A Different Kind of Hero: The Culture of Black Comix

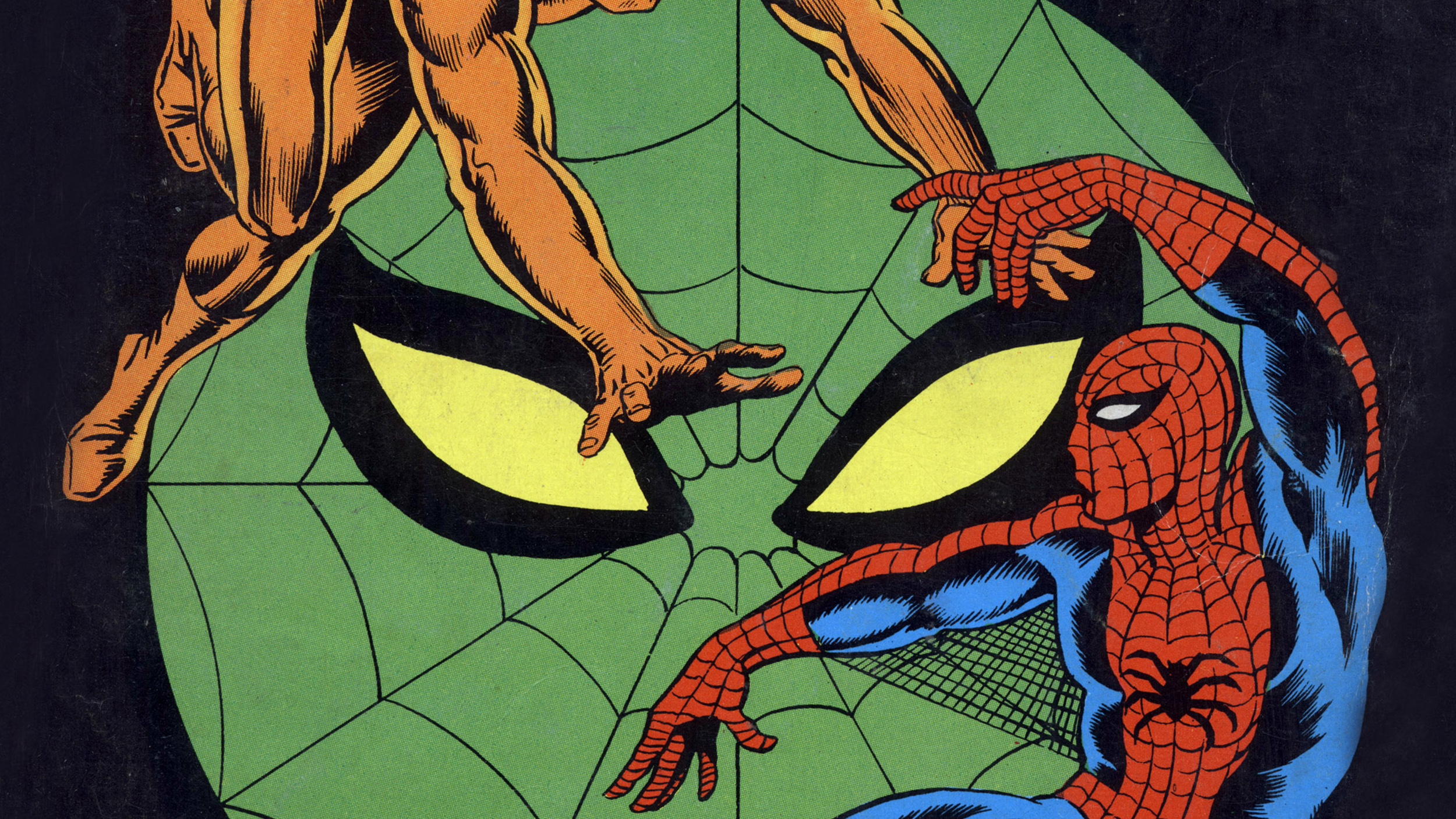

Growing up, I always found the few Black faces in superhero comic books fascinating, like rare birds. Luke Cage, aka, Power Man, bristled with attitude like Shaft on steroids. Black Lightning bolted through the air with an electrified Afro. The Falcon soared beside Captain America as a dark sidekick. Each of these heroes personified stereotypes as they tried to transcend them as heroic role models. Today, a whole new generation of cartoonists has drawn a new generation of Black heroes. Damian Duffy and John Jennings’ Black Comix: African American Independent Comics, Art and Culture collects the artistry and ambitions of these artists hoping to express the essence of their culture while finding a place in the medium itself with a different kind of hero.

