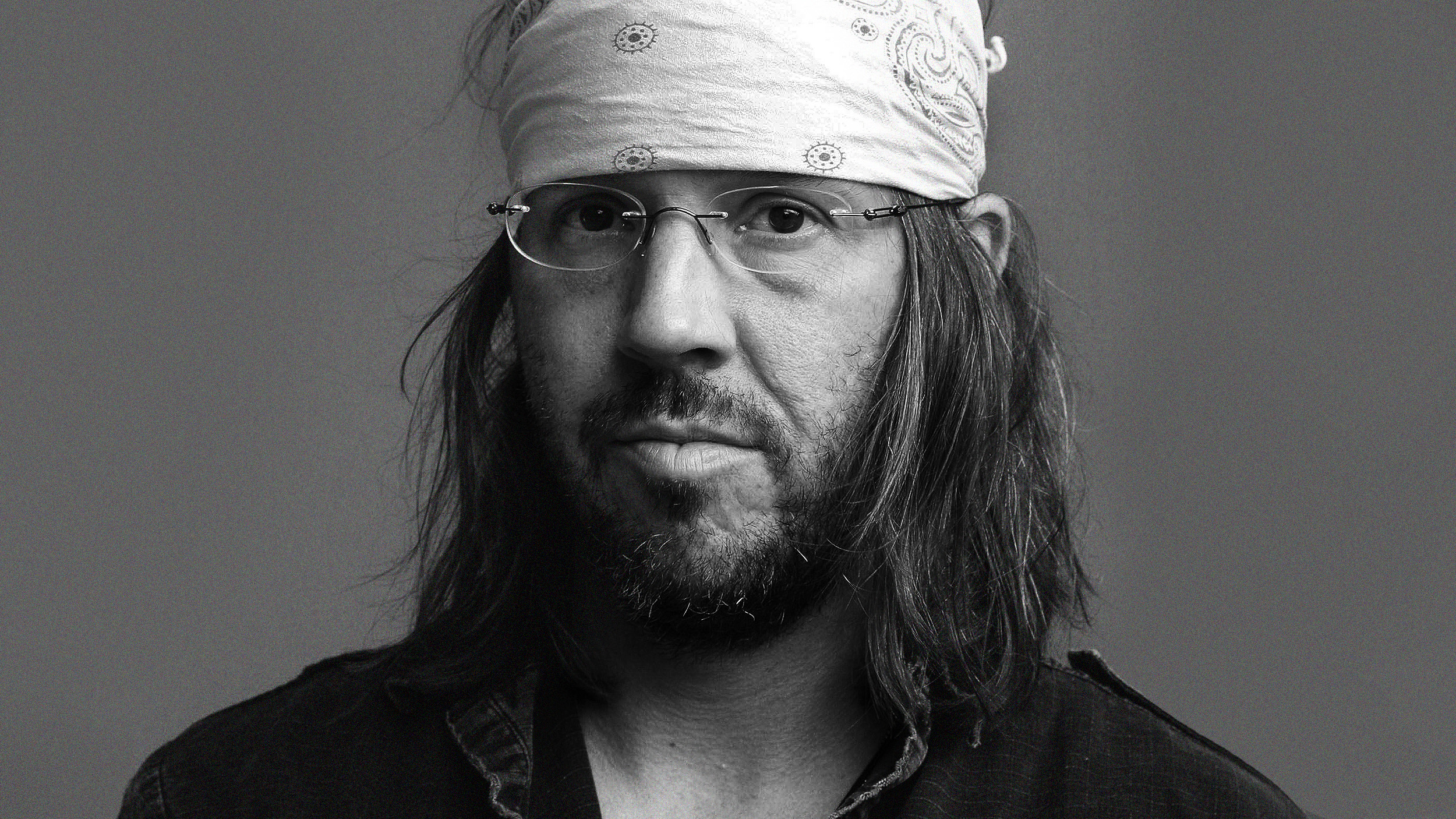

Jesse Eisenberg’s leadership secret: Embrace your anxiety

- Leaders often struggle with imposter syndrome and fear that they are failing.

- Eisenberg wants everyone to know that those fears are normal; even the most talented people experience them.

- To handle those emotions, leaders must learn to accept them, redirect them, and nurture conditions for effective collaboration.

Earlier in his career, Jesse Eisenberg was on the set of the movie Adventureland (2009) when he suffered a panic attack. He felt his breath racing, his mind going blank, and his body shutting down. An entire crew of professionals on set, a production with deadlines, and he had to ask if they could stop filming.

By his own admission, the scene wasn’t complicated. His character, James, was saying goodbye to his parents before moving to New York City. In a coming-of-age romantic comedy like Adventureland, you don’t get more by the numbers than that. Even so, he froze.

The director, Greg Mottola, told everyone to take a break and took Eisenberg aside. He said, “I just want to let you know that not only do I understand what you’re experiencing, but I’d be surprised if you didn’t experience it all the time. You’re doing a job that’s emotional, that’s demanding, yet you’re also worrying if your hair looks dumb. I can’t understand how anybody does your job. I certainly would never be able to.”

Eisenberg says this example of stellar leadership proved cathartic. He returned to the set, and rather than try to achieve a false perfection by ignoring the difficulties of his craft, he chose to accept them and used them to motivate his performance. He finished the scene (and the rest of the movie, too).

Since then, Eisenberg has become an author, been nominated for an Academy Award, and made his directorial debut with the 2022 film When You Finish Saving the World. Through it all, he’s taken Mottola’s lesson with him and evolved it to discover how to lead through anxiety, navigate fears at work, and help others do their best.

