5 of the richest companies in history

Wikimedia Commons

- You’ve definitely heard of Apple. But what about the Dutch East India Company?

- Did a 1911 Supreme Court decision result in more millionaires in America than any other court case?

- One example of how not to do it: the rise and fall of the Mississippi Company.

The VOC flag. Photo credit: Michael Coghlan via Flickr.

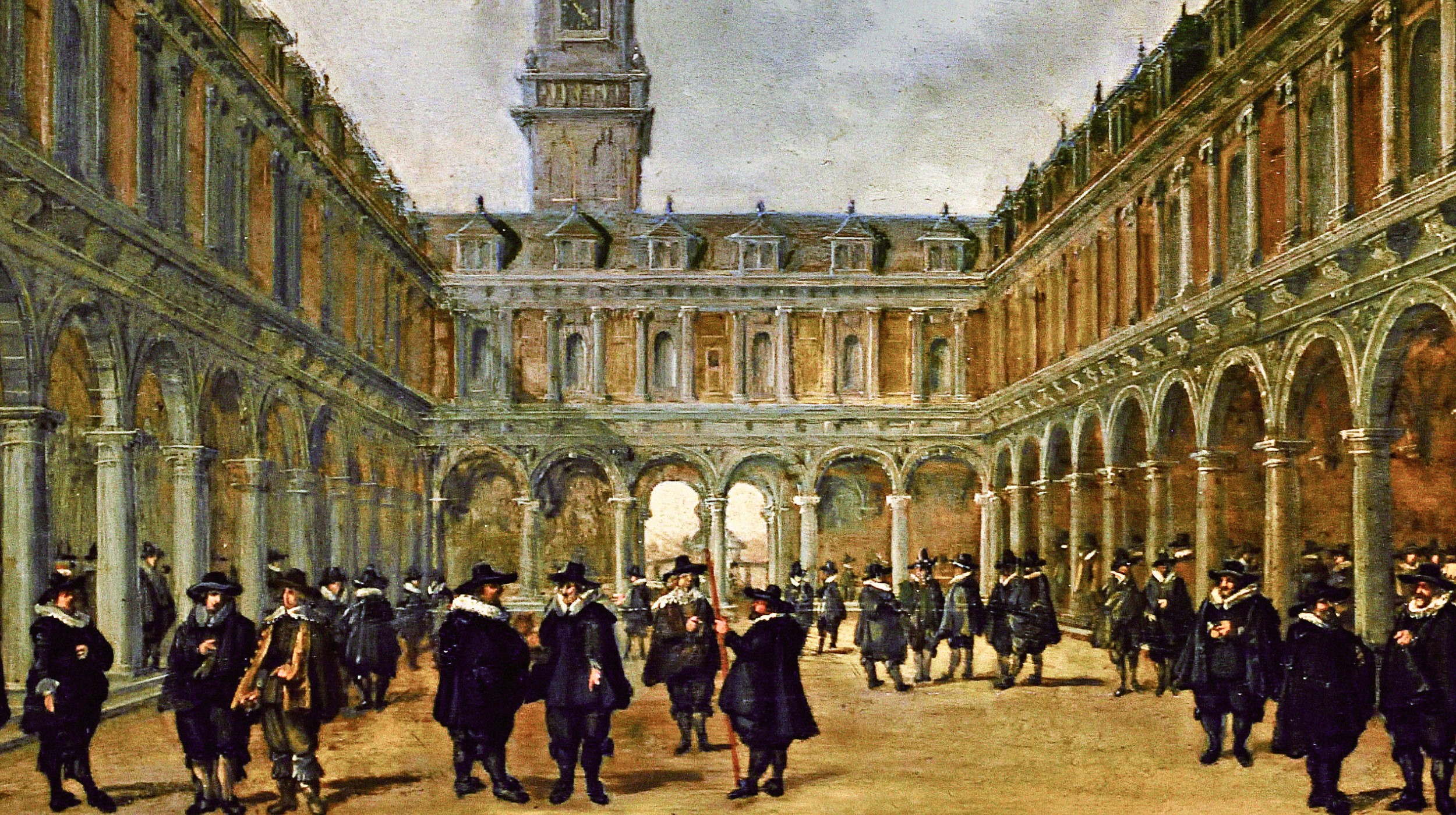

Dutch East India Company

Known under the initials VOC (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie), the Dutch East India Company would be worth about $7.8 trillion today. Founded in 1602, it accomplished globalist capitalism some 400 years before everyone else did. It began as a shipping company — with a 21 year monopoly on the Dutch spice market — before branching into almost every aspect of the spice trade, from production to consumer sales, while still keeping a massive footprint in the shipping industry at large for more than 100 years. But this success came at a massive moral cost: they exploited foreign workers, imprisoned many, and benefitted hugely from the slave trade. But for that 100 years, VOC was a gargantuan presence around the world. They controlled armadas of ships that were able to fight off navies and take territories, an impressive feat for a privately held company (imagine if Arby’s began to take over entire city blocks).

You could probably say that the very idea of globalism stems from the VOC. Europeans wanted spices and textiles from Asia, but Asia didn’t want very much in return except for precious metals — which Portugal and Spain had in abundance at the time. Paraphrasing here for the sake of brevity, the VOC created a hugely profitable trade corridor between Asia and Europe. And from around 1620 to 1630, the VOC used profits to reinvest in itself, becoming exponentially bigger in the process.

John Law

The Mississippi Company and the South Sea Company

Ooh, boy. This is a story. In you lived in France in the early 1700s you’d have likely heard of the Mississippi Company. Depending on which version of their history you read, you’ll get two very different narratives about the company. They either controlled much of France’s commercial interests in the New World for 20 years before fizzling out due to mismanagement… or they shipped convicts and prostitutes to Arkansas and Louisiana to ostensibly work for them in order to inflate their numbers and increase speculation on paper which nearly led to bankrupting France.

