How Bill Gates cemented the folkloric status of the “nerd founder”

- The “lonely-nerd-turned-accidental-billionaire” story is a cornerstone of modern American success.

- Bill Gates became the epitome of the “nerd founder” when he saw a commercial market for software where none existed.

- A year after Microsoft went public in 1986, Gates became America’s youngest billionaire. He was 31 years old.

In the wee hours of the night, two young men are writing code, their faces pale in the blue light of the room. They haven’t taken a break in hours. One of them—his sandy brown hair disheveled, his oversized glasses flecked with grease—pours Tang from the jar directly into his palm and licks the orange powder. The sugar hits his bloodstream. He can keep going. There is a deadline looming and not a moment to be lost. Earlier, he had told a company that he had exactly the software they needed. The reality was a little different, but the duo eventually delivered. Out of that first piece of code they wrote in 1975 was born Microsoft.

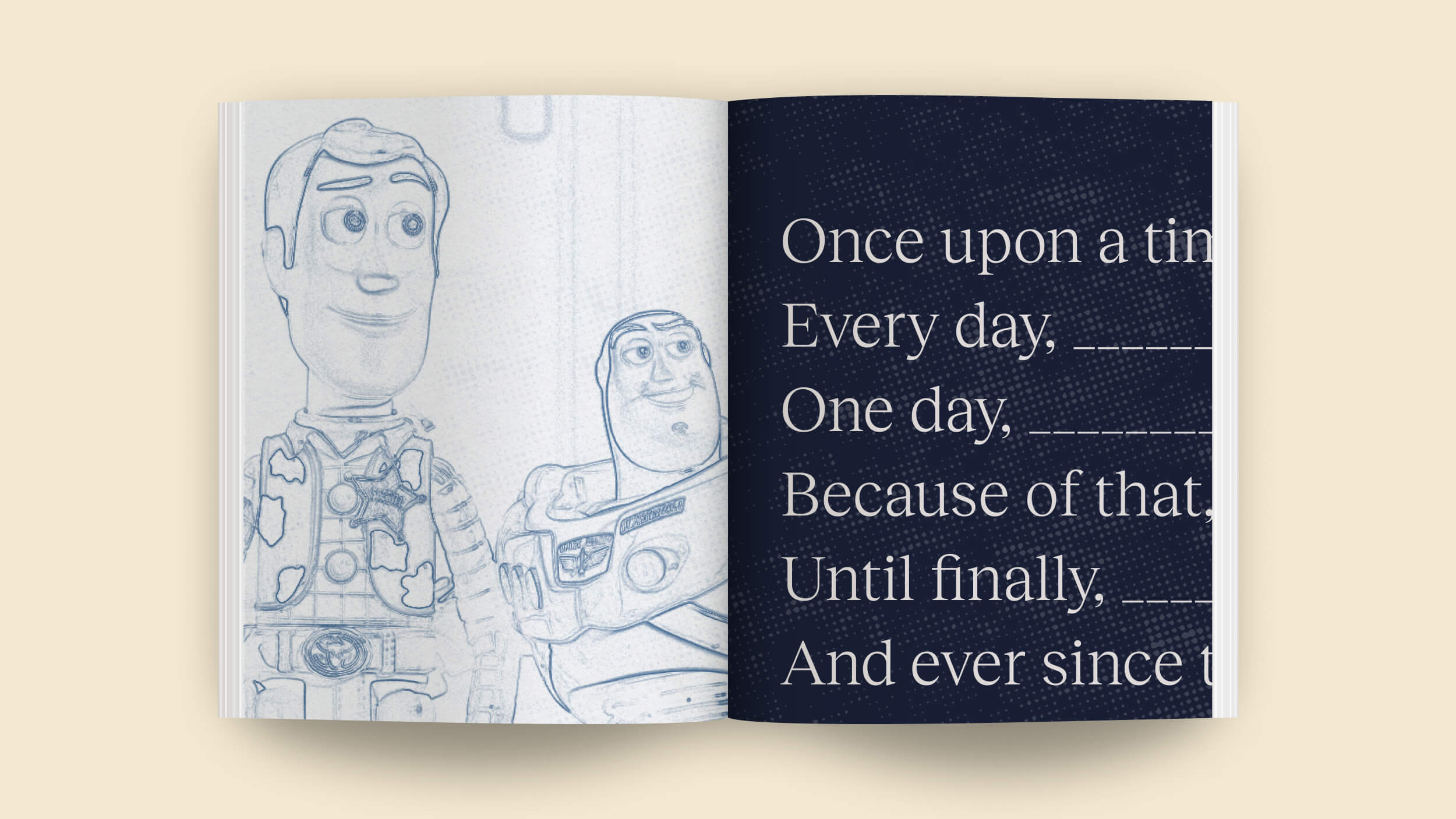

We love origin stories of tech wunderkinds like Bill Gates and Paul Allen, the founders of Microsoft. Tales of sleep-starved young men (almost always men) building the companies of their dreams in dorm rooms and rented garages—fueled by little other than caffeine, drugs, sugar, and an unwavering determination to change the world, and becoming fantastically rich in the process—feed the narrative of American innovation and individual success. In recent decades, with successful entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley and elsewhere producing unicorns and decacorns by the dozen, the “nerd founder” has reached folkloric status. Nerds, with their unruly hair, social ineptitude, and uncanny brilliance, are objects of wonder, parody, and envy, and even worthy of emulation. They inspire both popular culture and academic study. Nerd brains and the fruits they bear have become American capitalism’s greatest asset, creating immense value for society and cementing the country’s top spot in technology.

“The lonely-nerd-turned-accidental-billionaire narrative has assumed the mantle of the Great American Success Story,” the historian Nathan Ensmenger writes in “Beards, Sandals, and Other Signs of Rugged Individualism,” his 2015 paper about how computer professionals of the 1960s and 1970s built a masculine identity around programming. The computer nerd, Ensmenger writes, thus became a “stock character in the repertoire of American popular culture, his defining characteristics (white, male, middle-class, uncomfortable in his body and awkward around women) well established.”

