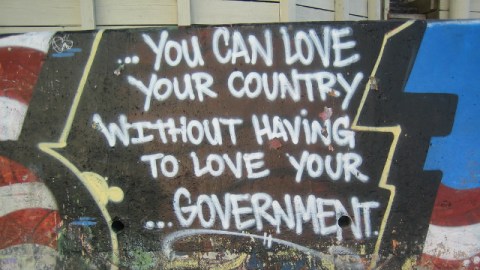

Welcome + The Beautiful Optimism of Libertarianism

Welcome to Action In Action, a new column on Big Think that seeks to investigate and clarify the underlying structural causes of America’s economic, political, and social problems.

Some background on me: I am a playwright and theatre producer in New York City who has been politically active for years. Most recently, I’ve been inspired by and involved in the Occupy Wall Street movement, both ‘on the ground’ and — more often — virtually. I wrote a piece for Big Think called “Occupy Wall Street: A Giant Human Hashtag” that lays out my thoughts on what this ‘movement’ really is: a giant conversation. And I’d like to welcome you to be a part of it.

My first column will focus on a world view I’ve been interested in for years: libertarianism — and, most importantly, what motivates it. I’d love for you to let me know in the comments what you think of my analysis.

—

The Beautiful Optimism of Libertarianism

For years I believed that the underlying ‘flaw’ in the libertarian, free-market mindset was a lack of compassion, a selfishness that permitted one to ignore the suffering and struggles of others. However, I am now starting to believe that libertarianism — at least for those who espouse it honestly — stems from incredible optimism, an unshakable belief in human dignity, honesty, and generosity.

Consider the following article, “Just Ditch Medicare and Medicaid,” by Jacob Hornberger, the founder and president of the Future of Freedom Foundation, an organization whose website says their mission is to “advance freedom by providing an uncompromising moral and economic case for individual liberty, free markets, private property, and limited government.” In arguing for conservatives not to be hypocrites and embrace ending Medicare and Medicaid, Hornberger writes an incredibly revealing passage:

“What about the poor?

Socialism destroys our faith in our fellow man. The poor would be handled voluntarily by doctors, hospitals, and other healthcare providers. They would be making so much money (no more income tax on them too) that most of them would have no reservations about helping those in need as part of their regular medical practice. They’d feel good about it.”

Of course, one can take the cynical, easy view that Hornberger is deliberately misleading his reader for some sort of personal gain — perhaps he and his friends stand to benefit financially and pay fewer taxes by eliminating Medicare and Medicaid, which together account for 21% of the U.S.’s federal budget — but when I look more closely I sense a true optimism underlying this passage, a belief that people will look out for one another best in the absence of government intervention.

I think Hornberger is saying that removing social safety nets such as Medicare and Medicaid would allow individuals — in this case, doctors — the ‘freedom’ to fully realize and act on their own compassion; instead of treating patients merely out of obligation (e.g. emergency room doctors who, since 1986, are bound by law to treat all patients regardless of whether they can pay) doctors could do generous acts and “feel good about it,” since their kind actions would stem from their own personal agency.

Hornberger goes on to say:

“I grew up in Laredo, Texas, which the U.S. government said was the poorest city in the United States in the 1950s. Every day, the doctors’ offices in Laredo would be filled with poor people. There was no Medicare or Medicaid. I never heard of one single doctor turning anyone away because the patient couldn’t pay. Nonetheless, the doctors were among the wealthiest people in town. They used the money that they were making from the middle class to underwrite their providing free health care to the poor.

That’s the way things would be without Medicare and Medicaid. That’s the way things should be. Charity means nothing when it comes out of government force.”

While I can’t verify the legitimacy of Hornberger’s claim that “I never heard of one single doctor turning anyone away because the patient couldn’t pay,” I think the telling sentence here is “charity means nothing when it comes out of government force.” I am beginning to see that, for the faithful libertarian, charity is not a system but a personal choice; from this perspective, for people to achieve their full potential as individuals they must not be obligated by society to help one another (e.g. with government social programs paid for by taxes) but should simply be ‘allowed’ to realize and demonstrate their own generosity and charity.

As Hornberger seems to be suggesting, true libertarianism stems from the belief that people, left to their own devices, will eventually act in a manner that is beneficial to both themselves and to their society. It is this optimism that I find beautiful — this belief in the inherent goodness of others, if only they were given the opportunity to demonstrate it — and this is where I think those who generally look at libertarianism as a cynical, purely selfish world view can begin to engage and at least consider some typically ‘libertarian’ ways of thinking.

Many people — self-described ‘libertarians’ and ‘socialists’ alike — are disenchanted with the hypocrisy and injustice of much of the U.S.’s current political, legal, and corporate landscape, and only by empathizing with one another — trying to understand what motivates others’ views instead of simply dismissing them entirely — can people with seemingly disparate points of view begin to find common goals and work together to achieve them.

Image credit: philosophygeek/flickr.com