In an interview with Big Think+, he shared some of the strategies he has developed along the way.

Accept fear and anxiety

“Probably it’s important to dispel the myth that actors are full of themselves, and they must be so confident all the time,” Eisenberg tells Big Think+. “I cannot underestimate how often I’m driven by anxiety and fear.” The same should be said for leaders in any field.

Eisenberg points out that many of the most creative and talented people he has met experience the same fears and anxieties he did that day on set. Despite the awards, accolades, and years of success, they still worry that past successes don’t guarantee future ones. Maybe this time, they’ll be outed for the imposters they truly are. Maybe this job, project, or venture will be their last.

Rather than wallow in those fears and let anxiety lead to unproductive habits, Eisenberg has learned to accept them as a normal part of wanting to do a job well.

“It’s helped me because I’m no longer denying the feelings that I’m having and I’m no longer terrified that I might have a feeling,” he says. “Once you stop denying the feelings that you’re having [you can] try to redirect them to a healthy outcome. You don’t worry as much.”

Reframe and redirect

Even when accepted, fear and anxiety still don’t feel great. As such, Eisenberg recommends channeling that adverse energy to power something positive.

The first step is to reframe. While we label these emotions “negative” because of how they feel to experience, Eisenberg reminds us that they often have an admirable context: passion. We don’t grow anxious when doing something we don’t care about. We do it and check it off our to-do list. It’s only the things we want to do right that stir up those uneasy feelings. And that applies to any job or project, even ones that may seem rote or perfunctory.

“Whenever I’m having those feelings of great discomfort or worry,” Eisenberg says, “I take a second, breathe, and remind myself that this anxiety comes from a place of really investing in what I’m [doing].”

The next step is to redirect those fears and anxieties into something useful. When Eisenberg suffered from stage fright very early in his career, an acting coach advised him to channel those feelings into his performance. Even if the character brimmed with confidence, beneath the swagger, he might be panicking that things won’t work out. That allowed Eisenberg to add depth to his performance.

Different jobs and professions will require other strategies, so experiment with different tactics. Once you find something that works, you’ll find you can use your fears and anxiety to motivate, rather than hinder, your efforts.

Don’t pop your bubble

Another potential source of fear and anxiety is the aspects of your job you can’t control. Usually, these come from other people and outside forces. Will clients like your idea, product, or pitch? How will they react? Will the market create unexpected headwinds? Questions like these will often feed self-doubt, too.

Eisenberg manages this self-doubt by creating what he calls his “bubble” — that is, an environment where he can do his best work. As an actor, major sources of self-doubt can be critic reviews and self-criticism from watching past performances. Eisenberg shuts these out.

“It sounds strange, but I don’t watch the movies I’ve been in. I don’t read any reviews,” Eisenberg says. “I am most effective by not thinking about that stuff, by not becoming obsessed with something that I can’t control so I can kind of focus on the work that I’m doing.”

Another self-imposed habit is that he doesn’t talk shop off the clock. Instead, he surrounds himself with people who do different things and engages with them about their jobs, hobbies, and so on. At home, for instance, he prefers to talk with his wife about her social service and education work, which he finds to be wonderful and interesting.

He adds: “Maybe [this bubble] comes from a place of fear or weakness, but it’s the only way I can self-motivate.”

Collaborate to ease imposter syndrome

A common fear among leaders is the expectations of others. Leaders can come to believe that others expect them to have all the answers or that they can only lead if they are the most talented, intelligent, and impressive person in the room. Otherwise, everyone will see you for the imposter you feel you are.

None of that is true, by the way. However, those beliefs can lead to unhelpful leadership strategies such as either micromanaging your team or not providing them enough support.

Instead, the mark of a true leader is their ability to create the conditions necessary for a team of people to collaborate effectively. Eisenberg learned this lesson when he worked with Julianne Moore, an Academy Award-winning actor he describes as “unbearably talented.”

“I cannot underestimate how often I’m driven by anxiety and fear.”

Jesse Eisenberg

When they began working together, Eisenberg was intimidated by the idea of directing an actor of such esteem. He worried that with her years of experience, she would easily recognize him as a fraud, so he avoided giving her direction or feedback. Eventually, he had to offer some notes — it’s the job after all — and he found that that’s exactly what she wanted. They workshopped new approaches. They had healthy disagreements. They had fun.

“I discovered that being in a position of intimidation with a colleague is not a sustainable place,” Eisenberg says. “I think [she] is more talented than me. I think she’s a better actor than I’ll ever be. But those thoughts were not helpful.”

Scene One, Take Two

On the second day on the set of When You Finish Saving the World, Eisenberg was shooting a monologue with Finn Wolfhard, an experienced actor best known for his role in Netflix’s Stranger Things. Eisenberg took Wolfhard aside and asked him how he was doing. Wolfhard admitted he had a rough night as he had been panicking over the day’s scene.

And Eisenberg gave Wolfhard some familiar words of encouragement:

“Listen, I understand what you do. I understand it can be difficult. I understand you’re putting yourself out there emotionally while also trying to remember three pages of dialogue while also worrying that the makeup that you’re wearing makes you look vain. Finn, I just want to tell you what I heard from a wonderful other director: All of that’s normal. The fact that you don’t feel that every second is probably a miracle. When you do feel it, use it! Have it be part of the scene.”

As Mottola did all those years back, Eisenberg used his position as a leader to normalize those common human experiences. In doing so, he not only gave permission to his team to feel and work with “negative” emotions. He offered himself permission to do the same.