Use the “Johari Window Model” to improve your conversations

- Whenever we go into a conversation, we often assume certain things about what our partners know and don’t know.

- The Johari Window Model is a useful tool to reflect on how others see the world and can help to avoid miscommunication.

- Here we look at three practical ways we can apply this model to our daily working lives.

I’m not a DIY kind of person. Growing up, I gravitated to books more than making things. When presented with an IKEA instruction manual, I clam up. I bash, screw, and twist things in the hope that they will stay up.

Occasionally, a carpenter or builder will come to our house. They’ll do some kind of diagnostic on the job and then corner me. “Well,” they’ll say, “we’ll probably have to use 2×6 kiln-dried lumber with structural sheathing for the load bearing walls.” He’ll tap the wall and wait expectantly for me to reply. Of course, I have no idea what to say. He might as well have spoken Elvish.

The problem is that when we go into conversation with someone, we each have certain assumptions about what the other speaker knows. A conversation — especially in its early stages — involves a kind of mutual weighing up. We test and probe to see how much the other person knows and how much we should assume. Sometimes, we get this wrong. As with my overly informative builder, we misjudge someone’s base knowledge. But what if there was a good way to avoid this kind of miscommunication? What if there was more of a rulebook to the assumptions?

Well, that’s called the Johari Window Model, and learning about it can change how we approach every aspect of our interpersonal lives.

