“When you’re furious get curious”: How to handle emotional hijacking

- Curiosity killers are situations that make staying open-minded and asking questions a real challenge.

- Strong emotional reactions can limit useful responses to a situation we perceive as stressful or threatening.

- To re-engage with curiosity, it helps to step away, take some breaths, and question what you may be missing.

While curiosity is almost always the right choice, it’s often not the easy one. I find questions most effective when I work through them with another person. However, I’ve noticed some situations when staying curious is particularly hard. Call these curiosity killers.

In the experience of Jamie Higgins, an executive coach to top leaders throughout corporate America, [emotional hijacking] is by far the most challenging of all the curiosity killers. When we get emotionally activated — quite common when people are telling us things we need but might not want to hear — we face a choice: We can reactively race to the top of our ladders, or we can notice our reaction and use it as a cue to slow down and choose curiosity. With practice, negative and uncomfortable emotions can become gateways into strengthening our curiosity and deepening our learning from others.

I faced this choice when I heard, secondhand, that one of my junior teammates, Bailey, had declined to take on a project that I felt I needed him to do. Blood rushed to my head so fast that I’m lucky a vein didn’t burst. Here I was, tired from working so hard and making painful personal trade‐offs for the good of the organization, and Bailey came back with what sounded like a, Thanks, but I’ll pass.

How dare he be so selfish when we’re all making sacrifices, I fumed inside my head. And if not Bailey, who? Who was going to get this done? I was ready to scream. While venting to my co‐founder, Aylon, he nodded and commiserated — but then calmly suggested that my, ahem, strong reaction might be worth getting curious about. What was going on inside me that had made Bailey’s response so triggering?

