How the Marshall Plan helped avoid World War 3

We’re all too familiar with the apocalyptic tales, horrendous death tolls and inhumanity that was exposed during World War II. From the far reaches of the Pacific Islands to the heart of Europe, WWII left no corner of Earth untouched and its wake is still evident in how the world is organized today.

The United States of America’s gallant war efforts is the stuff of legend and fills our history books and television screens. But as victor of WWII, America also set out with its allies to rebuild the broken world.

Through the combined efforts of the Marshall Plan, Western Europe was brought back into action by the end of the decade. The subsequent occupation of Japan led to the eventual rebuilding of the entire country. Today, the United Nations stands as a valiant reminder of the need to honor diplomacy over all-out war. America’s most positive influence on the world has been through diplomatic foreign policy.

Revisiting the Marshall Plan

Due to a number of factors, America emerged as an economic powerhouse after the war ended. While many countries in the main war zones were left decimated, the infrastructure and financial system was left intact back in the States. As one of the richest nations in the world, it issued a financial aid program for Europe titled the Marshall Plan.

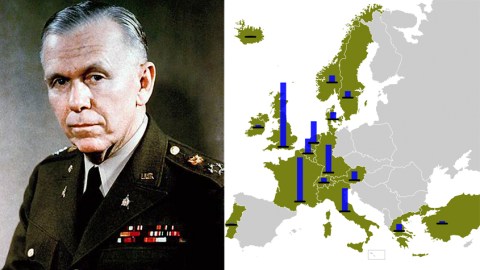

Former general and and esteemed statesman, Secretary of State George C. Marshall spearheaded the plan that was given his namesake. On June 5, 1947 he gave a speech outlining the European Recovery Program (ERP)—the official name of the Marshall Plan.

Marshall presented the plan to the American people and to legislators in Congress. Poor post-WWI diplomatic relations had been one of the main causes for the eruption of World War II. Circumventing these types of foreign policy mishaps was paramount if humanity were to maintain relative global peace during this time. A lot of this was due to American isolationism and the disaster of the Treaty of Versailles, which saw the failure of the League of Nations to materialize, embittered nationalism being fueled and Americans opting out of further diplomatic relations, which led to the violent breeding grounds for WWII.

Marshall touched upon this during his speech at Harvard:

“Aside from the demoralizing effect on the world at large and the possibilities of disturbances arising as a result of the desperation of the people concerned, the consequences to the economy of the United States should be apparent to all. It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace.

“Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist. Such assistance, I am convinced, must not be on a piecemeal basis as various crises develop. Any assistance that this Government may render in the future should provide a cure rather than a mere palliative.”

Roughly $12 billion (~$126 billion in 2018 dollars) was spent to facilitate this effort in 17 European countries. The program started in April 1948 and spanned for four years.

In 1953, Marshall was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. While these diplomatic efforts paid off, the post-WWII era was not without its fair share of problems. The breakdown of foreign policy between America and its strongest ally in the war, the Soviet Union, led to the Cold War and many subsequent proxy wars.

Left: A map of former Eastern Bloc countries. Right: Joseph Stalin, ruler of the Soviet Union from 1922 to his death in 1953. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons)

In direct contrast to the United States’ post-war efforts, the Soviets instead demanded reparations from their occupied countries. The Soviets and Eastern Bloc countries turned down the economic aid offered by the United States as part of the Marshall Plan. This outright denial fostered a further divide between the two differing philosophies of governance.

While this was occurring in the post-war theater of Europe, Japan was in the midst of its own kind of revival.

American occupation and rebuilding of Japan

In September, 1945, General Douglas MacArthur was tasked with taking control over the Supreme Command of Allied Powers (SCAP). Along with the occupation of Japan, they took charge with the work of rebuilding Japan. The United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and Republic of China were all part of the Allied council, but in the end it all came down to MacArthur who had the final decision.

General Douglas MacArthur signs as Supreme Allied Commander during formal surrender ceremonies on the USS MISSOURI in Tokyo Bay. Behind General MacArthur are Lieutenant General Jonathan Wainwright and Lieutenant General A. E. Percival. (Public domain)

The process of rebuilding Japan occurred in three phases over roughly five years until 1950. With complete dominion over the defeated country, the Allies punished Japan by convening for war crime trials in Tokyo. The Japanese Army was dismantled and former military officers barred from running for political office in the newly formed government. This also eliminated non-defensive military forces and any right to wage war. SCAP also led many economic reforms that benefited low-income tenant farmers and helped break up Japanese business conglomerates. It also successful in relegating the emperor’s status to something of a figurehead who had no control over the nation. The parliamentary system was built from the ground up.

Over the years many wartime companies shifted into a peaceful economic focus. These Japanese private companies were able to expand quickly and abided by the full support of Allied forces. Companies such as Toyota, Nissan and Mitsubishi all were early upstarts here. Throughout the years, the efforts the Japanese had once so ferociously dedicated to war had been completely switched to new peaceful economic development. Old weapon factories began to produce cameras and the devastation of the infrastructure led to rapid advancements in technology.

On a global scale, these changes were met with opportunities for trade and cheap materials. America had now become one of Japan’s greatest allies. As the looming threat of communism creeped up on the West, priorities had changed drastically in less than a decade. Even the remilitarization of Japan was no longer seen as a problem to the U.S. Positive economic foreign policy had superseded the wounds of WWII.

It was during the Korean War that Japan became a central supply depot for UN forces for the United States. This was just a sign of things to come and the power that the newly created UN would have over future world affairs.

The United Nations emerges from the rubble

It’s somewhat fitting that out of the worst war to ever strike the world, we developed some of the most cohesive foreign policies that led the way for a newly globalized society. President Franklin D. Roosevelt felt that the U.S. refusing to be a part of the League of Nations contributed to the shaky circumstances that led to WWII breaking out. At the time of the United Nations creation, he believed that the UN would serve as a new post-war system and would ensure world security backed by the strongest nation on Earth.

In a radio address on United Flag Day, June 14, 1942 Roosevelt stated:

“These freedoms are the rights of men of every creed and every race, wherever they live. This is their heritage, long withheld. We of the United Nations have the power and the men and the will at last to assure man’s heritage.”

The United States was responsible for contributing 40 percent of the UN budget. The headquarters was created and established firmly in the United States in New York City. It was within this system that the United States showed its acumen for worldwide foreign policy. The UN’s charter strives for conflict prevention, a basic upholding for human rights, worldwide cooperation and international social and economic progress.

This was a time when the United States set the precedent for what it meant to be a world leader, led by diplomatic restraint. History is showing that the U.S. had its greatest successes with diplomacy, while military interventions with non-allies land the nation and the world into hot water.

—