Why “linguistic similarity” is so often the key to success

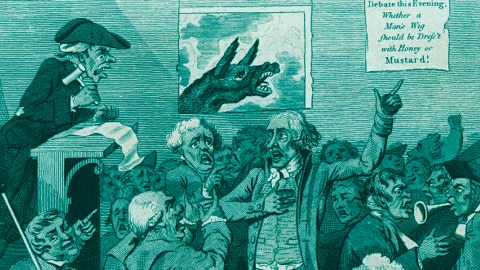

Credit: Isaac Cruikshank / Public domain / Wikimedia Commons

- The use of language in the workplace provides a fascinating window onto organizations and industries.

- To study the link between language and success at work, a team of scientists looked at office emails.

- Employees whose linguistic style was more similar to their coworkers’ were three times more likely to be promoted.

Organizational culture has become a hot topic. Building a strong culture, maintaining it, and hiring applicants who fit.

But what is organizational culture exactly? Beyond some vague notion of beliefs and values, can it actually be measured? And does fitting in with organizational culture have implications for how well people do at work?

Just like online beer communities have terminology and linguistic norms, so do organizations. Different tribes have different lingo. Startup founders talk about “pivoting,” retailers talk about “omnichannel,” and Wall Street traders talk about “pikers” and being “junked up.”

But beyond slang and terminology, there are other ways organizations or industries use language differently. Some may tend to use shorter, more clipped sentences, while others may use longer ones. Some may use more concrete language while others may talk more abstractly.

To study the link between language and success at work, a team of scientists looked at a data source we don’t usually think much about: email. Unlike RateBeer users, employees don’t write online reviews. But they do write emails. Lots of them. Emails asking colleagues for information and emails providing feedback on others’ work. Emails sharing drafts of presentations and emails scheduling a time to meet with a client. Thousands of notes about every topic imaginable.

Just for fun, take a minute, open your “Sent Items” folder, and scan what’s inside. It might seem like normal work and personal stuff. Trivial even. And it often is. But it’s not just any work and personal stuff. It’s your work and personal stuff.

Those notes about the headers on a particular document or what image should go on page 23 of a PowerPoint deck might seem insignificant, but they provide a snapshot of what’s going on in your work life. Not only the progression of various projects and decisions, but how you have evolved as a colleague, leader, and potentially even friend. They’re pottery shards or remnants of that ancient civilization that is you at the office. And consequently, they provide a lot of information about you and how you have, or haven’t, changed over time.

The scientists looked at five years of data, more than 10 million emails sent between hundreds of employees of a midsized firm. Everything Susan in Accounting sent to Tim in HR and everything Lucinda in Sales sent to James in R&D. And rather than looking at how many emails were sent, or who the emails were sent to, the researchers looked at the words each employee used.

But this is where the study gets even more interesting. Because rather than focusing on the content of what employees talked about (e.g., document headers or PowerPoint slides), the researchers zeroed in on something completely different: employee’s linguistic style.

When reading an email, talking on the phone, or considering any type of communication, we tend to focus on its content. If someone asked you to look at your email and report back on the language used, you’d probably focus on the main topics. There were a bunch of emails about this meeting, others about a particular project, and a few regarding that big retirement party you’ve been planning for a coworker.

All these are examples of content. The subject matter, topic, or substance of what was being discussed.

But while content is clearly important, there’s another dimension that often goes unnoticed: linguistic style. Consider the phrase “They said to follow up in a couple weeks.” The content (following up in a couple weeks) provides a sense of what is happening, but embedded within the content are words like “they,” “to,” and “a.”

These pronouns, articles, and other style words often fade into the background. We often don’t even notice that they are there. In fact, even after I mentioned them, you probably had to look closely to find them in the sentences. They’re almost invisible. People gloss over them as they jump between the nouns, verbs, and adjectives that make up the linguistic content, or what was said.

But while they’re often ignored, style words actually provide a lot of information. Communicators have only so much flexibility in the content they’re communicating. If someone asks when a client said to follow up, and the answer is “In a couple weeks,” some version of those words is probably needed to communicate the idea.

But how we communicate that idea is up to us. We could say, “They said to follow up in a couple weeks,” “Following up a couple weeks from now would be good,” or any number of variations. And while these differences might seem minor, because they reflect how people communicate, they provide insight into the communicators themselves. Everything from personality and preferences, to how smart people are and whether they are lying.

The researchers analyzed employees’ linguistic style. In particular, how similar people’s linguistic style was to that of their coworkers. Or, said another way, their cultural fit. Whether employees used language the same way as others around them. Whether someone used personal pronouns (e.g., “we” or “I”) when communicating with colleagues who used them a lot or used articles (e.g., “a” or “the”) and prepositions (e.g., “in” or “to”) to a similar degree as their peers.

The results were remarkable. Similarity shaped success. Employees whose linguistic style was more similar to their coworkers’ were three times more likely to be promoted. They received better performance evaluations and higher bonuses.

In some ways, this is great news. If you fit in well at your new job, you’re likely to do well. But what about everybody else? What happens to people who don’t fit in? Indeed, people with a dissimilar linguistic style weren’t so fortunate. They were four times more likely to be fired.

Fit isn’t something we have to be born with, we just have to be willing to adapt over time.

So are people who don’t fit in from the get-go just destined to fail? Not quite. Because rather than just studying whether employees fit in initially, the researchers also examined how their fit changed over time. Whether some employees were more adaptable than others.

Similar to the beer community, most new hires adapted quickly. After a year at the firm they had acclimated to the organization’s linguistic norms.

Not everyone, however, adapted to the same degree. Some adapted more quickly while others adapted more slowly. Adaptability, in turn, helped explain success. While successful employees adapted, those who would eventually be fired never did. They started with low cultural fit and slowly declined from there.

Linguistic similarity even helped distinguish between employees who stayed at the firm and those who left to pursue better options. Not because they got fired, but because they were offered something better elsewhere. These folks assimilated early on, but at some point, their language started to diverge. While clearly capable of adapting, eventually they stopped trying, foreshadowing their intention to quit.

Adaptability ended up being more important than initial fit. People who were a good fit initially did do well, but those who adapted quickly to the changing norms were even more successful. Fit isn’t something we have to be born with, we just have to be willing to adapt over time.