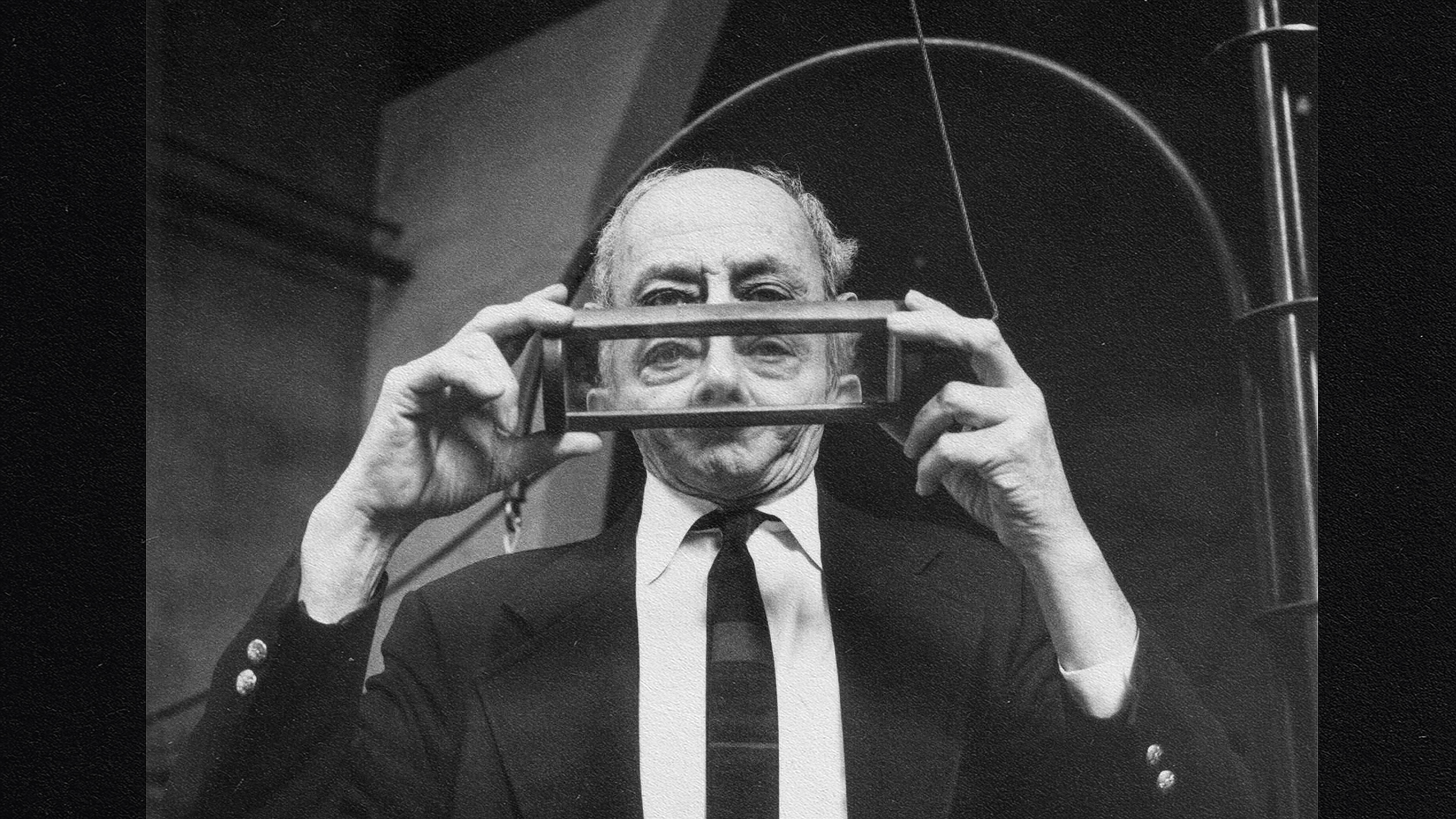

“From third grade to seventh I collected Marvel and swore by them,” admits Dawud Anyabwile, creator of Brotherman. “In seventh grade I recognized the disproportionate amount of black heroes to non-black in their books and also realized how stereotypical they were and tossed my books in the fireplace.” Brotherman and other African-American heroes take on villains in the form of racism, classism, sexism, and poverty. “African-American heroes can be a conscience of sorts for comics,” argues Stacey Robinson, creator of Abraham the Young Lion. “Our heroes don’t wear masks. Why? Simply put, our heroes represent realistic ideals. Justice, freedom and equality don’t wear masks.” The passion for social justice behind many of these heroes shines through in the art, which flies off of the page with a boundless energy and thirst for social justice not found in even the biggest mainstream heroes of the big comic companies. Duffy and Jennings examine the thinking behind these heroes and profile deeper thinkers such as William H. Foster, III, and the African-American academics known collectively as “Critical Front.” When the “Critical Front” academics take on personae such as Anthroman and Mad Law Professor, you get a sense of how this is serious play (or fun philosophy) in action.

Duffy and Jennings present the artists in alphabetical order, which seems the most democratic thing to do. All of these artists stand together as a multifaceted, diverse snapshot of the intersection of such forces as hip hop and manga in the artwork and writing of African-American independent comics. For the most part, the images are allowed to speak for themselves, but extra attention is given to standout figures, such as Anyabwile of Brotherman fame and Richard Tyler, II (aka, Uraeus), creator of Jaycen Wise, an immortal traveler “charged with the lofty responsibility of battling the forces of ignorance and darkness, to ensure the eternal preservation of knowledge, truth and light.” You’ll find yourself flipping back and forth throughout the book, lingering over different images every time. For someone unfamiliar with the realm of African-American independent comics, Black Comics opens up a whole new world of heroic possibility.

“The good news is we are here, and we are growing,” artist Turtel Onli, “the father of the Black Age of Comics,” announces. With their own conventions and even a museum of Black superheroes, Black comics are, indeed, present and increasingly accounted for by the Black audience they primarily serve. The next step, which Black Comix should help happen, will be to rise even further into the consciousness of mainstream America. Only then will Brotherman, Jaycen Wise, and others battle the injustice they were created to fight against at its source.

[Many thanks to Mark Batty Publisher for providing me with a review copy of Damian Duffy and John Jennings’ Black Comix: African American Independent Comics, Art and Culture.]