How China’s Monkey King changed Western literature

- Despite being a side character, the all-powerful Monkey King steals the show in Wu Cheng’en’s allegorical novel Journey to the West.

- Over the years, traces of the Monkey King’s influence can be found everywhere from Superman comics to Japanese manga and anime.

- The character’s impulsive nature, optimistic attitude, and strong sense of self-worth make him an interesting character for writers to play with.

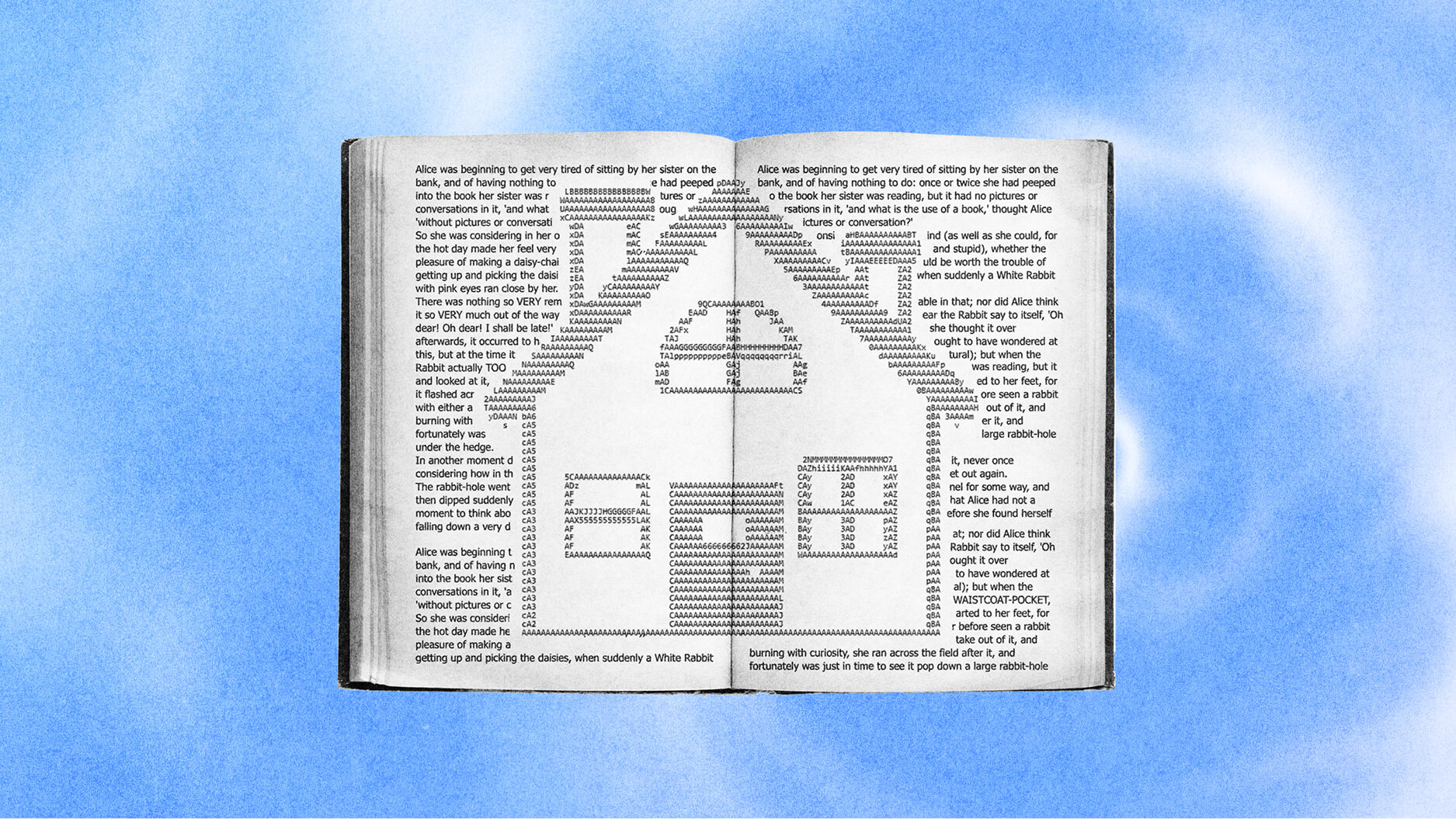

Even if you have never read — or let alone heard of — the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West, you have probably been exposed to its contents in one way, shape, or form. Written in the late 16th century by a Jiangsu-born artisan who dreamed of becoming a poet, it tells the story of a Buddhist monk who must carry an irreplaceable religious text from India to China without getting eaten by the demons that await him along the way.