Both versions of the company history hold true. The central figure of the story was a Scottish economist named John Law who convinced the then-king of France, Louis XIV, to allow him to run the Banque Générale Privée (“General Private Bank”) in 1716, taking on the national debt, which he then used to finance the Mississippi Company to organize trade with the New World. Law’s company, in the space of two short years, bought several other shipping companies in order to create a near-monopoly of trade on the world’s oceans. In order to fund such a massive operation, in 1720 the Mississippi Company became tied into the Banque Générale, which became the Banque Royale. Law kept pushing the valuation of his company and soon began shipping prisoners and prostitutes to America to work for his company as part of a marketing scheme which promised huge returns on stock.

The thing is: the scheme worked… but only for a very short while. Stocks soared, and then crashed. The whole cycle lasted just 4 years. Law fled to London and then to Venice, where he gambled away what he had left and died penniless in 1729 in Venice.

At roughly the same time, a joint-stock company was formed in England called the South Sea Company. John Law had been exiled from England after killing a man in a duel in 1694 (and was only free as he’d managed to escape prison and flee to Amsterdam), but after word of his successes with the Mississippi Company reached British shores they decided to set up their own similar joint-stock venture. The South Sea Company was given a monopoly to trade with South America. It, too, overvalued itself… mostly through speculation of a £70 million line of credit through the King of England himself, which never actually happened. A rush on stock by a who’s-who of the who-was in England at the time (including Sir Isaac Newton, who had bought about £22,000 in South Sea stock) — followed by a slew of insider trading by South Sea employees who realized the bubble was about to burst — brought about a huge economic crash.

Both the South Sea Company and the Mississippi Company didn’t actually do much trading with the Americas. It was mostly just a clever marketing ploy combined with public gullibility.

Businessmen in Saudi Arabia

Invited foreign and Saudi investors attend the Future Investment Initiative (FII) conference in Riyadh, on October 24, 2017.

The head of oil giant Saudi Aramco said that a lack of recent investments in the oil sector could lead to a shortage of supplies. / AFP PHOTO / FAYEZ NURELDINE

Saudi Aramco

Still around today, Saudi Aramco is one of the world’s biggest oil producers. Adjusted for inflation, at it’s height, the company was worth $4.1 trillion.

