How the “porcupine dilemma” teaches us to cooperate like champions at work

- The “porcupine dilemma” is a metaphor Arthur Schopenhauer first used to explore the fact that humans both crave and resist being near one another.

- In the 20th century, Sigmund Freud repackaged the idea to explore how we view strangers on first impressions.

- Here we look at three ways the porcupine dilemma might apply to our daily lives.

“Barnum statements” — named after 19th-century showman P.T. Barnum — are the kind of statements with which almost everyone agrees. They’re loved by soothsayers, clairvoyants, and mentalists the world over because they make it seem like you know what someone is like. Horoscopes are almost entirely written in Barnum statements.

“Avoid health risks today.”

“A project you’ve been working on will be coming to an end.”

These are examples of Barnum statements. Who wants to risk their health? Who isn’t working on some project?

One of the most common examples of a Barnum statement is: “Sometimes, you are sociable and outgoing. At other times, you like to be alone and enjoy your own company.” Well, yes. That applies to almost everyone living on our planet. It gets to the heart of one of the most fundamental paradoxes of the human condition: We are social animals who also like to hide in dens. We’re chittering meerkats one day and hibernating bears the next.

This is known as the “porcupine dilemma” and it comes to us via Arthur Schopenhauer and later by Sigmund Freud. It reveals something fundamental about the human condition and teaches us a great many things about how to live well.

