Consider the Slime Mold: How Amoebas Form Social Networks

What’s the Big Idea?

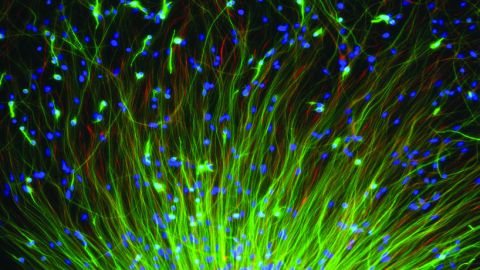

“It turns out we’re not the only species that assembles ourselves into networks,” says physician and sociologist Nicholas Christakis in his Floating University lecture, “If You’re So Free, Why Do You Follow Others?” Consider the slime mold, for instance. When placed in a maze with food at the end of it, individual amoebas will connect to create a sort of “super organism” capable of performing feats that no single organism could do on its own.

One mycologist, Toshi Nagagaki, found that the path taken through the maze by this “super organism” was more efficient than the path proposed by his graduate students.

“If you put oat flakes at the entrance or the exit of the maze this simple organism will change its shape and connect to the two sources of food by finding the minimum path length solution between the two points,” says Christakis. “Obviously if you ask, ‘Can this amoeboid fungus solve a maze?’ the answer is no, but the maze-solving ability emerges as a result of interactions.”

What’s the Significance?

Christakis describes an experiment conducted by his colleague, Mark Fricker, in which amoeboid fungus was placed on a map of England, with “little oat flakes at every city.” The fungus was able to create an optimal path through the country, that “actually imitated – and [was] in many ways better” that the human-designed railway network. But what, besides good design, is the point of a connected life?

For much of the 20th century, social scientists assumed that competition and strife were the natural order of things, as ingrained as the need for food and shelter. The world would be a better place if we could all just be a little more like John Wayne, the thinking went.

Now researchers are beginning to see teamwork as a biological imperative, present in even the most basic life forms on Earth. And it’s not just about fairness, or the strong lifting up the weak. Collective problem-solving is simply more efficient than rugged individualism.

In Christakis’ words:

Social networks are a resource that we can all use. They are a kind of social capital. When they think about capital, most people think about money, but really capital is any stock of resources that can be put to productive use. In order to create capital you have to invest skill and effort. You have to know something and do something – and you have to work upon the world and transmute it. You have the change the world.

To subscribe to the Floating University course “Great Big Ideas,” click here.