Was the “Rise of the Rest” Inevitable?

In a word: no—at least no more than the “great divergence” that preceded it. Some calibration between developed and emerging economies was indeed inevitable, if only because the former couldn’t indefinitely sustain higher rates of growth than the latter. But if, by the rise of the rest, we’re talking about the “great convergence” that began with the emergence of the Asian Tigers, accelerated with explosive growth in China and India, and continues today with numerous other countries spanning the globe—all within the past five decades or so—then it was far from preordained.

In fact, although the scale and speed of that phenomenon may seem to evince its inevitability, what’s striking is how improbable it has been. Take its poster child, China. Given how extraordinary the results of its market-based reforms have been over the past three and a half decades, it’s easy to look back and ask how anyone could’ve—or why anyone would’ve—chosen a different course. And yet, as Ezra Vogel explains in Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2011), China undertook those reforms against immense odds:

Deng faced a tall order, and an unprecedented one: at the time [1978], no other Communist country had succeeded in reforming its economic system and bringing sustained rapid growth, let alone one with one billion people in a state of disorder….[He was] realistic about changes that needed to be made: he knew that the party he had inherited in 1978 was bloated with dead wood and unable to provide the leadership needed for modernization….China did not have the experience, rules, knowledgeable entrepreneurs, or private capital needed to convert suddenly to a market economy….He could not suddenly disband China’s existing state enterprises without causing massive unemployment, a result that would have been politically and socially unsustainable (pp. 3, 475).

Or consider India, the smaller poster child. True, unlike the reforms over which Deng presided, the ones that then-Finance Minister Manmohan Singh introduced in 1991 came in response to a fiscal emergency. That his hand was forced, however, doesn’t diminish the boldness of his proposals, which not only allowed India to avoid defaulting on its debt, but also laid the foundation that has made it into a pillar of today’s global economy.

Of course, the rise of the rest is far more than a “Chindian” story. There are many other developing-world successes that may not have materialized had it not been for prudent policies on the part of their leaders. Four of the most notable transformations have occurred in Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia, and Africa.

Brazil

At last year’s U.S.-Brazil Business Summit, President Obama declared that it “has stepped onto the world stage as a major financial and economic power….Brazil has proved to the world…that participation in the global economy can lead to widespread opportunity at home….[Brazil is] a model for the future.” It achieved energy independence in 2006, became a net external creditor in 2008, and overtook the UK last year to become the world’s sixth-largest economy.

Up until the mid-1990s, however, Brazil was “too much of a mess for anyone to take it seriously on the world stage.” Just one indicator of how bad its economic situation was: inflation there peaked above 6,800% in 1990.

Turkey

Reacting to its 11.4% growth in the first quarter of 2010, The New York Timescalled it “an astonishing transformation for an economy that just 10 years ago had a budget deficit of 16 percent of gross domestic product and inflation of 72 percent.” That transformation is perhaps most clearly reflected in Turkey’s attitude towards the European Union. In December 2002, about three months before he assumed office, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan argued for its inclusion in that organization:

For the adoption of the Turkish model at the global level, it is important that the Turkish desire and will to enter the EU not be frustrated….Turkey has been taking decisive steps in the area of democracy to achieve compatibility with the EU and has achieved significant progress….our first priority is to transform our country into a country of freedoms in accordance with the highest standards in the EU.

Here was Erdoğan at the beginning of 2011: “We are no more a country that would wait at the EU’s door like a docile supplicant….Europe has no real alternative to Turkey….the EU needs Turkey to become an ever stronger, richer, more inclusive, and more secure Union.”

At the turn of the century, however, struggling to contain the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and reeling from a financial crisis in 1994, Turkey’s “regional influence…was almost as feeble as its economy.”

Indonesia

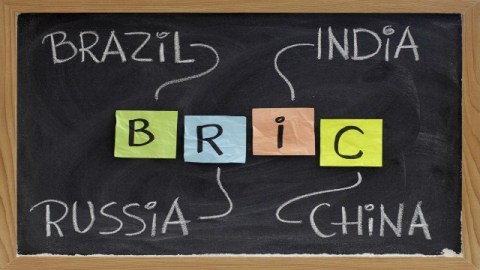

It has made considerable progress reining in Islamic extremism and bringing down its budget deficit to a sustainable level. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton has labeled it one “of the [two] most dynamic and significant democratic powers of Asia,” India being the other. Those two, she continued, are “key drivers of the global economy, important partners for the United States, and increasingly central contributors to peace and security in the [Asia-Pacific] region.” Indonesia’s economic performance in recent years has even compelled some observers to recommend that BRIC be replaced by BRIIC.

Not even a decade ago, however, it was “an economic and political basket case, riddled with graft…Its heavily export-dependent economy collapsed in the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, plunging the country into political chaos….[Following the 2002 bombing in Bali that killed over 200 people,] Indonesia seemed on the verge of disintegrating, torn apart by separatist movements and inter-ethnic battles.”

Africa

Calling it “ripe for reappraisal,” the Financial Timesobserved that

[t]he perception that Africa has reached a turning point—one qualitatively different from previous false dawns—stems from a combination of global and regional circumstance….Growth has been spurred by market liberalisation and improved public management of finances as well as a boom in the commodities that Africa has in abundance. Perhaps the biggest factor has been the engagement of emerging powers…led by China….But the story is no longer just about resources. The commodity price surge has coincided with the rapid expansion of banking, telecommunications and other services formerly weighed down by the dead hand of the state.

When one considers how long Africa has been seen as condemned to poverty and warfare, almost as if in accordance with some unwritten law of geopolitics, this reassessment of the continent’s prospects is among the most remarkable stories of our time.

One can easily imagine how these four (unfinished and reversible) success stories could’ve been tales of stagnation, even regression. On the flip side, countries such as Zimbabwe and North Korea are reminders that even countries with great promise can quickly bring crushing impoverishment and isolation upon themselves.

The bottom line: Outcomes aren’t preordained. If it’s misguided to focus too much on short-term fluctuations at the expense of the bigger picture, it’s also mistaken to see overarching trends as a policy straightjacket. While they certainly impose constraints, they leave plenty of room in which creative pragmatists can operate.

Follow Ali Wyne on Twitter and Facebook.

Photo Credit: marekuliasz/Shuttershock.com