How a visionary dot-com leader was scorched by hindsight’s afterburn

- During the 90s dot-com bubble, creative entrepreneur Josh Harris had a bold idea: streaming videos online at Pseudo.com.

- Sadly for Harris, the technology and culture were not ready.

- Harris’s story is one of many lessons made clear in hindsight — sometimes being ahead of your time can pave the way for others.

It’s New Year’s Day, 2000, and a line of NYPD officers is primed to raid an underground bunker of armed criminals. Vizors down, body armor tight, and guns ready. Crash. A lock gets broken and splinters fly. A door slams inward and the shouting begins.

“NYPD! On the ground. Get on the ground!”

But this is not a group of terrorists. This is not a cult training for the End Times. This is something much stranger: it’s a group of artists.

Back in the late 1990s, the millionaire son of a CIA agent — Josh Harris — was investing a lot in various alternative art pieces. He was a curious and creative entrepreneur who brought a bit of Warhol to the digital world. He often walked around his Pseudo Programs office dressed as a character he named “Luvvy” — a Halloween clown in smeared makeup. Harris threw debauched, tabloid-grabbing parties in his Soho loft and was a big deal in the New York underground art scene. And, in 1999, he devised his Big Brother-esque pièce de resistance: QUIET. QUIET: We Live in Public involved 150 volunteers living in a bunker, with a dining hall, transparent showers, and cameras everywhere. Over several months, the participants talked, ate, showered, crapped, and had sex, all in the glare of a camera’s tiny red light.

QUIET came to an end not because of consensual voyeurism but because of guns. For some peculiar reason, Harris had insisted on installing a firing range in the QUIET basement and his 150 guests were frequent users. Both the US Justice Department and the people of New York didn’t take kindly to thousands of live rounds fired under their feet. And so, QUIET was shut down.

The story of QUIET is a mirror of Harris’s own life. It’s a story of exhilarating success and creative extravagance followed by poetic downfall. This is the story of Icarian arrogance brought crashing down by naivety, foolishness, and being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

A good idea at the time

Harris made his millions by setting up Pseudo Programs Inc. which was one of the pioneers in “netcasting” radio and video content. Harris founded the company in 1993 by recording his own AM radio show and then distributing it in the nascent internet days. Pseudo.com was Spotify and YouTube before they were even ideas. Part of the early success of Harris’ company was that it was so unconventional. The bacchanalian parties he threw in SoHo were not just some gonzo binge of sex, drugs, and anarchism — they were a recording project. It was only because of his wild Manhattan events that Harris managed to secure such talented and celebrity content creators. Often, he would record the various and intoxicated happenings at his parties to then audio-stream them to his growing online media empire. The Pseudo.com channels were popular and lucrative and went on to define a lot of mid-1990s electronic music and hip-hop.

In the late 1990s, Harris had a different idea: he wanted to focus more on video content. Harris wanted to rationalize the 40 or so radio programs Pseudo ran into eight “channels” which centered much more on their video elements. This was not a polished, studio-shiny kind of production but it was also rather “like watching Oprah.” Harris wanted the world of online video to be a live, gritty, and realistic interaction between humans.

It was a good idea and seemed to align with what had made Pseudo.com such a success so far. And so, with $14 million in his pocket and the collective bureaucratic heft of Intel in his phone book, Harris and Pseudo were set to transform the online world.

Within five years, they were bankrupt.

Jumping too early

It’s hard to imagine (or hard to remember) just how different the early internet days were. Today, websites are bloated audio-visual spectacles and we watch gifs and short-form videos as quickly as it takes to lift a phone. But this has certainly not always been the case.

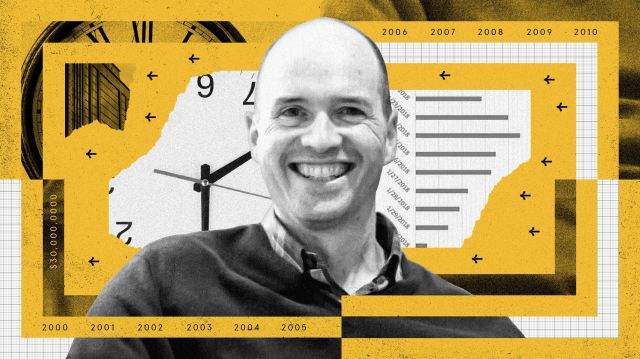

In 1991, the average download speed was just 14.4 kilobits per second (kbit/s). Today, a standard website is roughly 2 MB, so that means it would have taken just under twenty minutes to load the Big Think front page back in 1991. But, the invention of the dial-up modem completely changed that. In 1994, internet speeds doubled to 28.8 kbits/s, and by 1996 — when Harris and Pseudo.com had their idea — speeds were cruising at 56 kbits/s. You can understand Harris’ logic. Internet speeds seemed to be mirroring Moore’s law and were doubling roughly every two years. So, at the turn of the millennium, most people would be able to have fast enough internet to accommodate easy online streaming.

Harris was a highly intelligent and fascinating innovator who had the right idea at the wrong time.

Harris was ready to jump but he jumped too early. Online media companies, then and now, always have a hard time reaching profitability and Harris thought to move from an advertisement-funded model to content syndication. They wanted to produce, paywall, and sell high-quality content. Pseudo.com burned through millions and millions of dollars in trying to get their video content going. They created a lot of original, professional material but the audiences just weren’t there yet. Yes, internet speeds were improving, but the speeds were still not fast enough for it to be a seamless experience. What’s more, the user base was still too small. Not only in terms of modem requirements but in terms of culture.

Today, billions of people watch movies on tablets, Reels on Instagram, and TV shows on YouTube. In the 1990s, traditional broadcast media was king. It would take a lot more time, and many more billions, to rival that. And so, with the millions peeling away, the investors eventually got cold feet. Pseudo.com was another causality of the dot-com bubble bursting.

The timeline of hindsight

The reason why Harris and Pseudo.com make for such a compelling story is that, from our vantage point today, it looks so tragic. Their idea was a good one but they were just too early. It’s like someone climbing Everest but slipping on the final ascent; or someone dying on a desert island a day before help arrives. In the early 2000s, new technologies allowed an increased bandwidth, meaning a speedier and more reliable connection. In 2002, the DVD Forum developed “adaptive bitrate streaming” which allowed much more efficient streaming over websites. Then, in 2005, came the billion-dollar business that could have been Pseudo: YouTube. Justin.tv (later Twitch) and Netflix soon same after and now, here we are, in the streaming age of the internet.

Harris belongs in a lineup of history’s eccentric, but brilliant, innovators. He attracted a loyalty among his workers which, at times, even veered on the cultish. He was a highly intelligent and fascinating innovator who had the right idea at the wrong time.

While Pseudo.com may have collapsed, it laid the groundwork for the digital revolution that came moments after he left. Harris saw a future of digital connectivity and media consumption that was just beyond the horizon — a horizon he and his team wouldn’t reach. His story serves as a reminder that sometimes, being ahead of your time means paving the way for those who come after.