The paradox of other people

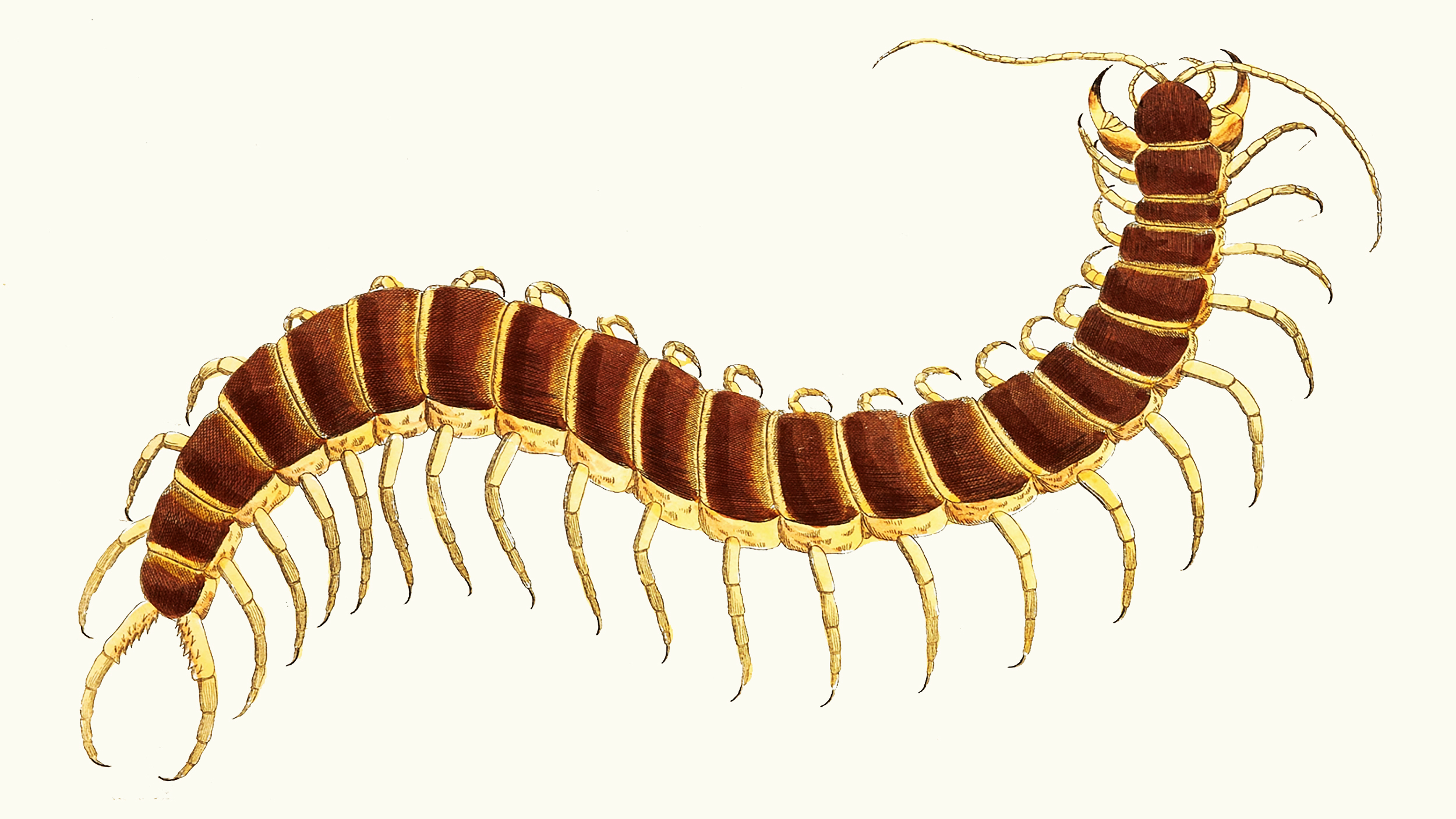

Imagine two porcupines, cold and shivery, trying to keep warm on a frost-biting night. They huddle together to share their warmth, but as they do, they prick each other. Half of the evening is a spiky dance, as the porcupines oscillate between “shared warmth” and “painful pricks.”

For Schopenhauer, almost all our relationships are like this thorny tango. We want to be around other people. We like to laugh, gossip, and dance, and other people offer us consolation and love. And yet, people can be exhausting. They can be unbelievably annoying. Sometimes, we just want to retreat into the bubbled comfort of our home and talk to absolutely no one.

In Freud’s somewhat more fervid language, whenever we meet someone, we are immediately caught in tension. On the one hand, this person might be “a potential helper or sexual object,” but they could also be a rival or aggressor. In other words, we can have sex with or fight everyone we meet. Other people can be both a source of support and abuse, often within the same half hour.

The porcupine dilemma is a useful way to reflect on a relationship. Sometimes a relationship can feel overbearing and suffocating. It can tire you out. At other times, relationships can give light to life. For Schopenhauer and Freud, it’s all about the size of your spikes.

Lessons from the spiky fringe

If we accept that something like the porcupine dilemma is true for most people, what can we do about it? What can we learn from the spiky fringe? Here are three work-life suggestions:

Respect boundaries. In the workplace, much like our porcupines looking to get warm, we all need collaboration to foster teamwork and make our jobs generally easier. However, respecting personal boundaries is necessary if we are to avoid conflict. All teams have to walk the fine line between working closely and not cramping each other out. In 2018, Bernstein and Turban authored an interesting, counterintuitive paper which showed that open office layouts actually decreased the number of face-to-face interactions between colleagues. They theorized that the forced collaboration of an open office actually “triggered a natural human response to socially withdraw from officemates and interact instead over email and IM.” In other words, open offices force porcupines too close together, and they run away to safety.

Recognize remote space. Respecting boundaries is not just a thing for physical, brick-and-mortar offices but is equally true for remote working. An empty calendar isn’t an invitation to arrange a meeting. A green button and “online” sign don’t mean you need to send someone a message. Give people space. Let them do their job. In recent years, there have been a series of studies that show that while remote working can make people happier, it also depends on how well boundaries between work and home are managed, both by individuals and the organization.

Create a support bubble. Sometimes, despite the best office plans and workplace policies, a day at work can grind you down. It can feel like you’ve done nothing but talk in business jargon for eight hours straight. It can feel like you’ve been pricked and spiked enough for a year. In these moments, we need to establish a kind of recovery space. We need to decompress and balm our sore, swollen wounds. In an interview for Big Think+, the actor, writer, and director Jesse Eisenberg talks about how important his “bubble” is. As he puts it, “I really don’t like to talk about the industry that I’m in because I find, in some ways, you can never turn it off… And so I surround myself with people who do different things.” Set up a support bubble, which is not work-related at all. Talk to your loved ones about sports, movies, books, gardening, or the latest family gossip. It doesn’t matter what you talk about; turn off the business mind. Find people who are not porcupines.