There is perhaps no nerd more representative of the early coalescence of technology, popular culture, and capitalism than Gates, the one with the greasy glasses. Of all the early tech savants, the Microsoft cofounder had serious programming credentials and a deep understanding of technology. But arguably, his biggest victory lay in his business vision. Gates saw a commercial market for software where none existed and built one of the world’s biggest companies based on that vision. A year after Microsoft went public in 1986, Gates became America’s youngest billionaire and the first to make his fortune from technology. He was 31 years old.

He was also an awkward young man who could be imperious and intolerant of others. He chewed so often and so furiously on the stems of his glasses that the plastic ends frayed. The rhythm with which he rocked back and forth in his chair was a barometer of his engagement with a topic. He displayed bouts of frightening intensity and passion, but he was physically unassertive. Software was his primary language. In story after news story and book after book, writers made a point of mentioning his appearance and behavior in the same breath as Microsoft’s latest software. Even the occasional frosting of dandruff on his shoulders became a subject of private discussion among tech reporters. Gates still exhibits some of those tics. He slouches when he stands, slumps when he sits, often gesticulates wildly with his hands when he is animated or tucks them under his armpits when in listening mode. Sometimes, when making a point, his arms stretch as wide as the wings of an osprey in midflight. His feet tap in time to the pace of his speech.

He studs his sentences with words like “neat” and “cool.” Gates once called his rocking and swaying body movements a “metronome” for his brain. Social niceties and small talk meant to lubricate the start of a conversation are lost on him. Repartee isn’t his forte, although people close to him say he has an offbeat charm that comes through in small settings; Buffett told this reporter that Gates has a “keen sense of humor.” Still, it can be excruciating to watch him work the room at a cocktail party, say, in Davos, or at dinner after a conference. As Ken Auletta wrote memorably in World War 3.0, his detailed book about Microsoft’s battle with the government over its monopolistic practices in the late 1990s, a conversation with Gates was “business sex, without the foreplay.”