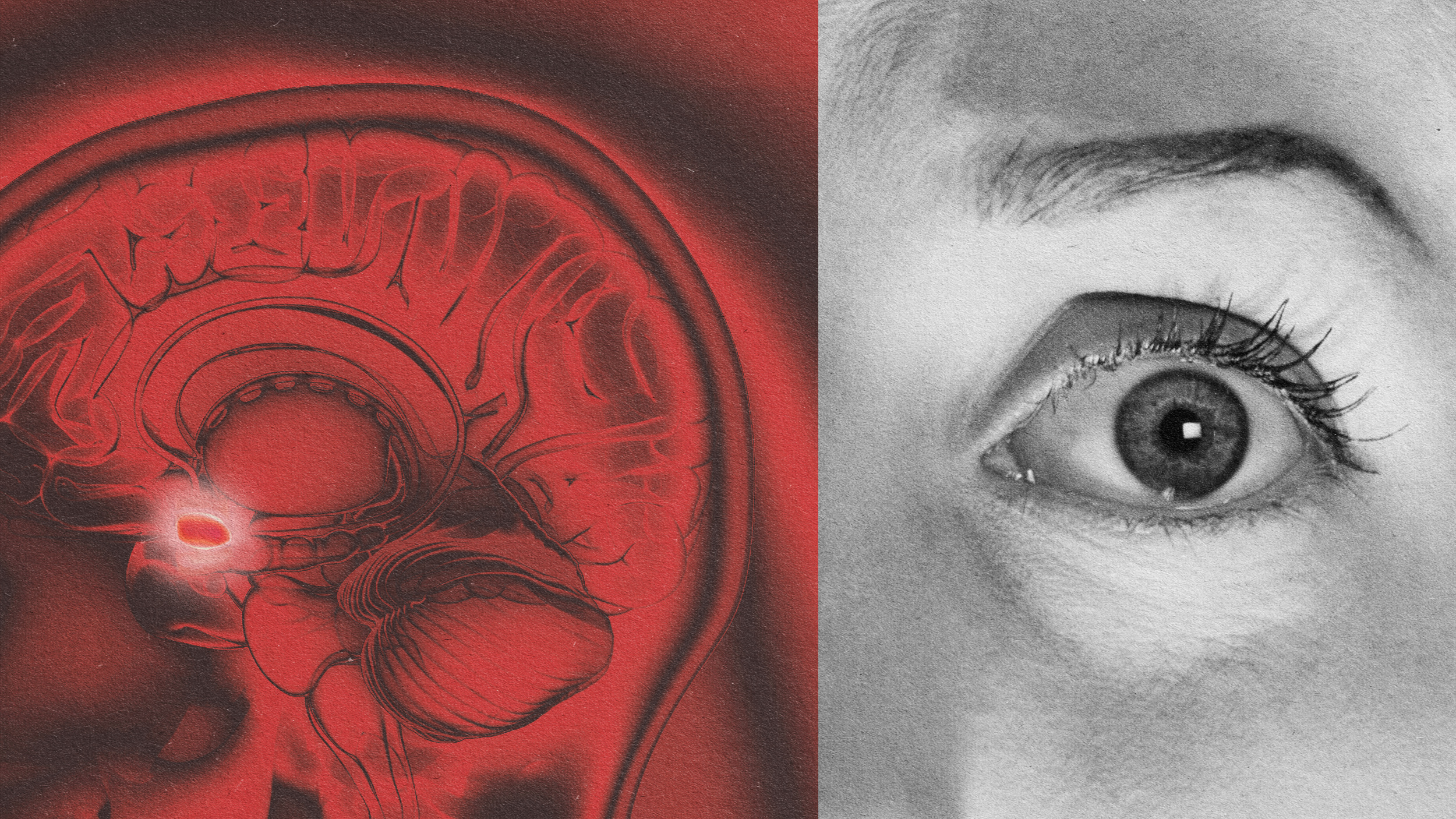

Strong emotional reactions result when we perceive danger — for example, a threat to our status, our beliefs, our identities, or our resources, including time, money, and energy. This process is known as an “amygdala hijack” because the part of our limbic system responsible for processing our emotions takes over our thinking mind (our prefrontal cortex). We might fight (get defensive), flee (avoid the conversation, change the topic), freeze (clench up and shut down), or fawn (people‐please, sugarcoat, smooth over). This response narrows our attention to the immediate threat at hand, whether perceived or real, and makes it near impossible for us to broaden our awareness to things like the other person’s experience or the possibility that we are missing important information.

In other words, when we feel threatened, our curiosity engine shuts down. What’s worse, this can quickly spiral into a vicious cycle, since when we are less curious, we are more likely to become emotionally rigid, more attached to a particular outcome, and more fearful of something not going right, all things pretty much guaranteed to shut down learning.

But what if we could flip this on its head? What if the emotions, instead of shutting us down, could become curiosity cues? Beyond the knee‐jerk reactions of fight, flight, freeze, or fawn lies the possibility of a fifth F: entering the find out mode, in which we get curious about our own reactions.

It’s not easy, and it takes time to learn, but it’s absolutely possible if we’re intentional about it. [One of my favorite bosses at Monitor] Jim Cutler told me that he learned to notice and respond to the physical cues of powerful emotions — for example, when he can sense anger or frustration building up in his body. Now, before his hand pounds the table, he takes a deep breath, notices the emotions, and reminds himself to be curious.

What if the emotions, instead of shutting us down, could become curiosity cues?

Jeff Wetzler

Practices like mindfulness or breath work can also help us get the distance we need from our reactions so that we can notice them arising and then get curious about them rather than being consumed by them. And in the meantime, for the rest of us mortals who haven’t yet reached a sufficient level of self‐awareness, that’s what friends and mentors are for (see also: therapists). We can ask them to help us talk it out — not just to empathize and tell us all the ways we’re right but also to help us get curious, just as Aylon did for me when he noticed me getting so worked up about Bailey.

After Aylon’s nudge, and a few beats, I was able to say to myself, “That pissed me off, maybe more than was called for. What nerve did he hit?” Perhaps my own exhaustion and the personal sacrifices I’d made for work had taken such a toll that I could not be sympathetic to anyone who would draw different boundaries. Perhaps I was more power hungry than I would like to admit and was therefore incensed when someone I employed would say no to my requests. Perhaps I was just too rushed and stressed to be willing to consider that Bailey might have a justifiable reason to say no.

Now that I wasn’t stuck in fight, flight, freeze, or fawn mode, I could find out: What am I missing here? As I pursued that question, I discovered that Bailey had said no for an excellent reason. He wasn’t prioritizing himself over the team. He wasn’t rejecting my authority. He wasn’t any of the worst things my emotionally hijacked brain had jumped to. When asked, he explained that he had already committed to other important projects during the time I needed his help, and he didn’t want to under‐ mine that equally important work. When he walked me through his other commitments, I saw he was right. If I hadn’t chosen curiosity, I might have wrongly undervalued a teammate for making a decision in the best interest of the organization. As Radical Candor author Kim Scott shared with me, “When you’re furious, get curious.”