‘Bridge of Spies’: The Coen Brothers’ Unintentionally Radical Script

Bridge of Spies opens everywhere October 16, directed by Steven Spielberg, starring Tom Hanks and Mark Rylance, written by Matt Charman and Joel and Ethan Coen.

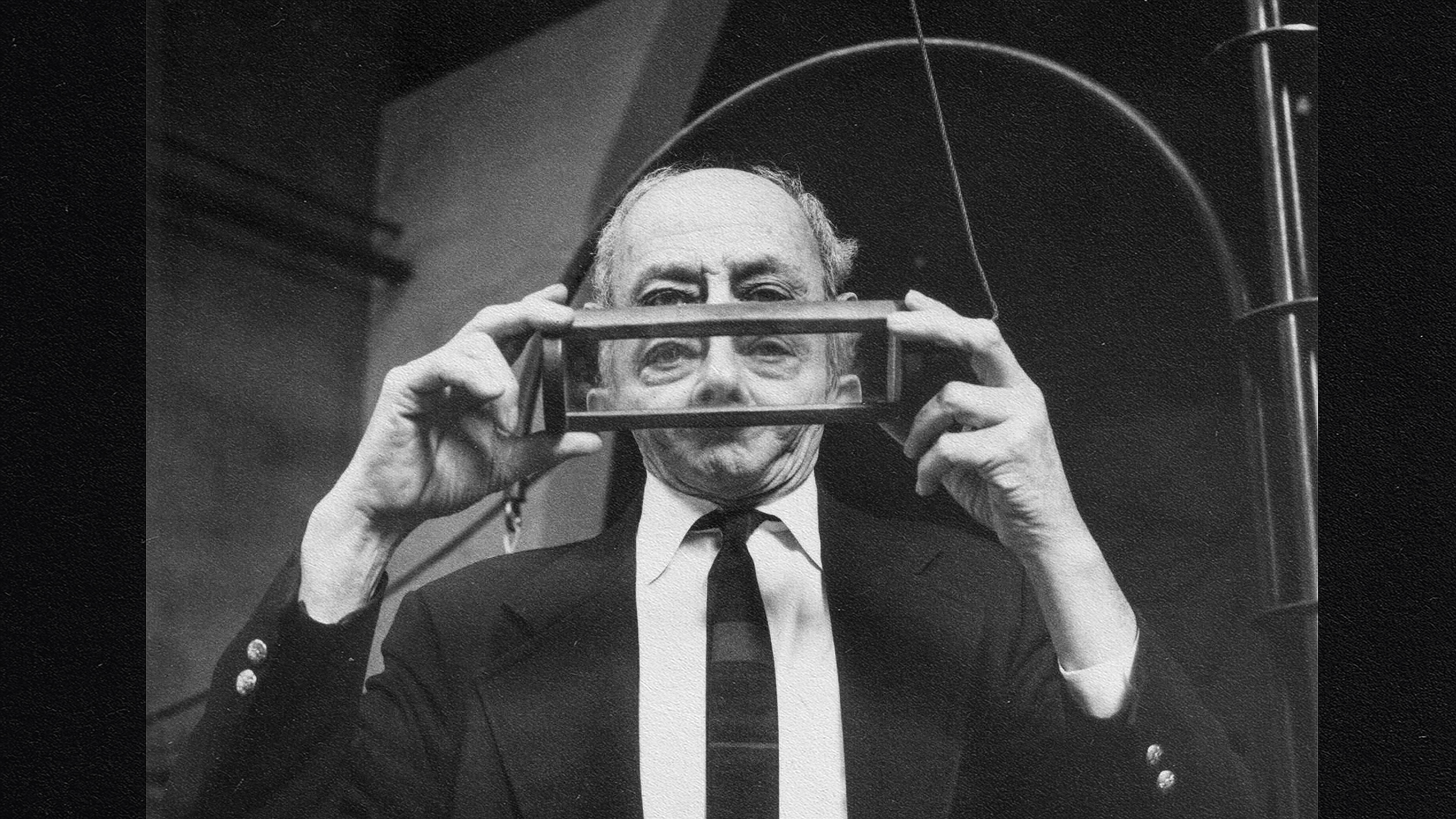

Set during the 1950s Cold War, Bridge of Spies turns on an unlikely camaraderie between patriotic American James Donovan (Tom Hanks) and Soviet spy Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance). Donovan’s character is an insurance claims attorney who, summoned by patriotic duty, vigorously defends the spy before a justice system ready to skip due process and apply capital punishment. In one of his many triumphs, Donovan gets the spy sentenced to prison instead of being killed by the state.

Donovan’s desire to spare the spy’s life is more pragmatism than principle. He foresees a day when an American spy is captured by the Soviets and sees Abel as a bargaining chip. Indeed an American spy is captured by the Soviets — a U2 spy plane pilot — and Donovan must negotiate behind enemy lines to bring our boy home.

Bridge of Spies isn’t quite a spy-thriller worthy of John le Carré (A Most Wanted Man, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy). The casting is too blunt and moments are played for chuckles rather than intrigue. But neither is there an easily digestible message one can leave the theatre with.

There is nothing pragmatic about Donovan’s pursuit of justice, however. It is dangerously pure. Even when his wife and children are shot at in the family home for his defending public enemy #1, he is not for a moment deterred.

What is striking about the film is how non-ideological it appears at a time when two ideologies — communism and capitalism — competed fiercely for control of the world. In this sense, the film is refreshing. If any American decade is an easy target for criticism, it is the 1950s. Plenty of films have been about the time’s social ills and rightfully so.

The most nefarious force in the film is the Institution. Both American and Soviet governments are transparently corrupt, unashamedly immoral, and staffed by buffoons. Only the individual’s moral sense can rise above the noise. There is nothing pragmatic about Donovan’s pursuit of justice, however. It is dangerously pure. Even when his wife and children are shot at in the family home for his defending public enemy #1, he is not for a moment deterred.

This absolutist defense of traditional morals, i.e., honor before self-interest, is not an advert for American exceptionalism. Who could possibly stomach such propaganda after Guantanamo, after Iraq, after #blacklivesmatter, after our complacency with school shootings, after the scandals that caused the financial collapse, and considering the current state of national governance? Today, to speak about America with any attempt at honesty is to speak critically, skeptically, and cynically.

What is most remarkable about Bridge of Spies is its return to a pure morality that is radically out of touch with our current level of cynicism (this review, for example). In his book Trouble in Paradise, Slavoj Zizek quotes G.K. Chesterton on the topic of crime stories:

“…civilization itself is the most sensational of departures and the most romantic of rebellions … When the detective in a police romance stands alone, and somewhat fatuously fearless amid the knives and fists of a thieves’ kitchen, it does certainly serve to make us remember that it is the agent of social justice who is the original and poetic figure, while the burglars and footpads are merely old cosmic conservatives, happy in the immemorial respectability of apes and wolves. The romance of the police … is based on the fact that morality is the most dark and daring of consequences.”

—