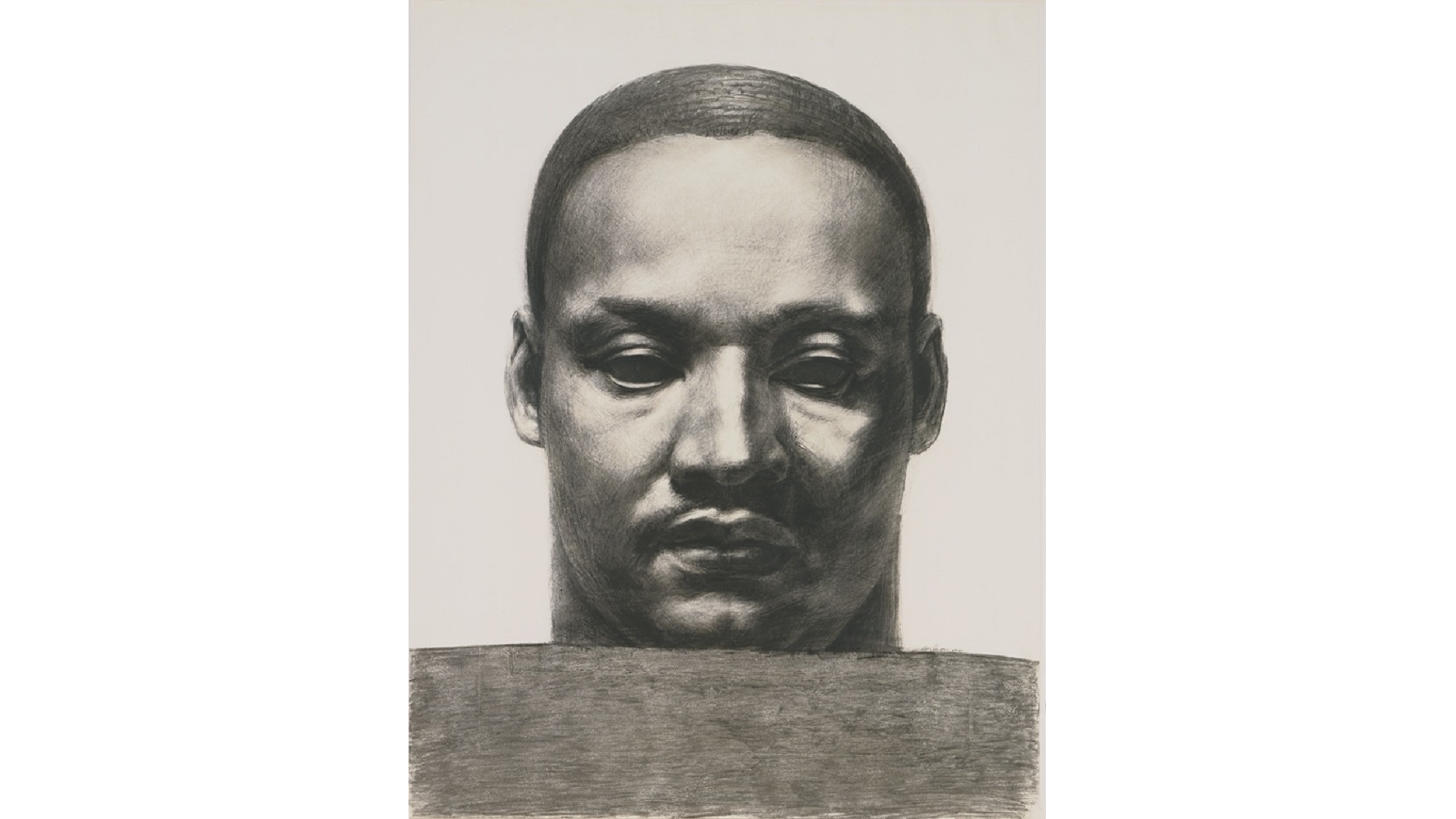

Why Richard Pryor Still Speaks to Artists

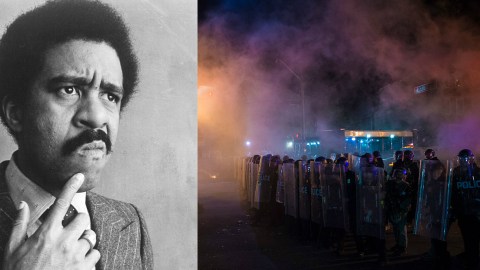

Few comedians could find as much truth and humor in the African-American experience as Richard Pryor. Dropping N-bombs and obscenities with abandon, Pryor never gave up hope that laughter could be found in the saddest of racial realities. Even before his death in 2005, Pryor’s distinctive voice — full of intimacy and rage — has been imitated widely, but never duplicated. Now artist Glenn Ligon looks to Pryor once again, not to listen to his words once more, but to “listen” to how Pryor’s body — standing in for the feared, repressed, and persecuted black body in American society — “spoke” then and still speaks today.