When oil was discovered in Bahrain in 1932, the Saudi government accepted a bid from the newly-founded California-Arabian Standard Oil Company to search for oil in nearby Saudi Arabia. Soon after, Texas OilCo bought a 50 percent stake in California-Arabian. For the next five years, no oil was discovered and the company was hemorrhaging money. Finally, oil was discovered in Dhahran in 1938 and production quickly soared. Changing its name to Arabian American Oil Co (or, for short, Aramco) in 1944, it was then forced to share its profits with the Saudi government starting in 1950. This essentially nationalized the oil production, leading the huge amounts of money for the Saudi government. In 1980, the Saudi government assumed full control of Aramco.

While not quite as colorful a history as the Mississippi Company, Aramco is itself responsible for what economists now call the “golden gimmick” — wherein (and I’m definitely paraphrasing) a country’s government takes shares from the company because it’s just so darn profitable. Must be nice.

John D Rockefeller circa 1930: at work in his study. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Standard Oil

Ever heard the phrase “richer than a Rockefeller”? Well, that’s because John D. Rockefeller founded Standard Oil in 1870 in Ohio. It became the largest oil refinery in the world for a number of years. Adjusted for inflation, in 1905, it was worth well over $1 trillion in today’s money.

Rockefeller controlled 90 percent of the oil in America during the early 20th century; oil was used during that time primarily as a light source for lamps (this is before electricity became widely available) and then, with the invention of the car, became fuel for automobiles. Rockefeller was the cornerstone of two major industries until 1911, when Standard Oil was dissolved by none other than the U.S. Supreme Court for being an “illegal monopoly.” When Standard Oil was broken up into 34 different companies — the shares of those companies became worth more than Standard Oil was, thus making Rockefeller obscenely wealthy instead of just extraordinarily wealthy.

How rich was John D. Rockefeller? Well, in 1913 he alone was worth about 2 percent of the entire U.S. GDP — about $400 billion, when adjusted for today’s inflation. He attributed his success to a hard work ethic, his faith in God, and his abstinence from alcohol.

Oh, and those 34 companies? Two of them, Jersey Standard and Socony, became Exxon and Mobil, respectively. They eventually merged into a new company called Exxon-Mobil. That single company took over exactly where Standard Oil had left off and became a huge player in the gasoline industry. In 2007, it was worth $572 billion.

Apple CEO Steve Jobs speaks during an Apple special event April 8, 2010 in Cupertino, California. Jobs announced the new iPhone OS4 software. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

Apple

Apple was founded back in 1976 by Steve Jobs, a canny marketer, and Steve Wozniak, an unparalleled programmer and computer genius. They had early successes in personal computers with the Apple I and the Macintosh, but by the mid-’90s they’d petered out, seemingly much more interested in appeasing shareholders than the public. Did you know Apple made CD players for a while? Digital cameras? A lot of people don’t remember Apple’s “weird” period.

But let’s single out the the Apple Newton. This PDA (personal digital assistant) nearly bankrupted the company in 1993 after being rushed out before it was ready; it’s handwriting recognition feature could barely read anything other than block letters and was widely mocked. Hold that thought for a paragraph.

Around 1997, Steve Jobs returned to the company and decided to concentrate on what the company did best: personal computing that catered to regular day-to-day users rather than avid tech professionals. He began to cater to different groups with singular products. The PowerMac for pro users. The iMac for classrooms. The MacBook and the MacBook Pro for people working out of coffeeshops.

But then Apple created the iPod, which could hold an entire library of music in your pocket. It was followed by the iPhone… a landmark device that put the internet, colors and all, in your pocket. The iPhone, funnily enough, has huge similarities to the much maligned Newton. Now consider the iPad and the Apple Pencil and how their handwriting recognition technology is considered the best in the industry. Sometimes you have the right idea but just 20 years too soon.

Then there was the iTunes store, which took over the music industry. Then the App Store, which transformed the tech ecosystem. In August of 2018, they became the most valuable company in the world with $1 trillion in value.

Which is still pennies compared to the Dutch East India Company. But hey. Who’s counting?