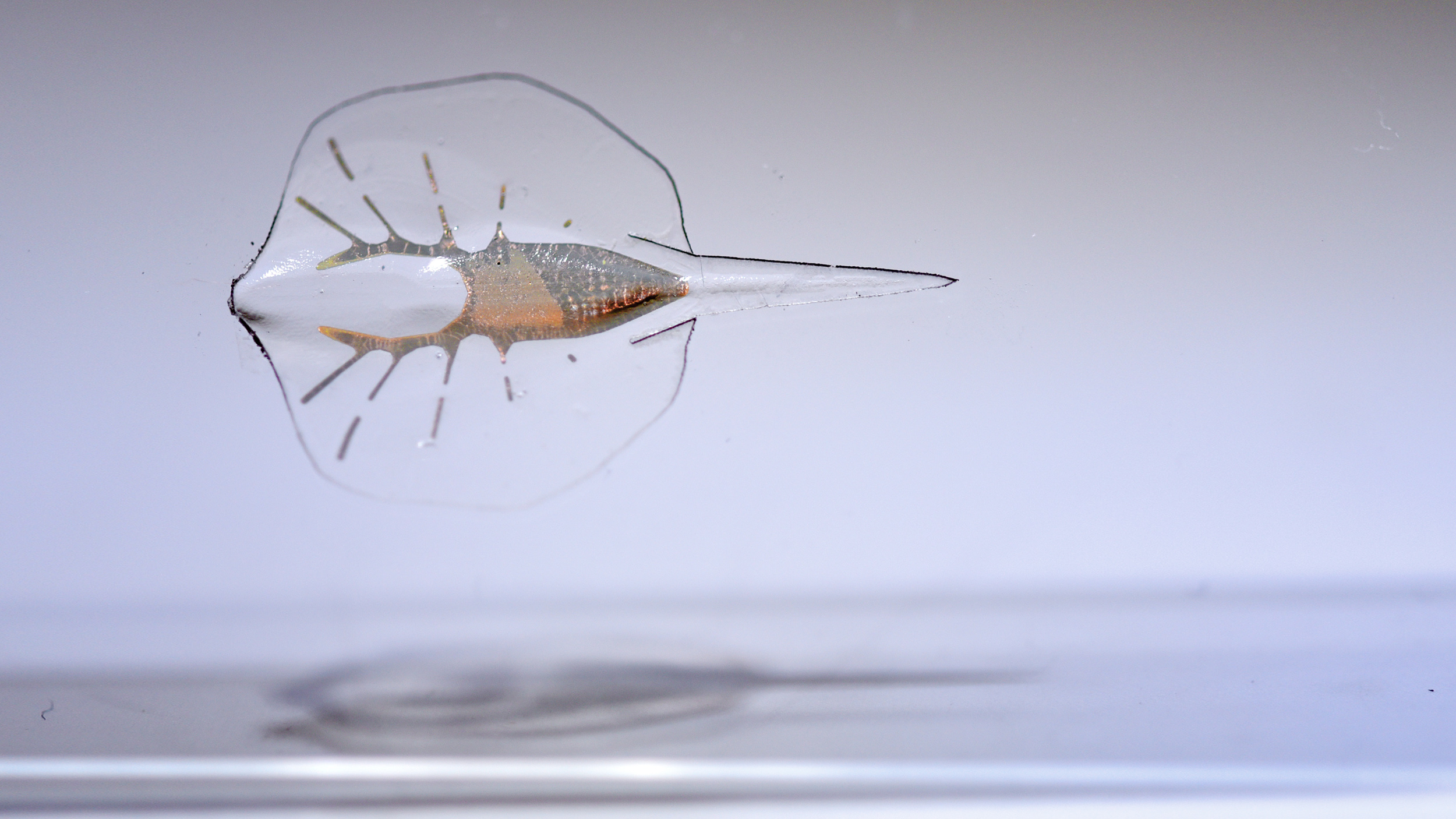

World in 2050 is a lively hybrid of academic reportage. Smith traveled on ice-breakers in the Arctic Ocean and visited indigenous communities in Finland to gather revealing stories of how the Far North is by necessity ahead of the rest of us in adapting to a warmer future. In fascinating ways—such as animal and insect life migrating to higher altitudes and latitudes—human civilization is in fact moving northward. The quite radical shifts in lifestyle we might experience by 2050 emerge through such gradual shifts we can already witness today.

Smith witnesses how even the most northern parts of Scandinavia are coming to look like Nevada, sparsely populated but dotted with confidently industrious towns specializing in niche areas like timber, natural gas production, shipping, and other areas. The gradual opening of the Northwest Passage to shipping will have an economic impact well beyond the Arctic Circle as it cuts delivery times and strengthens northern ports at the expense of those that are central nodes today.

There are other revealing stories of social and political adaptation Smith observes in his travels across the Northern Rim. He visits the newly autonomous territory of Nunavit, an Inuit populated zone the size of Mexico that has been granted self-rule by Canada and has the fastest demographic growth rate in the world’s second largest country—where previously only the population and economy straddling the U.S. border were thought to matter. Greenland too is on the verge of independence from tiny Denmark, its 60,000 population salivating over the wealth from natural gas reserves increasingly accessible as its ice-pack melts. Over in the sparsely populated Russian Far East, Chinese are increasingly swallowing Siberia (something we have discussed in a 2009 TED Talk.

Smith reveals some of the bolder hydrological solutions being discussed for the world’s water crisis stemming from climate change and consumption patterns, always honest about their potential and pitfalls. Through a complex set of aquifers, dams, and canals, a Northern Water Complex could capture the overflow of Canada’s northern rivers and pump water southward into the drying American southwest. A similar scheme in Siberia could help replenish the now trickling Amu Darya and Syr Darya Rivers of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan.

Throughout his book, Smith is balanced about he prospects for technological solutions. The fact that coal is growing in usage as a source of energy vis-à-vis oil and gas raises alarm bells given the limited success and costs associated with Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) technologies, for example. But technology does give us confidence that we will survive and can adapt. The only question we have not answered, then, is: “What kind of world do we want?”

Ayesha and Parag Khanna explore human-technology co-evolution and its implications for society, business and politics at The Hybrid Reality Institute.