Image: Cover of Richard Pryor’s 1976 album Bicentennial N***er

Richard Pryor mainstreamed the use of the N-word with his comedy, going so far as to incorporate it into the title of his Grammy-award-winning 1976 comedy album Bicentennial N***er (shown above). Pryor’s possession of the slur transformed the word into something that could become a source of power for its targets. In that sense, Pryor’s the godfather of much of the rap and hip-hop sensibility. Pryor’s brand of “furious cool” (as David and Joe Henry called it in their insightful 2013 study Furious Cool: Richard Pryor and the World That Made Him) inspired white and black audiences to laugh, but for drastically different reasons. By revealing the most painful, intimate depths of the African-American experience, Pryor made African-Americans look inward while opening the eyes of whites.

Artist Ligon began using Pryor’s jokes as the basis for paintings in the early 1990s and continued through the mid-2000s. For example, in 2004’s When Black Wasn’t Beautiful #1, Ligon reproduced the following Pryor bit on canvas:

“I remember when black wasn’t beautiful. Black men come through the neighborhood saying, ‘Black is beautiful! Africa is your home! Be proud to be black!’ My parents go, ‘That n***er crazy.’”

But while Pryor’s performance of the joke is before a crowd laughing together, Ligon’s reproduction forces an individual response. Also, Ligon’s stencil technique makes it physically difficult to read the words at times, just as it should be emotionally and spiritually difficult to recognize the truth of Pryor’s words. Ligon forces you to be conscious of the words themselves and what they mean. At the same time, as you stand there reading, you feel others in the gallery watching you reading, leading to a self-consciousness of yourself sharing in the uncomfortableness of the joke.

Image: Glenn Ligon. Live, 2014. Seven channel video. Duration: 80 minutes. Installation view Glenn Ligon: We Need to Wake Up Cause That’s What Time It Is, Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY (January 16–April 17, 2016). Photography: Farzad Owrang. © Glenn Ligon; Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine, New York.

Whereas Ligon previously focused on Pryor’s words and language, Glenn Ligon: We Need to Wake Up Cause That’s What Time It Is focuses on Pryor’s unspoken message — his body language. In this new exhibition, Ligon takes the concert footage of Pryor’s Live on the Sunset Strip and splits it apart, virtually tearing Pryor’s body apart (examples shown above and below). One screen shows the original version of Pryor, while six others simultaneously focus on fragments of the comedian: hands, head, mouth, groin, and even shadow. By silencing the footage, the viewer is forced to pay attention to Pryor’s physical delivery of the comedy. By showing each body part on its designated screen only when it appears in the full original, Ligon points out how impermanent the body is.

Before you enter the video installation, however, Ligon asks you to read his Pryor joke painting, Therapy #2. The 2004 canvas reproduces the following Pryor bit:

“Black people are frightened to death of therapists. For some reason, of all the people on the planet in America we some motherf***ers that need some therapy. You believe me, ‘cause we f***ed up. We f***ed up ‘cause we got to be insane ‘cause we ain’t killed you mother f***ers.”

In the age of #BlackLivesMatter, Ligon’s exhibition offers a kind of “physical therapy.” As the bodies of black men such as Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, and so many more pile up, this exhibition reminds us of how the black male body’s become a focal point for American society — the place where all the unspoken anxieties come to a head, usually resulting in violence.

Pryor produced Live on the Sunset Strip after his almost fatal freebasing incident, in which he suffered burns over half of his body. “When you’re running down the street on fire,” Pryor jokes, “people will get out of your way!” The fire-engine red suit Pryor wears in the concert film may allude to this trial by fire. Listening to that concert, you can’t help but wonder at Pryor’s physical presence on stage after such a painful recovery. By turning off the sound, however, as Ligon does, you not only see the pain expressed by Pryor’s body, but also get a sense of how the male black body embodies the unresolved, untreated wounds of American society. #BlackLivesMatter, but #BlackBodiesMatter more. Ligon gets under Pryor’s skin to get under your skin in a remarkably suggestive way.

As the press release points out, during the original performance, Pryor explains how “the madder I get, the quieter I get,” followed by a silent pantomime of fast, furious, and foul gestures and language. Even Pryor himself knew the deeper meaning and message of inhabiting a black body in American society, with all the tropes of masculinity and race weighing it down. Glenn Ligon: We Need to Wake Up Cause That’s What Time It Is sounds an alarm in a subtle, yet provocative way to all Americans who wish the dream of a post-racial country could come true. Nearly a decade after his death, Pryor still has something to say, even when he’s saying nothing at all. Ligon makes it possible for us to hear him just a little clearer.

[Image at top of post: Richard Pryor performing in the 1982 film Richard Pryor: Live at the Sunset Strip.]