Today, Journey to the West is widely and rightly considered one of the greatest novels ever written. Along with Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Dream of the Red Chamber, and Water Margin, it is ranked as one of four “Classic Chinese Novels,” or texts that scholars say have left a deep imprint on East Asian thought and mythology. Thousands of critics have mined it for hidden wisdoms, and nearly every year the story reappears in a television adaptation or film, such as the 2016 Chinese movie The Monkey King 2.

There are many viable explanations for the enduring popularity of Journey to the West. Talking with the BBC, a Chinese studies scholar named Jason Zhuang said the storytelling abilities of the text’s author, Wu Cheng’en, were simply unmatched. Despite its age, the novel could outpace your average Hollywood blockbuster, and its comedic timing is better, too. Strip away the fighting, and you are left with a compelling tale of emotions and relationships.

Like any literary masterpiece, Journey to the West also imparts inspiring and helpful life advice. Each of the principal characters represents a different piece of the human puzzle: mind, body and spirit, to put it broadly. By turning his own protagonists into semantic building blocks, Cheng’en constructs philosophical arguments out of each adventure, showing how certain Buddhist and Taoist practices can (or cannot) help people overcome problems.

From stone monkey to heavenly warrior

For better or worse, much of the book’s impressive legacy seems to hinge on just a single character, one whose imprudent, humorous and above all awe-inspiring nature seems to have struck a chord with audiences across the world, regardless of era or nationality. Cheng’en may well have anticipated such a positive response; if not, he would not have reserved the book’s opening chapters to tell this side character’s entire history.

Sun Wukong, better known to western readers as the Monkey King, or simply Monkey, started life as an ordinary simian until an existential crisis led him to become a disciple of an immortal Taoist sage. After gaining immortality himself and unlocking several other superpowers along the way — including the ability to fly on a cloud and transform into 72 different animals and objects — Monkey ended up on a watchlist of deities who considered him a threat.

Sooner or later, Monkey and the entire Japanese pantheon did indeed clash, and Monkey — whose unparalleled powers had, by this point, caused him to develop his own god complex — stood up and came out on top. It was not until the pantheon’s leader, the Jade Emperor, called on the help of Buddha that the war came to an end. Using Monkey’s lack of enlightenment against him, Buddha trapped the usurper under a magically sealed mountain.

Monkey remained under this mountain for more than 500 years, until a monk named Xuanzang — the novel’s true protagonist — crossed paths with the prisoner on his way to India. The two decided to make a deal: Xuanzang would break Buddha’s seal if Monkey agreed to be his bodyguard during the perilous journey ahead. Monkey obliged. After withstanding all of the book’s tribulations, he finally reached enlightenment on his reunion with Buddha.

Because the book was written in a style that relied heavily on action and description, Journey to the West does not lend itself easily to quotations. As such, the best way to get to know Monkey would be to either read the book or the opinions of those who have, suggested the Chinese author and translator Lin Yutang of the famed character: “Monkey was clever, but also conceited; he had enough magic to push his way into Heaven, but not the sanity and balance and temperance of spirit to live peacefully there.”

Cross-cultural representations of the Monkey King

Put like this, it almost seems as if Journey to the West is more about the Monkey King than his mentor, Xuanzang. But this is not the case. Scholars have stressed time and again there is more to the story than its flashiest character. Still, Sun Wukong has taken on a life of its own, resonating with both Eastern and Western nations on an even greater scale than the novel of which he is part.

In Japan, Monkey has served as the inspiration for countless of manga and anime protagonists, including Dragon Ball’s Son Goku, One Piece’s Monkey D. Luffy and even the character of Lupin III, at least insofar as he appeared in Hayao Miyazaki’s adaptation of him. Traces of the character and the folktales surrounding him can be found in American media, from the earliest Superman comics to the more recent animated series The Last Airbender.

Why Monkey is so beloved is still debated to this day. His impulsive behavior, optimistic attitude, and strong sense of self-worth make the character easy to mine for storytellers trained in Western traditions. But the character also speaks to Eastern audiences in ways that are unique to them. Zhang Jinlai, a Chinese actor who played Monkey in a popular 1980s TV show, said that to truly understand him you have to first understand China.

While American depictions of Monkey focus on the character’s physical prowess, Chinese adaptations are more concerned with his personality and spirituality. “In Chinese culture,” writes Qing Yang, a literary scholar at Sichuan University who compared cross-cultural representations of the character, Monkey represents “resistance, longing for freedom and individualistic heroism.” At the same time, he can also be interpreted as a symbol for the poor and downtrodden.