The Johari Window Model

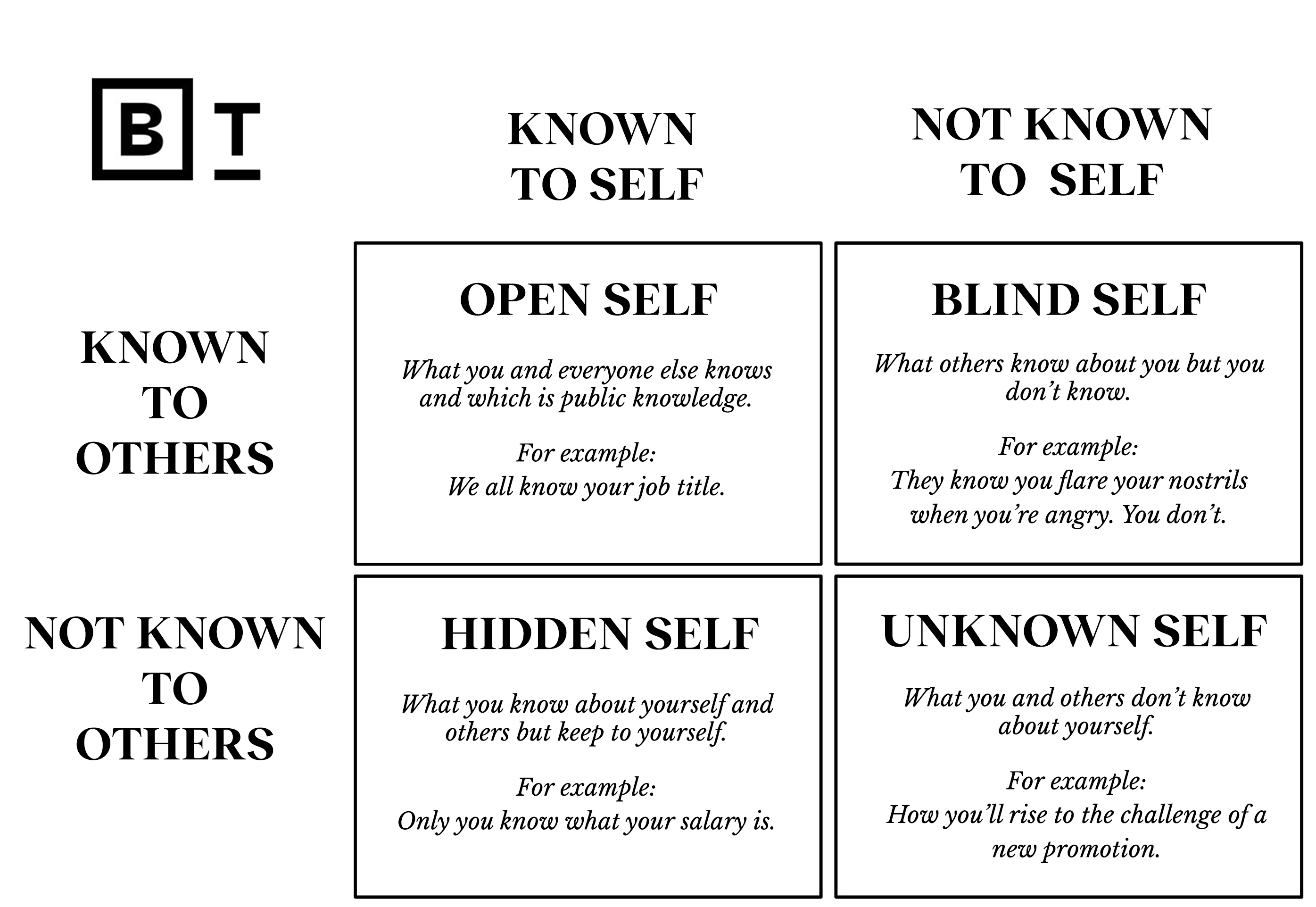

The Johari Window Model goes back to the mid-20th century work of psychologists Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham on better practices in self-help discussions — “Johari” is a commingling of letters in their names. They wanted conversations to be open and meaningful. The general idea is that we identify someone as belonging to one of four different starting points in what they know. These are the four base positions for anyone’s existing knowledge. When we open a conversation, we have to establish which of the four our interlocutor belongs in.

First is the open self. This is what you know and everybody else knows, which is public knowledge. For example, we all know your job title or that Jonny writes brilliant articles.

Second is the blind self. This is where others know something about you but you don’t know. For example, everyone knows you flare your nostrils when you’re angry, or my editors know I always make the same, ridiculous errors.

Third is the hidden self. This is what you know about yourself and others, but keep to yourself. For example, only you know what your salary is, or only I know what I’m buying my editors for Christmas.

Fourth is the unknown self. This is what you and others don’t know about yourself. For example, how you’ll rise to the challenge of a new promotion.

Not only does the model provide us with a good label to apply to ourselves and others in a conversation, but it’s also a good starting point to reflect on the mindset of who we are speaking to. It’s a useful tool or invitation to empathize with others and see the world — and the conversation — as they do.

Theory into practice

The problem with models is that they might be great in theory, but how can we make use of them? A great many organizations and academics put good stock in the Johari Window Model, but how can we apply it to our daily lives? Here are three ways.

Everyone needs an editor. There is a wise and old principle that “every author needs an editor.” Whether you’re Stephen King or Agatha Christie, you need an editor. An editor is not simply a grammatical maestro; they’re a fresh pair of eyes. An author can often spend so long on their own text or plot that they miss obvious things. An editor is there to point those things out. Likewise, in our jobs, we can spend so much time on a task that we start to miss obvious things. You might have spent weeks on a presentation and forgotten the key point, or you might have obsessed over a tiny corner of a logo to miss the glaring typo in the picture. It’s not just authors who need an editor; it’s everyone.

Framing the right questions. In a corporate setting, miscommunication often arises when assumptions are made about what others know or understand. By carefully crafting questions, we can reveal hidden information and clarify uncertainties. The easiest way to do this is to ask open-ended questions like, “What are your thoughts on the project goals?” or “Do you see any challenges we might have overlooked?” Managers invite team members to share insights and concerns that might otherwise remain unspoken. Another rule of thumb, especially in a team meeting, is to rarely talk for too long without leaving space for questions and for others to share what they do and don’t know. I’m probably not the only one to have sat through an hour-long monologue and been lost in the first five.

From hidden to open. So much of the success of a conversation depends on how open and honest we are with each other. Often, we find it hard to share what we know from either fear of appearing ignorant or feeling uncomfortable around someone. You will have a far more “open self” with your best friend than a new boss. An important step, then, for any manager is to establish a space where people feel they can move from hidden to open. It’s about creating a trusting, safe environment where people feel comfortable revealing themselves. Over on Big Think+, the TV personality and talk show host, Tavis Smiley, offers his advice about how to create just that — it’s about listening generously. As Smiley puts it, “that means sometimes listening not with your head, with your ears, but with your heart.” You have to give a bit to get a bit. You have to open yourself so you can invite others to follow suit.