When We All ‘Talk Like TED,’ TED Will Go Mum. Here’s Why.

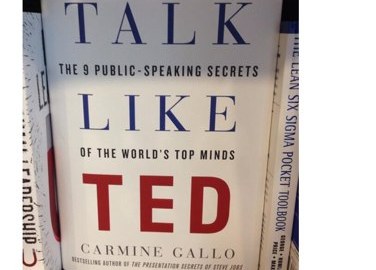

Earlier today the game designer and philosopher Ian Bogost tweeted the above photo, signaling that TEDism—the look and feel of those incisive idea-filled talks from TED conferences—is spreading far and fast beyond its original audience of tech types. Carmine Gallo’s book, which came out a few weeks ago, is pretty high up in the Amazon rankings. A great many people, it seems, want a piece of TED charisma. This leaves me wondering if the TED style might not soon become the balsamic vinegar of public speaking.

Not so long ago, balsamic vinegar was rare, expensive and new to Americans. To want it on your salad was to be sophisticated and in-the-know about food. The costly version, made in the traditional way in the Italian provinces of Modena and Reggio, remains scarce. But mass-produced stuff, which still carries the designation, has spread far and wide. Some 40 percent of the money Americans spend on vinegar in grocery stores pays for balsamic. And in 2012, certifying the vinegar’s transition from class to mass, the Heinz ketchup people added a line of balsamic ketchup.

Nowadays, as you might expect, those who pride themselves on their sophisticated tastes—the kind of people who might have sought our the balsamic in 1973—no longer care (unless they can get the still-rare Modena stuff). I think it’s likely that the TED formula, by spreading wide, will be abandoned by the elite that codified it.

Why? As a general rule, we want the things we eat and drink and read and watch to align with our tastes—that is, to jibe with our sense of ourselves. But how do you obtain this essential knowledge of what befits the type of person you think you are? How do we know that wearing a pork pie hat and drinking martinis is appropriate for a 29-year-old man in 2014? For each of us, there is one guide: the map of humanity inside your head. It’s that map that tells you not to bring an Entenmann’s store-bought pastry to your friend’s all-organic, sugarless, gluten-free brunch. If you should contemplate such a mistake, your mind will note the mismatch between the food and the kind of people who will be judging you when you show up. Taste—your preferences in food, clothes and music, and your knowledge of those preferences—marks where you belong on the map, as clearly as language or skin tone.

Unlike language or skin tone, though, taste is easy to change.

Why would we want to, though? Why, after years of presenting your ideas with the same old Powerpoint, would you suddenly feel frumpy for not being more TED like? Why did it seem imperative a few years back to replace that apple cider vinegar with balsamic?

The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu famously described how people use taste to mark their place in society—by which he meant not only how much money they have but also how much social connection (“social capital”) and mastery of valued knowledge (“cultural capital”). These non-money forms of capital are very important to our place in society and our sense of ourselves. It’s because I have “cultural capital” that I can look down on the vulgarian Donald Trump or the elfin fabulist Jonah Lehrer. They both have more money and social connections than I do, but I can tell myself that I have something they don’t. I wouldn’t wear Trump’s hairpiece or abide by Lehrer’s notions of journalistic rigor. I’ve got taste. (Of course, the effectiveness of this consolation varies with circumstances. There are times when all the good taste and discretion in the world will feel like nothing compared to someone else’s ability to fly first class or sell a book even after disgrace.)

Now, one way to mark that you are a serious person who has earned cultural capital, Bourdieu said, is to prefer things that are harder to find, less easy to enjoy immediately, more difficult to grasp. Would you rather read Pierre Bourdieu than Malcolm Gladwell? Without in any way doubting the sincerity and conviction of your taste, we can say that you’re marking yourself as a member of a cultural elite. Because we are a species that is very sensitive to hierarchy, the gradations many and subtle. While you’re looking down on a Gladwell reader, she might be smugly ignoring a Michael Crichton reader, and so on down.

Now, if Bourdieu should ever become Crichton-popular, so that knowing his work no longer marked you as possessing a taste for the rare and difficult, then his value as a marker of cultural capital will decline. you’ll have a motive to believe that he’s been overblown. Appreciation is not so hard or rare when a product can be found in airport bookstores, or inside some ketchup.

These ups and downs have nothing to do with the inherent value of the items on Fortune’s wheel. Wanting a tattoo was a thuggish taste in North America in 1959; it marked you as cool in 1989; today it’s nothing special. When I was first reading Philip K. Dick his work was dismissed as pulpy trash. Today he is in the Library of America. Valuations change, and when they change an item that once stood for mass market comes to mean “hip”—or vice versa. (Looking at you, normcore.)

Meanwhile, as the meaning of tastes change, so do people. Campus chic may require an eyebrow piercing, but corporate ladder-climbing may impel you more toward a smooth face and an expensive suit.

So while we all want to have good taste, appropriate taste—to feel that our clothes and music and food place us with the right kinds of people—we have a problem. The meaning of the objects we judge keeps changing. So does our own sense of ourselves. No wonder, then, that people are all the time arguing about matters of taste. Why debate with someone who loves that stupid song? Why be upset if your friends hated that movie you loved? Why care? If you and I don’t share the feeling, then either we don’t belong together or, worse yet, we do belong together, which means there’s something wrong with me. Maybe the ne plus ultra of this feeling is the scene in the Tod Browning’s movie Freaks, in which a gaggle of sideshow denizens welcomes their friend’s pretty new bride by chanting “one of us! one of us!”

Don’t get me wrong, I think TED talks are often terrific. TED rules—which I learned when I did this TEDx event a couple of years ago (yes, I am sorta-cool; not TED cool but TEDx cool, about which I feel a status-conscious, anxious pride)—make a good framework for presenting ideas. But if TEDification proceeds and really large numbers of people get in on the act, I am certain that two consequences will follow. First, the cachet of “talking like TED” will vanish. Then, we will hear a lot more about what’s wrong with the TED approach, as social and cultural elites respond to the need to distinguish themselves from the masses. As we have reached “peak balsamic” in the past few years, and as we have, according to these researchers, now hit “peak beard,” so we may be about to hit “peak TED.”

Follow me on Twitter: @davidberreby